© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Opera and Hofesh Shechter Company

Orphée et Eurydice

London, Royal Opera House

14 September 2015

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

www.hofesh.co.uk

BBC3 broadcast Saturday 24 October 2015 at 18:30

Hofesh Schechter joins the ranks of choreographers who have directed (or co-directed in Schechter’s case, along with John Fulljames) Gluck’s Orpheus opera: they include Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan, Pina Bausch and Mark Morris, among others. There’s a lot of ballet music in the 1774 French version of Orphée et Eurydice that Gluck adapted from his earlier Italian-language original in 1762. The challenge for directors is to integrate singers, musicians and dancers without an opera audience wishing the dancers would just go away.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Schechter doesn’t entirely succeed. The production looks, and above all sounds, spectacular. The orchestra, the English Baroque Soloists conducted by John Eliot Gardiner, is placed literally centre stage, emphasising the power of music in the Orpheus myth. The musicians sit on a hydraulic lift, ascending to the heavens or sinking down to the underworld. They are the engine of the drama: key players – flautist, oboist, trombonists – stand up to be seen when their instruments are featured. Gardiner, his back to the singers and dancers, can’t see them in action. He is a magician, aided by experience and video monitors.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

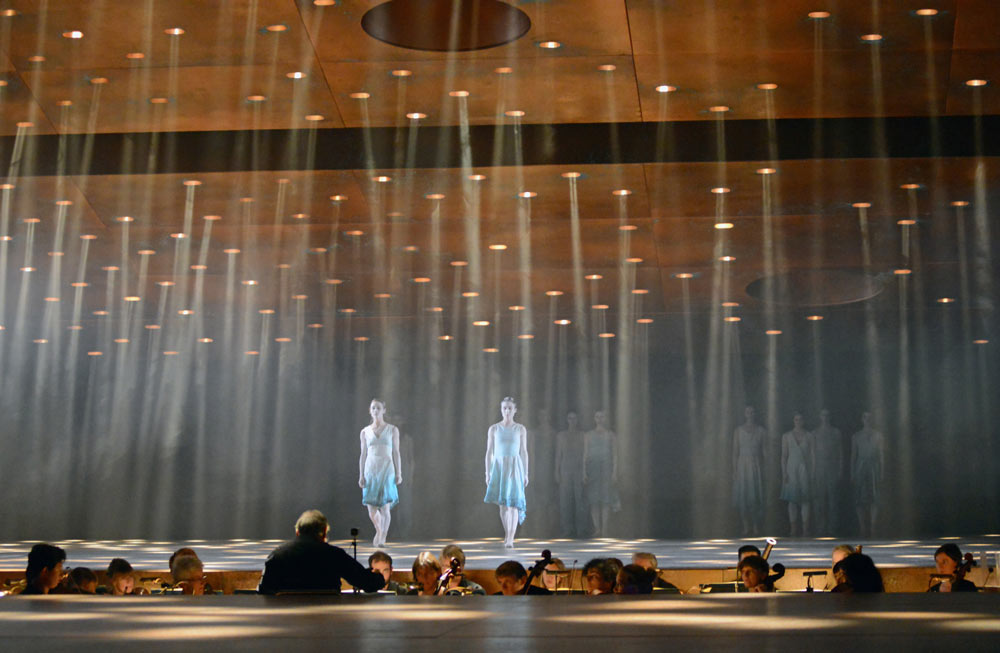

The Monteverdi choir and Shechter’s dancers from his own company move below, and occasionally above, the ranks of musicians. Conor Murphy’s mobile tiered set depicts Orpheus’ journey in search of his dead wife, Eurydice, descending from earth to Hades and the Elysian Fields. A bronze roof overhanging the stage serves as a sounding board for the music and as a lighting device: spotlights and ethereal effects shine through holes in its panels. (Lee Curran is the inspired lighting designer.)

The setting is austere and timeless/contemporary. The chorus wear mourning dress that looks vaguely Middle Eastern; the dancers’ costumes change according to the roles they play. At first they appear to be members of the community grieving with Orpheus over the death of his bride on their wedding day. Their ritual dance, arms raise in a semi-circle, resembles an Israeli folk-dance. Their funeral ceremony, burning a wicker effigy, is interrupted by the anguished howl of Juan Diego Florez as Orpheus calling Eurydice’s name.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

In this French version, Gluck re-wrote the role for a high haute-contre tenor – a virile voice very different from that of a counter-tenor or woman en travesti. Florez rages in desperation, defying the gods who took his young wife from him. When he laments alone, Amour (Amanda Forsythe) promises that he can regain Eurydice from the land of the dead, provided that he does not look at her on the return journey. Amour, a minx in a provocative gold lamé power suit and high heels, perches with the orchestra above Orpheus’s head. Behind the musicians, dancers skip merrily as happy spirits. No wonder Orpheus is mistrustful: his flamboyant aria at the end of Act I is defiant rather than hopeful. His is an extraordinarily sustained role in this act, requiring great power as an actor as well as singer. Florez is magnificent.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Act II, set in the underworld, contains music for Furies and Blessed Spirits as Orpheus searches for Eurydice. While the chorus is impressively threatening, male dancers as tribal Furies scamper and gibber, dreadlocks flying, like feeble fakirs from a bad production of La Bayadère. They hop in unison on one foot, then on two, simply walking off when the music ends and that for the Blessed Spirits begins. Florez has tamed the Furies by singing splendidly while standing on a chair, a harpist playing by his side as a substitute for Orpheus’s lyre. The staging at this point resembles that of an amateur recital.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

A flute introduces the dance of the Blessed Spirits, who are elevated on high in dip-dyed blue shifts. The solo flautist (Rachel Beckett) plays Gluck’s melodic writing tenderly; the dancers stand still, semaphoring hand gestures. It’s a nice idea, allowing the audience to listen without too much distraction, but the arm movements aren’t a subtle enough response to the flautist’s phrasing. When the dancing gets under way with skipping and bounding, Shechter’s inadequacy as a choreographer to match Mark Morris’s joyous inventions to baroque music is all too apparent.

Schechter is accustomed to creating his own, very loud, music for his company. His choreography is based on folk dancing and low-slung slouching runs, with dancers moving in massed formations. He is not adept at organising them in patterns and numbers to reflect the music’s structure, as Morris does. Both choreographers like their dancers to appear natural human beings rather than expert technicians, but where Morris’s dancers are fleet enough to be airborne, Shechter’s are earth-bound, hunched and far from beatific: not ideal as Blessed Spirits.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version

The celebratory dance that (almost) concludes Act III is better organised. Orpheus has retrieved Eurydice (Lucy Crowe) and lost her again by looking at her against his will. Their duet is agonised, expressing their longings for each other at cross-purposes. When she touches him awkwardly, they have none of the physical intimacy of dancers in a pas de deux. Only when he lies in despair by her dead body do they seem to have been lovers. Amour comes to the rescue, assuring Orpheus that his willingness to sacrifice his life means that he can have Eurydice back. But when the dancers rejoice (heavy sighs from opera lovers near my seat), she is nowhere to be seen.

Now dressed in yellow for the women and black kilts for naked-chested men, the dancers are a community once again, linking up in pairs and group formations. They split into two levels, some up high above the musicians, others in frenzied tribal dances at stage level. The music is very long, the choreography repetitive, the opera must surely be over . . . but the effigy of Eurydice from Act I is brought on and set on fire once again. Orpheus stands alone, presumably having hallucinated the previous acts in a delirium of grief before coming to terms with the loss of his beloved wife.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Overall, the austere staging is impressive, giving the music and voices pride of place. There are no modernising gimmicks, though one design choice looks ludicrous. Florez has to sit in each act on a prosaic chair borrowed from the orchestra’s seating, as though a last-minute provision to give him a rest. Working backwards from the surprise ending, maybe it’s a clue that this Orpheus never left the real world, dreaming his own myth. A pity, then, that he couldn’t have imagined better choreography to match the glorious singing in his vision scenes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.