© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

21st-Century Choreographers: Symphonic Dances, Pictures at an Exhibition, This Bitter Earth, Everywhere We Go

Washington, Kennedy Center Opera House

8 April 2015

www.nycballet.com

www.kennedy-center.org

Only three years ago, New York City Ballet soloist Justin Peck was virtually unknown. Today he is NYCB’s resident choreographer and the hottest young dance-maker in this country – an artist known far beyond the world of ballet, thanks in no small part to the recently-released documentary, Ballet 422, which offers behind-the-scene glimpses of his craft.

So far I have seen three of his works: Year of the Rabbit (2012), his first major choreographic success, Rōdē,ō: Four Dance Episodes (2015), his brand new piece for the company that premiered this winter and Everywhere We Go (2014), his repeat collaboration with indie musician Sufjan Stevens. The latter was presented as part of the second program, called 21st-Century Choreographers, of the NYCB spring sojourn at the Kennedy Center Opera House in April.

All three works demonstrate Peck’s undeniable choreographic gift and have one common trait – they are whimsical reflections on ordinary life. All three have no plot, but their imagery suggests human relationships and personal stories – our stories – told from the point of view of a young person, imaginatively and wittily, without pompousness or pretense. In all three, Peck is at his best with ensemble choreography, which he conjures with the eye and imagination of a savvy architect. Innovative and never predictable, his patterns and formations for large groups of dancers are as eye-catching as they are utterly memorable. Their imprints linger in memory long after the performance is over.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Everywhere We Go, which concluded the 21st-Century Choreographers program, is a large-scale, elaborately-conceived piece with a cast of 25 dancers and commissioned music by Stevens. (For Year of the Rabbit, Peck used the composer’s preexisting music; for this ballet, the score was created from scratch.)

Everywhere We Go is outfitted with chic and a smile by Janie Taylor, former principal ballerina of the company. Dressed in white tights and sailorette tops, the women look playfully modish. The men, in black-and-grey outfits, look sharp and formal, yet still very stylish.

Karl Jensen’s geometric backdrop dances with music and light. Its shapes expand and contract, aptly underscoring the surges of the music and the happenings onstage. In its musical texture, the nine-movement score has a minimalist vibe to it. Propulsive and pulsating, the music runs and rolls with infectious brio, its rhythms punctuated by serious brass and pounding piano. At times, however, the score’s dynamics and musical ideas crumple or come to a halt altogether, as if the composer allows the dancers – and the audience – to take a breather. In these rare moments, regrettably, the choreography also takes a nose-dive.

The ballet opens with three male duos, in which one man with his hand shields the eyes of his partner from behind. When the music starts they burst into an invigorating dance. At one point, as if to further reflect on the title of the first movement, “The Shadow Will Fall Behind,” in each duet one man stands on his feet while the other, in sync, repeats his movements lying on the floor, his feet firmly pressed against his partner’s. I call this clever and witty section “three men and their dancing shadows.”

Peck lets his dancers luxuriate and have utter fun with his steps. For the most part, the piece evokes a joyful spring-day parade; yet, now and then, the happy atmosphere is overshadowed by episodes of misfortune and sadness. The intricate lines and configurations form and dissolve, the group formations rise and collapse, the solo dancers materialize only to disappear from view, being swept away from the stage by an all-consuming tide of the ensemble. It’s all immensely exciting to watch and, I am sure, to dance.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The opening night performance featured an outstanding group of dancers in the leads: Sterling Hyltin, Maria Kowroski, Tiler Peck, Andrew Veyette, Russell Janzen, Amar Ramasar and Teresa Reichlen, most of whom originated their roles when the ballet premiered in 2014. All of them are exceptional artists; and all brought to their parts not only their prodigious technique but also their distinctive personalities, greatly enhancing the overall perception of the work.

Also on the bill was Alexei Ratmansky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (2014), his new ballet for NYCB. In it, the cast of 10 dancers (five women and five men) ingeniously animate the piano score by Modest Mussorgsky which gives the ballet its title. Composed as a collection of vivid miniatures, the music is rightly regarded as a masterpiece of the classical piano repertory. Ratmansky imbues each of the ballet’s sections (16 in total) with its own character; and his choreography, playful in tone and theatrical in nature, translates the moods of the music in an utmost ingenious and unpredictable fashion.

In the opening Promenade, the entire cast assembles onstage for what appears to be an impromptu concert in which the dancers are both spectators and participants, each taking center stage in a brief solo, while others attentively watch the performance from their “seats in the audience.” Sara Mearns brought out her forceful, untamed side in The Gnome, her movements intentionally ungraceful and rough but imminently captivating. In contrast, the lissome Sterling Hyltin and Tyler Angle danced with lovely suppleness in a mesmerizing duet in “The Old Castle.” In “Bydlo,” Hyltin and Mearns, together with Gretchen Smith and Indiana Woodward, evoked a quartet of conspiring witches, their backs hunched and gestures grotesque. As they danced it seemed as if their characters were indeed concocting something suspicious and nasty, especially when, at the end, they tiptoed off the stage with amusingly exaggerated fear. Angle, Adrian Danchig-Waring, Gonzalo Garcia, Joseph Gordon and Amar Ramasar were all cheeky in “The Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks.” Ramasar delivered his vigorous solo in “Baba Yaga” with intense, rowdy flair; and his following duet with Mearns was as fierce and ominous as the music’s title character, Baba Yaga – a famous bad-tempered witch of Russian folklore. The entire cast joined forces in the ballet’s festive conclusion set to the celebratory sounds of “The Great Gate of Kiev.” Pianist Cameron Grant gave a top-notch performance of Mussorgsky’s score.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

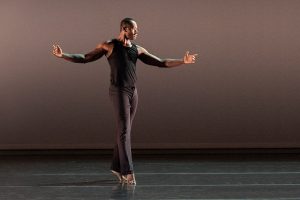

Christopher Wheeldon’s evanescent and sleek duet, This Bitter Earth, accompanied by Max Richter’s arrangement of Dinah Washington’s song, received a soulful treatment from Tiler Peck and Craig Hall. Equally regal and serene, the dancers illuminated the emotional landscape of the piece with their gorgeous, exquisitely-nuanced performance.

The program opened with Peter Martins’ Symphonic Dances (1994) – a strangely antiquated take on a Russian theme, inspired by Sergei Rachmaninoff’s orchestral music of the same title composed in 1940. It’s a big, expansive dance for a principal couple, four soloist couples and an ensemble of 16, all clad in stylized Russian folk costumes of various shades of green and beige. On the surface, the choreography looks handsome, but deep down, the ballets conveys little meaning. There is no drama and, consequently, no resolution.

On opening night, however, the excellent cast transcended the material and often made this Dances soar. I particularly enjoyed the incomparable Teresa Reichlen in the principal ballerina role. Blessedly, she was given some of the best choreographic lines in the entire ballet. She was partnered with gallantry and confidence by the superb Zachary Catazaro.

You must be logged in to post a comment.