© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev (and others)

Solo for Two: Zeitgeist, Mozart & Salieri, Facada

New York, City Center

7 August 2015

www.ardani.com

www.nycitycenter.org

Dancers should be allowed to have fun, especially when they’ve worked as hard as Ivan Vasiliev and Natalia Osipova. The Russian megastars are no strangers to the spotlight, and despite the fact that their offstage romance ended years ago (Vasiliev has just married Bolshoi soloist Maria Vinogradova), audiences remain fascinated by their history, craving more drama, which was the strongest element on the City Center stage on Friday night.

Arthur Pita’s Facada, the final work in the three-part mixed bill, is the only piece in which Osipova and Vasiliev actually dance together – and as such, is the most anticipated work on the program.

A contemporary take on the jilted bride, Facada could be subtitled Giselle’s Revenge. The work opens with the Lady in Black, played by character dancer Elizabeth McGorian, sitting coolly in a chair downstage, holding a large bouquet of white flowers; she soon reapplies her lipstick by using a butcher’s knife for her mirror. She moves across the stage like an arachnid, her svelte frame dressed in a black secretary skirt, long-sleeved lace blouse, and stllettos. The all-knowing, jaded black widow watches Osipova’s gleeful bride prepare for her wedding. Osipova is all giddiness, all anticipation. The music is a medley composed by Frank Moon who performs fado-esque guitar music onstage.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Abandoned at the altar by a screaming, non-committal Groom, the Bride weeps profusely – her tears creating a reservoir the Lady in Black uses to water her plants. Facada is almost worth it just for McGorian’s unimpressed stare at the audience as she ferries water back and forth. Her “Mmm hmmm, no surprise here” face communicates a thousand eye rolls.

Diane Wakoski’s poem “Dancing on the Grave of a Son of a Bitch” captures a sentiment more often fantasized about than enacted. But theatre is fantasy at its peak. After the Bride murders her former fiancee, a table is wheeled out over his dead body and Osipova gets to embody Wakoski’s solo wake.

© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

Osipova is at her best in this stint, stomping away with rhythmic abandon. With her jet black hair unkempt and unraveled and her taut body in a brief white nightie, she is positively feral. There is no semblance of happiness, and peace seems far away, but there is the catharsis of rage.

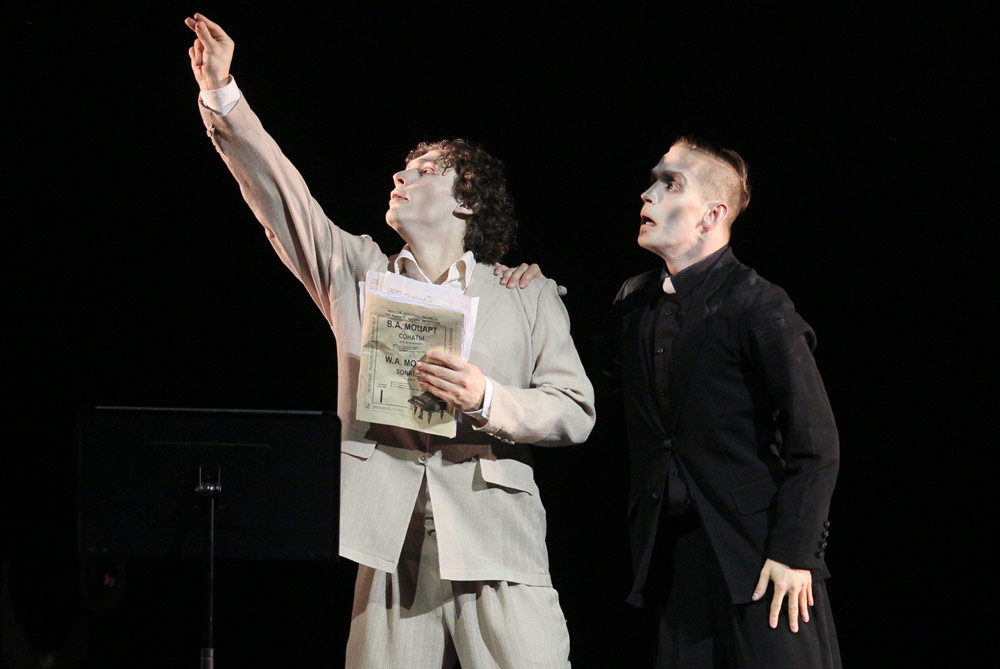

Mozart & Salieri is another theatrical work, carried mostly by the chilling visage of Vladimir Varnava – who also happens to be the creator and choreographer. Playing Salieri, Varnava’s face, in contemporary terms, echoes “The Dark Knight” – a cadaverous, white-powdered face with strong cheekbone shadows. If Varnava is the suffering mime, a modern Buster Keaton, Vasiliev’s Mozart – especially with his mop of sandy blonde curls, round eyes and rubbery smile – is Harpo Marx (the resemblance is striking).

© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

Mozart & Salieri is at times deeply heart-wrenching, often thanks to Varnava’s thespian skills. A reduction of Pushkin’s play by the same name, the work focuses on Salieri’s jealousy of Mozart’s natural, carefree genius, and Salieri’s attempt to poison him. The piece has charm, particularly when Vasiliev and Varnava sway to the same music, although it is a tad too long.

Using the myth of two musical giants, Varnava taps into the visceral jealousy and despair that haunts artistic rivalry. Hobbling across the stage with the walk of a feeble insomniac, Varnava embodies the existential crisis like a masterful Pierrot.

© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

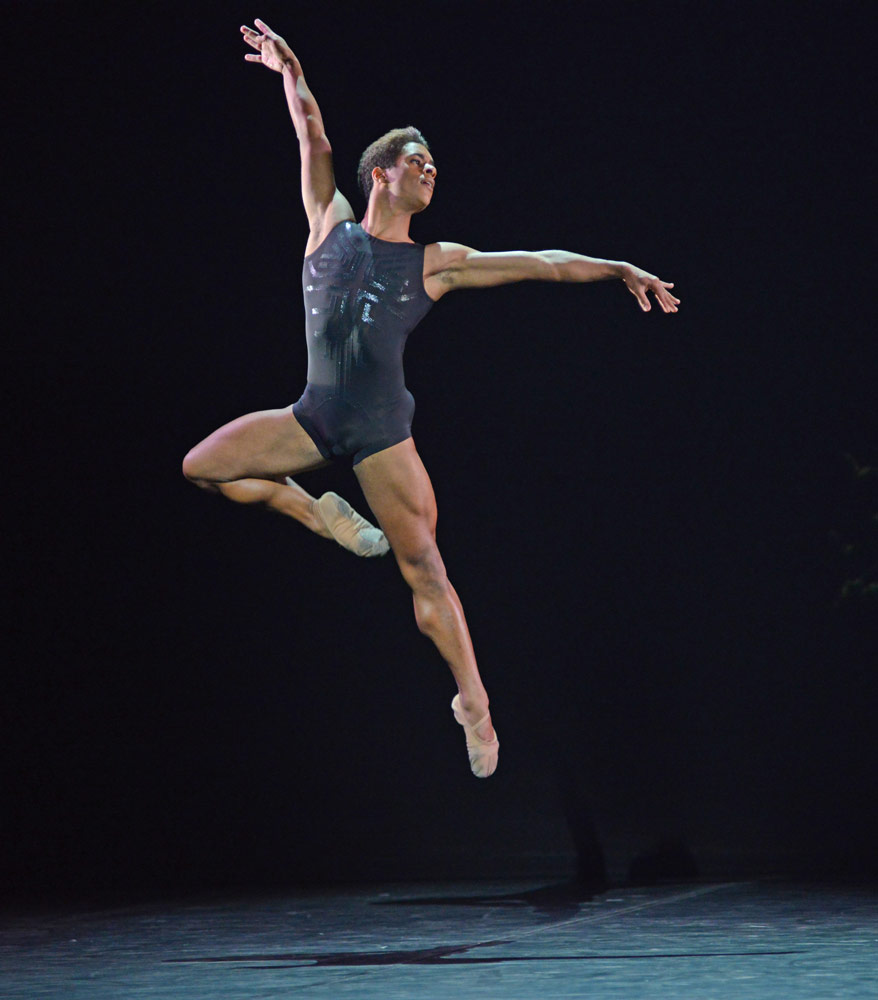

Osipova is the lone female in Alastair Marriott’s Zeitgeist, which opens the program, dancing alongside Royal Ballet guest artists Edward Watson, Marcelino Sambe, Tomas Mock and Donald Thom. Thanks to the score, Philip Glass’s haunted first Violin Concerto, Zeitgeist is imbued automatically with a sense of imminency and suspense. Sambe, the standout among the male “trio,” moves with an accomplished, unpretentious, old-soul gravitas that was a welcome surprise. Watson and Osipova worm around with the sinewy, extreme movements that have come to characterize so much contemporary ballet choreography. Zeitgeist is at times punishingly fast, and of course these two stars are up for it. But what is the value of such speed and athleticism? When anchored to musicality, it is exhilarating, but many of Marriott’s moves fall short of that, which leaves the form, and the gymnastics of it. While dancers such as Osipova and Watson are recognized worldwide for their unique gifts and their lithe capabilities, many principal artists in the biggest and most prominent companies can do these steps, at this speed. Contemporary ballet’s extreme extensions and contortions are now de rigeur, and as such, spectacle for spectacle’s sake, begins to lose its “wow” factor. Strictly as a vehicle for Osipova, she has better options elsewhere, whether they be her classical triumphs in roles such as Giselle or on the other end of the spectrum, with McGregor.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

All in all, it is not a program to go out of one’s way for, but dancers shouldn’t be kept locked in gilded cages. Midcentury greats like Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Lynn Seymour, Peter Martins and others of their ilk constantly juggled their regular company commitments with choreographers and experiments outside their regular milieu, frequently crossing the globe to do so. Bully to Osipova and Vasiliev for giving it a whirl; let’s see what they come up with next time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.