© Cristian Lazarescu. (Click image for larger version)

Bucharest National Ballet

29: Classical Symphony, Petite Mort, Marguerite and Armand

30: Tango, Radio and Juliet

Bucharest, Opera House

29, 30 April 2015

www.operanb.ro

The Opera House in Bucharest deceives to flatter. It stands on an unprepossessing and detached site at the end of a long boulevard, close to the Ceauşescu Palace in the Cotroceni neighbourhood of Romania’s capital city. Classical features dominate impressive external architecture, flaunting a fascinating series of bas reliefs on the façade and a commanding arcade of three long, thin arches leading into a portico.

This imposing edifice’s grandeur continues into the building. An intimate circular auditorium, having a surprisingly small audience capacity of around 950, is surrounded by distinctly opulent and palatial public areas, criss-crossed by sweeping staircases, laid with red carpets, and featuring sumptuous gilding; patterned marble floors; internal columns and arches; huge, luxuriously-panelled double doors; and painted ceilings graced by majestic chandeliers.

© Cristian Lazarescu. (Click image for larger version)

This glorious jewel of a building has been recently renovated and it appears, as any other grand nineteenth century opera house, fit for kings and emperors. That is, until one discovers that it was opened, just 60 years’ ago – in 1954 – replacing the National Theatre, which had been flattened during the Second World War. It was, in fact, the first major public building of a Romania that had been forcibly turned to communism and – in an ironic twist – the fashionable tastes of this proud nation’s new soviet masters led to this homage to classicism through the mandated architectural style of socialist realism.

The ballet company within has also undergone a major refurbishment under the inspired new leadership of Johan Kobborg, the former Royal Ballet principal who was appointed as artistic director in January 2014, immediately after successfully mounting his production of August Bournonville’s La Sylphide, in Bucharest. In just a year, it would appear that Kobborg has effected a momentous transformation on the fabric, the repertoire and the personnel of a company that was originally formed in 1924.

The health and welfare of dancers tops Kobborg’s priorities and so the spacious studios and theatre stage now have new sprung floors – where there were none before – and there are facilities for physiotherapy amongst other changes designed to improve care for dancers’ minds and bodies. A new generation of performers is also quickly taking shape and they are not waiting for opportunities: Kobborg cast seven young dancers to debut as either Lise or Colas in his recent acquisition of La Fille mal gardée.

© Cristian Lazarescu. (Click image for larger version)

The first of five one-act ballets I encountered on this flying two-day visit to the company could have been a metaphor for the opera house itself, since Yuri Possokhov’s Classical Symphony is also a modern marriage of power and classicism. His personal homage to the ballet pedagogue, Pyotr Pestov (the teacher of both Possokhov and Alexei Ratmansky) is a challenging test for any company. Created in 2010 for the former Bolshoi dancer’s adopted home at San Francisco Ballet (where Possokhov has been based since 1993), it is an exhilarating, accelerating tour through the classical idiom punctuated by very modern accents; a theme that is enshrined in Sandra Woodall’s futuristic interpretation of tutus; stripped-down and pastel-coloured.

Possokhov’s ballet is both conventional and unorthodox, often at the same time, mirroring in many ways the wit and invention of Prokofiev’s brief First Symphony – also generally known as the Classical Symphony – which marries the classical ideals of Haydn with the modern compositional practices of the early twentieth century. It is the perfect director’s pick for these exuberant young dancers, showcasing their capacity for ebullient, if not exhausting, fun. The whole ensemble of fourteen fizzed and twirled through the allegro sections and finale, combining fast, skipping feet with hyper-flexibility in their upper bodies. The two lead couples – petite, feisty Cristina Dijmaru and Robert Enache plus the mellifluous pairing of Marina Minoiu and Shuhei Yoshida – caught my eye with their combination of athleticism, rhythm, expression and robust, all-around, technique.

© Cristian Lazarescu. (Click image for larger version)

Jiří Kylián’s Petite Mort was also a great choice, both in terms of following Classical Symphony and as another exciting challenge for these dancers. Made as a celebration of Mozart to commemorate the second centenary of the composer’s death (in 1991), it is a ballet that simply doesn’t age. Petite Mort has become the Kylián of choice for companies new to this great choreographer’s work: this is the fourth time that I’ve seen it performed by a different company in the last year alone. And, to their credit, these young ONB dancers acquitted themselves at least as well in this sternest of tests in what may be a futuristic take on the wedding night of six brides for six brothers, complete with fencing foils, a huge canopy and wheelie-dresses. Although one of the swords decided to go AWOL (cleverly collected “en passant” by one of the guys), the twelve dancers successfully accomplished the many technical challenges of manipulation and deceit set by Kylián and his repetiteur, Elke Schepers.

It’s a ballet of such ingenious wit, integrating all the elements (including Joke Visser’s sexy baroque-styled underwear and Kylián’s own lighting designs) into a subtle, sensual symbolism that rides the waves of Mozart’s piano concertos with percipient musicality. Dijmaru was once again well to the fore (this time partnering Bogdan Cănilă) as was Kobborg’s recent recruit from the Royal Ballet School, Barnaby Bishop (dancing with Bianca Stoicheciu).

© Cristian Lazarescu. (Click image for larger version)

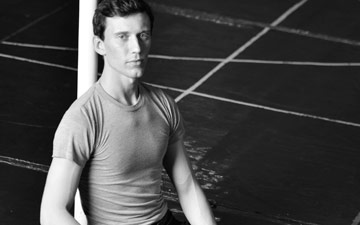

Another of the guys in Petite Mort was also formerly connected with the Royal Ballet. Dawid Trzensimiech swapped his relatively comfortable existence as a soloist in Covent Garden to join Kobborg in Bucharest, within a month of the latter’s appointment. I have no doubt that it was a risky but ultimately very rewarding gamble. The last time I saw Trzensimiech in Marguerite and Armand he was either one of the many gentlemen paying court to Tamara Rojo’s Marguerite or one of the servants at the back. He wasn’t exactly “carrying a spear” but his impact and involvement was much the same.

Now, here he is sharing the title roles in Sir Frederick Ashton’s great one-act narrative ballet, danced exclusively by Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev from 1963 until their deaths (and then not revived until Sylvie Guillem was allowed to take on Fonteyn’s role, in 2000). I can safely say that the role of Armand fits Trzensimiech rather better than it did Nureyev (certainly from filmed evidence). Trzensimiech’s long, elegant legs stretch out forever into yearning arabesques and he danced Armand’s opening solo so well that one can only wonder in happy expectation as to how good his Des Grieux might be; more of which anon.

© Cristian Lazarescu. (Click image for larger version)

Looking around the various men loitering in the background, one wonders how many might make the same progression to top billing by following in Trzensimiech’s footsteps. The one thing they can be sure of is that they have a director who will reward anyone who merits the opportunity.

As to the role so protected for Fonteyn and subsequently Guillem, the latest incumbent was Bianca Fota, a homegrown Romanian dancer who is clearly blossoming into a sublime and disciplined prima ballerina. Her interpretation of the tragic Lady of the Camellias was both meaningful and notably mature with a touching emotional connection to Trzensimiech’s Armand. There were also commanding character debuts by Antonel Oprescu as Armand’s father and Călin Rădulescu as the Duke.

So, my assessment of this first triple bill was of a company that could wear borrowed clothes with style. Three very different, proven, winning ballets were performed with distinction throughout the cast. As with the errant foil, not all went without a hitch and there were some moments in both Classical Symphony and Petite Mort where an occasional lack of unity was evident in the synchronised movement but it made not a jot of difference to my enjoyment of dancers who put their all into the performance. When one considers that these were effectively three company premieres – all new to the ONB repertoire – then this mixed programme was a considerable undertaking, achieved with outstanding professionalism.

30 April 2015

The company wore its own clothes on the following night, returning to home territory with a double bill of work completely new to me in Edward Clug’s Tango and Radio and Juliet. The company has been performing this pair since well before Kobborg’s time and the style suits them. Clug is a Romanian-born choreographer, now settled in Slovenia as director of the Maribor Ballet, for whom both these pieces were originally made. I believe that I’ve seen only one of his works previously – the stunning and highly individualistic interpretation of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring – and it is clear that he’s a choreographer with an original and Herculean vision. Tango was his first ballet, made in 1998, when Clug was just 22 years old. It is a remarkable creation from one so young.

© Bucharest National Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Tango features the familiar, flowing bandoneon music of Ástor Pantaleón Piazzolla – one of the giants behind the development of nuevo tango – and of the French-Argentine singer/composer, Carlos Gardel, amongst others. But, it also possesses a refreshing, almost counter-intuitive, evocation of a more contemporary tango flavour, as evidenced by the Balkan-infused gypsy melodies of Goran Bregović, the quirky electronic influences of Jean-Marc Zelwer and the dominant theme of Cirque du Soleil’s Alegría by René Dupéré. Here is an eclectic, romantic score that underpins a distinguished work, not least because Clug’s choreography is similarly catholic, articulated through a series of diverse duets and group dances, all punctuated by impactful tableaux and highly expressive performances.

Leading this hour-long marathon of frenetic energy was a strong, sensual performance by Adina Tudor as the tragic heroine of the Blind Tango; divinely gorgeous in a red shift dress, especially during a critical mime sequence, “speaking” with her eyes while interpreting the equally beautiful song Querer from Alegría. It was singularly worth the trip to Bucharest.

She was well-matched, both expressively and as a dance partner, by Cănilă who brought a lusty physicality to his role alongside her. For no particularly logical reason, his long solo reminded me of the male variation in Roland Petit’s L’Arlésienne. He also reminded me of the former Royal ballet dancer, Martin Harvey (and, similarly, has all the attributes required of a Lescaut).

Minoiu and Enache invested humour and passion to the Tango Fatal and the harmonious interaction of Diana Tudor (no relation) and Christian Preda as the timid tango pair was superb (I loved the electric energy in the fluid sequence where the nervous duo feel inadequate against the six women seated on a bench next to them).

© Bucharest National Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

If Clug’s Tango took an unexpected journey then his Radio and Juliet was off the radar. Also an hour long, his modernised interpretation of Shakespeare’s tragedy – made in 2005 – is courageously set to the music of Radiohead, hence the title, although it is often punctuated by silence and grainy black & white film. The whole affair is seen through the eyes of Juliet as evidenced by the overlong opening film sequence of her waking up; and it is subsequently set against her interactions with six men in suits. Fota returns as Clug’s surprisingly passionless Juliet; although nonetheless superb in her delivery of his wrenching, mechanistic movement.

Clug’s later choreography is quirky, angular and always active, dictated by the compulsion to make a movement on every beat. His work is filmic, not just because it embraces film, but also because it seems to explore unseen horizontal axes across the stage, as if there are only two dimensions and no depth. The six men are not obviously identified (as Romeo, Mercutio, Tybalt etc) but there are well-constructed fight scenes and at least two deaths, concluding with (one assumes) that of Romeo. Juliet, however, appears to survive and it would seem that the whole narrative exists as flashbacks in her mind while (again, on film) she takes a bath, fully clothed.

© Bucharest National Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Radio and Juliet is one of those works that definitely requires to be seen again so as to appreciate the many nuances and associations, cross-referenced with the Radiohead score (not my favourite) and the film (by Janja Glogovac and Antonel Oprescu), which was easily the most overdone of the elements.

So, in summary, my brief trip to Bucharest led to the discovery of not only a wonderful opera house – perhaps unique in its socialist realism architecture – but a thriving, enthusiastic and extremely talented national ballet company, of which Romania can be justly proud.

Kobborg has inherited some great young dancers who have clearly reacted to his inclusive leadership with an eager commitment; and he has fast-tracked the careers of Trzensimiech (who tells me that he was on the verge of quitting ballet altogether before his arrival in Bucharest) and Bishop. Where to next? Well, Kobborg’s own production of Giselle (made with Ethan Stiefel) is on the immediate horizon. And, I’d love to see this company tackle Manon, which ought to be a future acquisition (no-one knows it better than Kobborg) since every role has a number of obvious claimants in this exciting, young company. For sure, wild Romanian horses wouldn’t keep me away from that opening night!

You must be logged in to post a comment.