© Dave Morgan, by kind permission of the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The Royal Ballet

26: The Dream, Song of the Earth

27: Infra, The Age of Anxiety, Divertissements: Le Train Bleu solo, Voices of Spring pdd, Aeternum pdd, Carousel excerpt

New York, David H. Koch Theater

26, 27 June 2015

www.roh.org.uk

Mixed Rep

On paper it sounded like a good idea: a British company, The Royal Ballet, bringing two evenings of works by British choreographers. The first program, containing Frederick Ashton’s The Dream and Kenneth MacMillan’s Song of the Earth, worked well. Not so the second, which I caught on the evening of June 27. These combined the showily acrobatic (Wayne McGregor’s Infra, from 2008), the ambitious but muddled (Liam Scarlett’s Age of Anxiety), and the inconsequential (most of the short excerpts in the “divertissements” section of the evening).

© Bill Cooper, by kind permission of the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

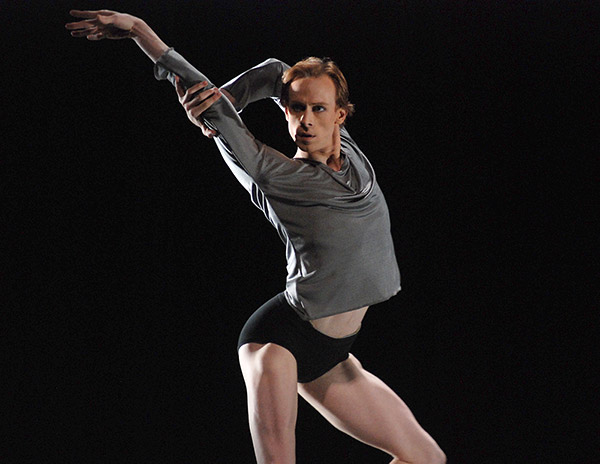

It’s a shame, because dancers like Marianela Nuñez, Natalia Osipova, Ryoichi Hirano and Lauren Cuthbertson are worth watching in almost any ballet, but their talents seem wasted in Infra, a work more dependent on flexibility and extreme technique than on finesse, musicality, or dramatic intelligence. Set to a sentimental and repetitive score by Max Richter (mostly for piano and strings), the work features six couples, moving in hyper-extended backbends and twists, flicks, and undulations, for what feels like a very long time. The lighting is stark; the palette is mostly black and gray. The white-ish overhead lighting tends to foreshorten the dancers’ legs and create unflattering shadows on their torsos. (It also chisels every muscle, useful when the men are bare-chested.) The women are pulled, twisted, and folded into strange and sometimes alarming shapes, their legs held to their heads or pushed toward their groins. Their partners tend to stand behind them, the better to exhibit them to the audience. The sideways split is ubiquitous. Meanwhile, the pace and phrasing of the steps remains almost constant.

According to a note in the program, the work is “an arresting study of life beneath the surface of the city.” What a city! An electronic panel above the stage shows a never-ending stream of digital figures walking, walking. Below, a woman (Lauren Cuthbertson) cries, alone. Another dancer (Edward Watson) pulls at his shirt, twitches. But the emotions feel empty, unmotivated, pasted on. Infra is not much different from other Wayne McGregor ballets I’ve seen. If you tend to enjoy his work, you’ll like Infra.

This was followed by a series of solos and bits from longer ballets. The high point was Vadim Muntagirov’s short turn in the “Beau Gosse” solo from Nijinska’s 1924 ballet Le Train Bleu. Stylish, witty, athletic, and short, it captured the tongue-in-cheek spirit and art-deco style of its time. (The ballet was about bright young things frolicking on the beach at Deauville.) Muntagirov polished off its many challenges with ease. Ashton’s Voices of Spring, a charming pas de deux set to Johann Strauss II, looked rather forlorn on the vast stage of the Koch Theatre; the performance by Yuhui Choe and Alexander Campbell was technically impressive but lacked sparkle. Two men performed solos created for them by dancers in the company, neither original nor particularly memorable. A pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s longer Aeternum, set to a section of Benjamin Britten’s Sinfonia da requiem, was danced by Marianela Nuñez and Federico Bonelli. It had a smoldering mystery about it, but relied too heavily on the oppressive pushing-and-pulling of the woman by her partner. Perhaps the duet makes better sense in the context of the full work. Another excerpt, from Kenneth MacMillan’s choreography for a 1992 staging of the musical Carousel, was notable mainly as a showcase for Carlos Acosta’s scissor kicks, double air turns, and still-significant sex appeal.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013. (Click image for larger version)

By far the most intriguing work of the night was Liam Scarlett’s The Age of Anxiety, based on W. H. Auden’s 1947 reflection on mid-century malaise. The music was Leonard Bernstein’s second symphony, also inspired by Auden. It’s an ambitious and sprawling symphony, jazzy and romantic, and not easy to choreograph – Robbins tried, unsuccessfully, in 1950. Scarlett’s ballet has a story of sorts, concerning four strangers who come together in a New York bar during the Second World War. They flirt, drink, talk, hash out their fears, hide their loneliness. The lone woman (Laura Morera) desires the young sailor (Steven McRae), who aggressively seduces her while simultaneously toying with the affections of a retiring young man (Tristan Dyer). An older gentleman (Bennet Gartside), disappointed with life, hovers on the periphery of their interactions.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

There are strong echoes of Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free in the setting and the music. Four souls lost in the New York night. As in that ballet, the characters establish their personalities through danced monologues, duets, and ensembles. The quartet of dancers is well-assorted. Each has a distinct quality, a color. The suggestions of sexual ambiguity are intriguing. But Scarlett doesn’t have Robbins’ knack for making sense of the dancers’ stories through dance. As the ballet proceeds, it becomes more and more difficult to follow the characters’ train of thought. The ballet loses its way in digression after digression. Still, I was touched by a moment in which the four characters stood together, staring out of a window, each desiring at least one of the others but destined to finish the night alone. Scarlett’s ballet has feeling and imagination but lacks coherence.

© ROH, 2014. Photographed by Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

The night before (June 26), the company had presented its blue-chip double-bill consisting of Ashton’s The Dream and Kenneth MacMillan’s Song of the Earth (reviewed earlier). New casts subtly altered the chemistry of each work. In The Dream, on the 24th, Sarah Lamb’s Titania was fine-grained and restrained; on the 26th Natalia Osipova was a tourbillon of activity. Head tilted back, nose pointed upward with a mix of petulance and imperiousness, she looked and behaved like a character out of a children’s book. Every inch of her body moved, often at once. She quivered at the sight of Bottom, clutching his donkey-ears to her breast with sensual delight, then hopped on his back, and, with a bossy gesture, ordered him to “ride on!” In the final pas de deux with Oberon, she bent and pulled, quivered and twisted with such energy that the tall, handsome Matthew Golding could barely contain her. Like Titania, Osipova is a handful.

© 2014 Royal Opera House / Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

Golding, in turn, brought a welcome weight and darkness to the character of Oberon, as well as a strong legato and stretch to the many arabesques that fill the role. His pas de deux with Osipova was a crescendo of reconciliation. Forgiveness melted into conjugal passion, culminating in fishtail lifts – Giselle gone wild – splits to the floor, and finally, a rapturous swoon across Oberon’s knee. Marital spat resolved.

As we’ve seen in roles like Kitri in Don Quixote, Osipova’s vitality is astonishing; channeled into a smaller, more intimate work like The Dream, it’s even more exciting. The human lovers were rather pallid in comparison, but Jonathan Howells’ Bottom, like Bennet Gartside’s, managed to be funny and touching in equal measure. The corps of fairies, amazingly alike in size and timing, was a delight. Valentino Zucchetti flitted across the stage as Puck, happily vaulting into splits and bent-legged shapes; still, part of me yearned for Herman Cornejo’s stranger, more creaturely take on the role, for American Ballet Theatre.

© 2014 Royal Opera House / Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

A second helping of Song of the Earth revealed deeper connections between images in Kenneth MacMillan’s choreography and the Chinese poems upon which the work is based. But the overall impression was the same: as visual poetry, the ballet often works, but as choreography, it’s frustratingly static. (The self-consciously Asian touches – flexed feet, tilted heads, shuffling steps – are often grating.) The dancing fails to hold its own against the Romantic lushness and rich orchestral palette of Mahler’s songs.

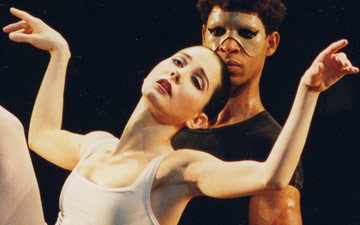

The heart of the piece lies in the second and sixth songs. In both, the central character, a woman in white, is partnered by a masked figure in black, representing death. In the first, she falls, quite unexpectedly, from a standing position on pointe (in profile), to the floor, in one beat. Executed plainly and without the slightest dramatization, it is a powerful image. Both Marianela Nuñez (on June 24) and Lauren Cuthbertson (on June 26) approached this moment, and the entirety of the role, with great simplicity. Their plainness made them all the more affecting. Cuthbertson’s long, strong legs and pale girlish face left a particularly strong impression.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The sixth (and final) song is the most complex and haunting. The woman in white dances with a man, also in white; their pas de deux is jerky and stiff, punctuated with falls and lifts. It is a song of leave-taking, “Der Abschied,” or the farewell. The woman’s body looks inert. The man is given little to no personality by MacMillan: he’s a blank, an ideal or perhaps an everyman. At this performance Ryochi Hirano – handsome, strong, quietly present – did what he could with the part, offering a clean, elegant performance. Later, the two lovers are joined by Death; the woman is pulled and twisted between them until, finally, Death imposes himself, locking the man in a stiff embrace, covering his eyes. (Another resonant image.) On the 24th, Carlos Acosta was authoritative and imposing; on the 26th, Edward Watson imbued the role with a creepy eroticism. Watson’s limbs are tapered and long; he used them to bend the lovers to his will, enveloping them like a spider or a snake.

These are dancers worth following in a wide repertory of works; it’s a shame to see them go while feeling we’ve barely gotten to know them better. The second program, especially, felt like a lost opportunity. Let’s hope they come back soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.