© Kiyonori Hasegawa. (Click image for larger version)

Bejart Ballet Lausanne & The Tokyo Ballet

The Ninth Symphony

Monte-Carlo, Salle Prince Pierre – Grimaldi Forum

3 July 2015

www.bejart.ch

www.thetokyoballet.com

www.grimaldiforum.com

Maurice Béjart’s ballet to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony was created in 1964 and following three years of preparations a 50-year anniversary season of performances commenced last year in Tokyo with the Tokyo Ballet collaborating with the Béjart Ballet Lausanne. The two ballet companies performed the work in Tokyo and subsequently in Lausanne to a total of 35,000 spectators and now, accompanied by the Philharmonic Orchestra of Monte-Carlo and the Monte-Carlo Opera chorus and soloists, 250 people in all, have just given 3 sold-out performances in Monte-Carlo.

© Kiyonori Hasegawa. (Click image for larger version)

In 1959 Béjart had moved his small company, Ballet-Théatre de Paris, to Brussels at the invitation of the director of the Théatre Royal de la Monnaie, Maurice Huisman. The success of his production of Le Sacre du Printemps led Huisman to offer Béjart and his company a permanent home in Brussels, an offer which was immediately accepted. Huisman was eager to make ballet more popular in Belgium and felt the need to move out of the restrictions of the small, old-fashioned stage of the Monnaie. The newly-formed Ballet of the 20th Century moved into the city’s ‘Royal Circus’ building and for certain seasons into a circus tent in the ‘Grande Place’ in the centre of Brussels. Béjart, now with a much bigger company, responded by creating works on a large scale, popular works which established the company’s reputation, not only in Belgium but on world-wide tours. If Béjart and the company were often received critically in London and New York, they were virtually idolised in Europe. Indisputably they attracted new audiences for dance, offered a viable alternative to traditional classical ballet and established the role of the male dancer as equal to the ballerina.

Following Bolero, also an immediate popular success, Béjart choreographed The 9th Symphony, his first full-length production, and by 1964 he had collected a number of the dancers, including Paolo Bortoluzzi, Tania Bari, Duska Sifnios, Jorge Lefevre and Germinal Cassado, who were to become an integral part of the company and of his future creations. Béjart writes in his autobiography that he was “filled with happiness” to translate Beethoven’s music into movement with such a perfect cast of dancers, and that “he took Beethoven’s hand and let himself be guided”. The ballet was a huge success and the company set off on tour for two years, performing in Paris in the immense Palais des Sports and in similar venues in countries as far afield as Russia and Japan.

© Kiyonori Hasegawa. (Click image for larger version)

Although the ballet was planned purely as an interpretation of Beethoven’s music, Béjart added texts from Nietzsche, Schiller and others to the programme notes. These texts underline the major theme of universal brotherhood, a union of races and peoples culminating with the 4th movement’s ‘Ode to Joy’ and that “All men become brothers”. The ballet opens with a typical Béjartian theatrical touch – Gil Roman, now director of Béjart Ballet Lausanne, and the conductor stand centre stage facing each other as the orchestra seated behind them tunes up.

In the dimly-lit area behind them are rows of the chorus, all dressed in muddy brown colours. On each side of the stage is a high platform with, on the right, a set of African drums and a drummer and on the left a conventional percussion set with a drummer. Gil Roman turns to face the audience and walking slowly forward recites a text by Nietzsche with many references to “God”, “man” and “dance”. The African percussionist bursts out playing his drums, followed by more text, the other drummer intervening and finally both sets of drums are played. This is saved from appearing pretentious by Gil Roman’s relaxed delivery and natural stage presence. The first dancer enters, followed slowly by others, all dressed in earth-coloured tights, the drum platforms roll into the wings and as the dancers form a circle lying on the floor the orchestra plays the first chords of Beethoven’s 9th symphony. Dancers of the Tokyo Ballet perform the first movement, their movements suggesting primeval beings coming to life, classical ballet technique combined with strong contemporary movements, interrupted, as is always the case with Béjart, with a series of pirouettes or a double tour. The mood becomes stronger, with military overtones, and builds to a climax, where the dancers, who appear to be very young, meet the power of the music with precision and an increasing sense of drama.

© Kiyonori Hasegawa. (Click image for larger version)

The second and third movements are danced by the dancers of Béjart Ballet Lausanne, and the second movement starts with Lausanne’s Japanese soloist, Masayoshi Onuki, bounding onto the stage with a playful solo full of light, quick footwork and bouncy jumps. He is joined by the attractive American dancer Kathleen Thielman and as other dancers join them, all costumed in red tights, the mood is one of a folk dance, very lively and well danced. The third movement opens with the company’s leading dancer, Julien Favreau, centre stage, very slowly advancing forward with long, controlled developés. Favreau has been with the company longer than any other member and worked constantly with Béjart until his death in 2007, creating new roles and performing the major roles in the repertoire. This collaboration is immediately evident in his dancing; the control, the elegance, the care he takes with every movement reminds one of those dancers who were the great stars of the Ballet of the 20th Century. His partner in the long, slow adagio section, both in white, is the Spanish dancer, Elisabet Ros, another long-term member and a beautiful, expressive dancer. Much of the choreography of this section, danced bare foot, is inspired by Indian dance, with many stylised hand movements and balances on one leg.

© Francette Levieux. (Click image for larger version)

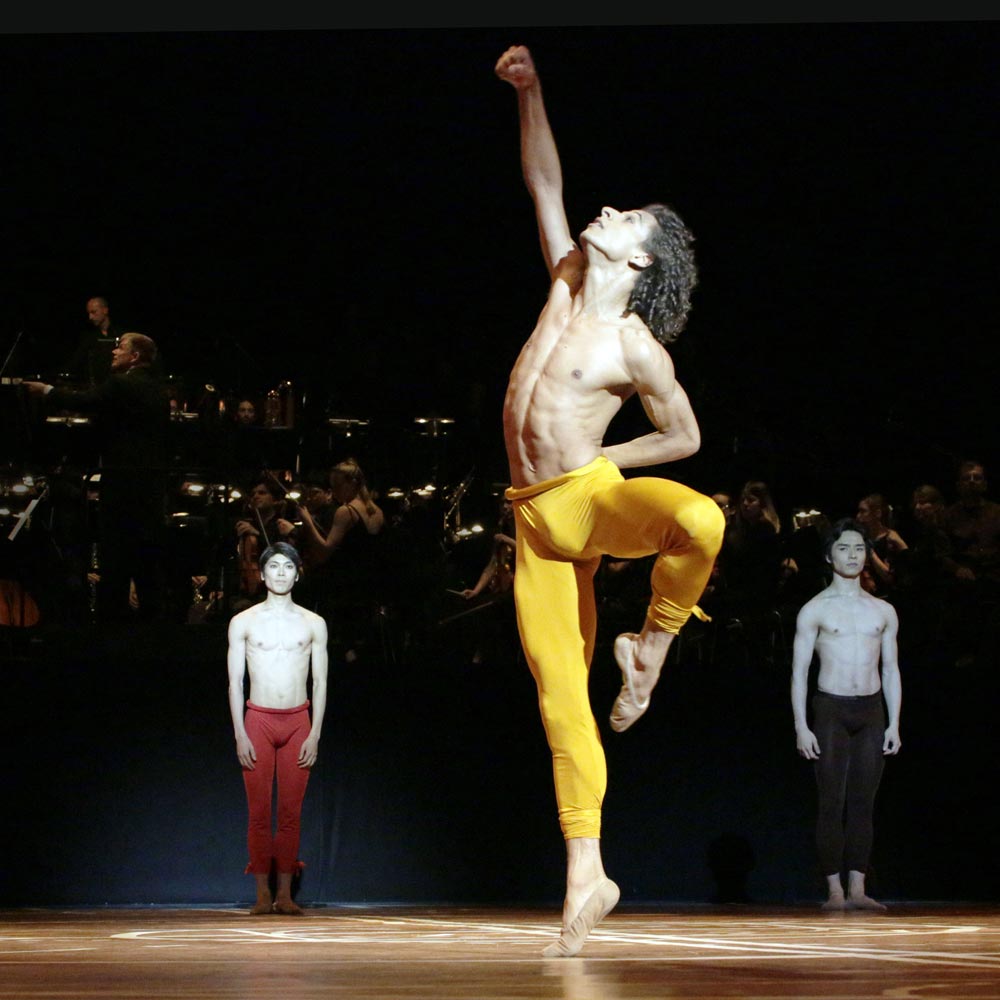

And so we come to the 4th movement and Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’. With the chorus first discarding their brown clothing for bright yellow, the movement starts with a virtuoso solo by Oscar Chacon, also in bright yellow tights, and he is joined by the principal male dancers of the three preceding movements for a quartet, challenging and competitive. More and more dancers from both companies enter the stage, all costumed in yellow, and they are joined by a group of ‘extras’, African dancers, as Béjart did with the original production in Brussels, using a group of African students from the university to underline the theme of ‘all people of the world’. The stage, packed with about 100 dancers accompanied by the soloists and chorus, glows in golden yellow, and while the power of the music takes over they form lines and circles, they hold hands and walk slowly towards the audience and finally circle and circle as the curtain falls.

It is, of course, a huge show but the commitment the dancers bring to it, the excellence of the dancing and sense of joy they bring to the final movement, make it a very theatrical experience. I felt that Maurice Béjart who, when I interviewed him shortly before his death, clearly expressed his love for his dancers, would have approved and been proud.

You must be logged in to post a comment.