© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

All Balanchine II – Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Sonatine, Mozartiana, Symphony in C

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

26 January 2015

www.nycballet.com

Embarrassment of Riches

Some nights at the ballet you just get lucky: all the works are beautiful and the program is well balanced, and each of the casts is led by a ballerina who seems just right for the role. This was one of those nights. It wasn’t perfect, of course – there were a few squeaks from the orchestra, someone slipped onstage – but after all, perfection doesn’t exist, and if it did, it would be boring.

The program was all-Balanchine, a good place to start: Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Sonatine, Mozartiana, and Symphony in C. With the exception of the latter, all the works are from the seventies and eighties; they exhibit the ease of a master with absolutely nothing to prove. But then Mozartiana, one of his very last works, is also one of his most inventive and one of his most playful, despite its mournful opening. To produce the desired effect, Balanchine shifted around the movements of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Suite. This way, it proceeds from the sadness of the “Preghiera” (or prayer) to the wit and joy of the Theme and Variations. This works so well that one is surprised to learn that Tchaikovsky didn’t think of it himself. The Russian musicologist Solomon Volkov once wrote that before seeing the ballet, “I respected that suite but did not love it. I see know that I did not understand it.”

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

It is a program filled with musical delights: from the bombast of Gounod’s Walpurgisnacht (from the opera Faust) to the sparkling delicacy of Ravel’s Sonatine and Bizet’s youthful First Symphony. The orchestra, under the baton of its new music director, Andrew Litton, was mostly up to the task, with the exception of a few moments for the solo violin in Mozartiana and a squeaky clarinet in Symphony in C. What one notices most since Litton’s arrival is a new vibrancy and transparency of tone. The pianist Cameron Grant played the Ravel sonata with delicacy and refinement, serving the dance, but without slavishness.

In Walpurgisnacht, which opened the program, Sara Mearns displayed her usual command, a mix of power and fearlessness (with just the faintest touch of irony). Every entrance is an event, every turn and arabesque and backbend a dive into the unknown. One imagines she must be difficult to partner, because she doesn’t hold back. Adrian Danchig-Waring acquitted himself well, but there was little chemistry between the two. In her first entrance, accompanied by a sweeping melody on the strings, she walked slowly, grandly in a diagonal, her hand caressing her temple. She was a heroine in an adventure novel, a queen acquiescing to the adoration of her court. Mearns knows how to infuse every moment with drama.

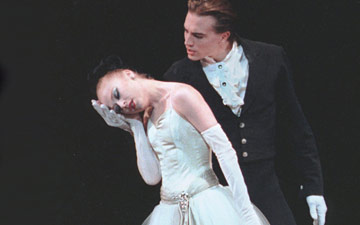

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

In contrast, nothing could be less grandiloquent than the pas de deux that followed, Sonatine. Originally created for two French dancers in the company, Violette Verdy and Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux, it carries a bit of their DNA in its insouciance, its sense of character and style, and its maturity. It is a danced conversation. The two dancers listen and respond to each other and to the music. Tiler Peck is more emphatic than Verdy was; what came naturally to Verdy – the hippy movement and provocative shoulders, the saucy hand on the hip – is a carefully constructed character for Peck. (Similarly, Joaquin de Luz makes more of the folksy flourishes in the choreography than Bonnefoux did.)

But, with her dance intelligence, Peck molds the ballet to her character. She expands and holds certain moments, such as her slow, rubato folding of the leg, a move I’ve come to think of as the Tiler Peck enveloppé, then accelerates whatever comes next, dancing around the music, like a jazz singer scatting. Perhaps the most appealing thing about this rather slender pas de deux is this sense of witty repartee. The two dancers are equals; they don’t need each other, but they choose to dance together. Sometimes she offers an arm, sometimes he does. Sometimes they’re together, sometimes they’re apart; in one of the ballet’s loveliest moments, they dance two contrasting phrases while advancing side by side, as the piano plays two overlapping melodies. They do their own thing, together.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

At times Mozartiana has a similar feel, particularly in the Theme and Variations section. The man (Anthony Huxley) and woman (Sterling Hyltin) take turns in solos of increasing difficulty, until finally they come together in a witty duet. She leads him, then he leads her, and then they split the difference. Everyone wins. Here, Hyltin, a naturally stylish and ebullient dancer, was wholly in her element; her backward-traveling bourrées were particularly lovely, as was the fetching way she flipped her wrists at the end of a port de bras. Huxley danced the devilishly-difficult role (a début) with astonishing clarity; his feet sparkled and the shapes he etched in the air were no less impressive. The partnering will take some time to catch up, and with it, one hopes, some glimmer of personality. For now, the beauty of the dancing will have to do.

The evening closed with a strong performance of Symphony in C. There were some hiccups, to be sure, particularly Gonzalo García’s wobbly turns. But the corps was in good form, synchronized and un-rushed, especially Meagan Mann and Ashley Hod. Teresa Reichlen’s dancing in the slow, sustained second movement flowed continuously, uninterruptedly, like a silken thread. She is the very opposite of Mearns – her dancing reveals not the slightest sign of effort or self-dramatization. Like Mearns’ command and Peck’s supple musicality, Reichlen’s effortless expansiveness is her signature.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Here lies the strength of City Ballet right now: a roster of exceptional principal women who differ in every way – musicality, build, approach, and personality. One’s allegiance skips from one to the next. It’s why we keep going back to the ballet.

You must be logged in to post a comment.