© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Carmen, Viscera, Afternoon of a Faun and Tchaikovsky pas de deux

London, Royal Opera House

26, 28 October 2015

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

A second viewing of Carlos Acosta’s new Carmen makes his intentions clearer, thanks to the casting of Federico Bonnelli as Don José, Carmen’s besotted lover, in place of Acosta himself. Bonnelli brings a plausibility to the character that Acosta lacks in the role (in which he was first cast), giving the ballet a better perspective.

It’s not so much a ballet as a dance-theatre piece, mixing genres as Acosta did in his autobiographical Cuban production, Tocororo. To his credit, he has resisted the temptation to set Carmen in a cigar factory in Havana. Instead, the action takes place in a mythical hispanic arena, dominated by a vast circle: a blood-red moon or sun, a bullring, an enclosure from which there is no escape. Lurking within the orb is Fate, in the shape of a minotaur – a bull-horned man.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Carmen will be his creature, though she behaves as a free spirit. From the start, she taunts the men around her, flaunting her red skirt like a cape until they fling off most of their clothes. An exception is the ineffective officer, Don José, who is obliged to imprison her when she attacks a jealous woman with a knife.

He tries to restrain her in a cage, but she reins him in with her chain, a female spider toying with her victim. In the first cast, Marianela Nunez, hampered by a hideous wig, does her best to seem irresistible rather than vulgar, but her seductive technique is crudely choreographed. Acosta as Don José seems more bemused than smitten; Bonnelli succumbs to Laura Morera’s Carmen as though he’d never experienced anything like her kiss before.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Once lured to bandit territory, Don José is soon out of his depth and his uniform. Forced to hold a rifle by black-clad baddies, he shoots a passing banker by accident. The perfunctory death serves to drive Don José into a desperate duet with Carmen, to eerily wistful entr’acte music from Bizet’s opera. She puts her foot on his chest and drapes herself over him in lifts. Bonnelli’s craven ardour is more convincing than Acosta’s virile manhandling of naughty Nunez.

After a blackout, the corps de ballet and opera chorus assemble for a flamenco-style celebration, complete with stamping on tables and shouted Olés. It’s fun entertainment, part folk-dance, part musical show routine. Enter the toreador Escamillo, a celebrity, snapped by a singing paparazzo. Carmen immediately decides she has to have him.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

When Acosta dances the role, he acknowledges the crowd’s enthusiasm, and the audience’s, with wry humour: he’s used to this adulation. When Bonnelli is Escamillo in the first cast, he struts and preens like an operatic divo, slickly handsome.

In the ensuing duet for Carmen with Escamillo, her legs are her weapon of seduction, rearing priapically above his groin. They are interrupted by Don José in a frenzy of jealousy. When Carmen spurns him in favour of Escamillo, a tug of war breaks out in yet another duet, rather laboriously making the point that Don José is a broken man, Carmen a callous man-eater. Acosta’s graphic choreography runs out of ways of imparting further information about his heroine’s sexual rapacity.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The narrative line loses tension in a fortune-telling scene with a gypsy mezzo-soprano, a guitar player and Carmen’s two girlfriends, whose futures we don’t care about. She, of course, is doomed. The minotaur comes forward to suspend her from his horns. But there is a finale to unfold before she meets her fate, by which time the ballet feels too long.

The corps couple on rolling chairs to the famous Habanera, as Escamillo in a red suit of lights wields his cape in preparation for his bull-fight. The music stops and starts for Don José’s enraged solo, a man at the end of his tether. Both Acosta and Bonelli are compellingly distraught, stabbing Carmen as though they didn’t mean to. The minotaur claims her corpse in a superb coup de théatre at the end, as the circle descends in a field of crimson flowers.

Acosta’s Carmen is far from a disaster, propelled by committed performances and Tim Hatley’s dramatic designs. Martin Yates’s score, though, lets it down by chopping and changing bits of Bizet in oddly curdled orchestration. It oversells emotions that the performers are capable of expressing in movement, hammering home the theme of fate. Though this Carmen may not be a masterpiece, it’s more enjoyable than Mats Ek’s ironic version, taken into the repertoire in 2002 for a few flamboyant performances.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

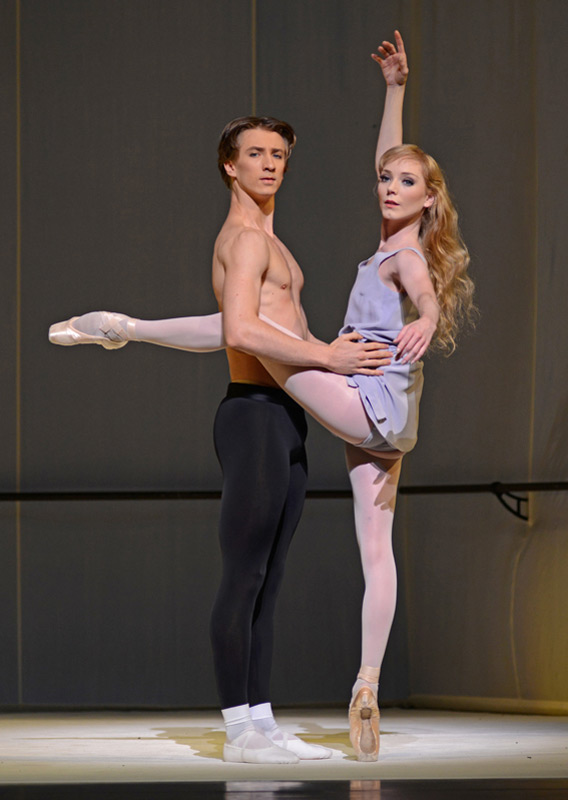

Carmen’s many duets are in sharp contrast to the courteous partnering in the other works in the programme. Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky pas de deux, danced by Iana Salenko and Steven McRae in the first cast, Marianela Nunez and Vadim Muntagirov in the second, is a joyous lesson in trust. The man is there when she needs him, but she is more than capable of looking after herself. Robbins’s Afternoon of a Faun (Sarah Lamb with Muntagirov, Lauren Cuthbertson with Eric Underwood) reveals the effect of touch on self-aware bodies. Both brief ballets were magically danced.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Liam Scarlett’s Viscera has a tender, rather sinister pas de deux at the centre of its three movements. Performed by Leticia Stock and Nehemiah Kish in the first cast, the woman seems in need of the man’s support, her long, slender limbs entwined around him, continually off-balance. When Laura Morera dances it with Ryoichi Hirano, she brings a sadness to her dependence on him, stepping ruefully away from him in farewell. The duet’s lovely ending is spoilt by having the man simply walk off into the wings, his role over. He should rather be swept away by the speedy couples in the perpetuum mobile last movement, marshalling the 14 dancers in a whirl of speed. Viscera deserves to be seen in a different context, instead of fronting a very mixed bill that makes for a long evening.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

You must be logged in to post a comment.