© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

21st Century Choreographers: Ash, This Bitter Earth, The Infernal Machine, Jeux, Paz de la Jolla

★★★✰✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

20 February 2016

www.nycballet.com

Down by the Seaside

Justin Peck’s Paz de la Jolla, a seaside romp set to Bohuslav Martinu’s 1950 sinfonietta for string orchestra, brought a welcome blast of summer to the Saturday matinee at New York City Ballet. In 2013, when it premièred, it was only Peck’s third ballet for the company. (The process of its creation was captured in the excellent documentary Ballet 422.) Three years on it still feels fresh, bubbling with energy. And, even though Peck’s first official story ballet, The Most Incredible Thing, premiered only this season, Paz contains what still may be his most successful moment of narrative invention.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

This story-within-the story comes in the slow, haunting second movement, a kind of nocturnal reverie. The dancers bend, sway, and interlock, creating patterns that give the illusion of waves and heaving surf. Sterling Hyltin and Amar Ramasar, the ballet’s leads (along with an unstoppable Tiler Peck) dance a shy and tender pas de deux, then lie down side by side. As if in a dream, Hyltin rises and allows herself to be drawn into the waves; the dancers form eddies around her, pulling her in further. As she realizes her predicament, her movements become more frenzied and Ramasar, awakened, dives in after her. The two appear to drown. But, this being ballet, all is soon well again and the two dancers join the raucous finale that brings Paz careening to a close.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The colorful 1920’s style beach-wear, by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung, adds to the sunny atmosphere and brings to mind other similar works, including Bronislava Nijinska’s Le Train Bleu and Jerome Robbins’ In G Major. The hyper-fast, spinning-on-her-own-axis choreography for Tiler Peck is very reminiscent of her part in The Most Incredible Thing. Justin Peck (no relation) seems to be bewitched by her speed, but perhaps it’s time he thought of new, less obvious ways to test this unflappable dancer. In any case, this ballet reveals a more vulnerable, more dreamy side of the choreographer.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

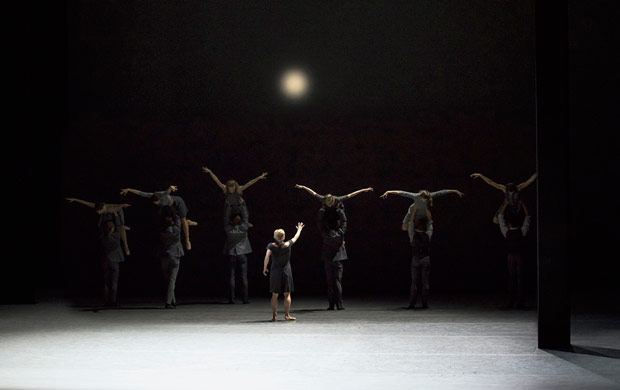

Paz closed a program that had begun with a series of short works (by Peter Martins and Christopher Wheeldon), before moving on to Kim Brandstrup’s Jeux, from last season. Handsome to look at, with its film-noir lighting and flattering black 1940’s style dresses (by Marc Happel), Jeux nevertheless proves to be rather thin, a not-quite-convincing cross between Balanchine’s La Valse and Shirley Jackson’s sinister short-story, “The Lottery.” A blindfolded woman, Sara Mearns, is harassed by a sinister cluster of couples. Still blindfolded, she encounters a youth (Adrian Danchig-Waring) wearing jeans and carrying a ball. Then, as the other couples swirl around her, she seems to lose her mind, repeatedly clutching her head and smoothing her dress. Finally taking matters into her own hands, Mearns places the blindfold over the younger man’s eyes and lowers herself onto his body just as the curtain falls on the scene. The music is Debussy’s eponymous 1912 “poème dansé,” which Vaslav Nijinsky turned into a ballet about a love triangle. Brandstrup fails to find his way through it, resulting in a ballet that is more inert than intriguing.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

At least it was well danced. This cannot be said for the first ballet of the evening, Peter Martins’ 1991 Ash, a relentlessly difficult if thankless work full of tricky partnering and virtuosic, topsy-turvy, off-kilter moves. Zachary Catazaro was outdone by the choreography, nearly dropping his partner (Ashley Laracey) at one point, and looking breathless and rather lost throughout. Two of the men in the small ensemble, Sebastian Villarini-Velez and Spartak Hoxha managed to bend the choreography to their advantage in short solos, traversing the stage with exciting space-devouring jumps and slides. The other Martins work, The Infernal Machine (set to music by Christopher Rouse) is an aggressive, rough-handed pas de deux, danced here with grit and impressive flexibility – there are a lot of splits – by Unity Phelan and Preston Chamblee. Chamblee, in his first featured role, shows potential as a leading man. It will be nice to see him take on other, more nuanced parts.

In between, Sara Mearns and Tyler Angle danced a duet created by Christopher Wheeldon for Wendy Whelan in 2012, This Bitter Earth, set to a rather sentimental remix by Max Richter of Dinah Washginton’s eponymous song. Like other works created for Whelan by Wheeldon, it has a diaphanous simplicity meant to highlight Whelan’s honest, straightforward, and un-varnished stage manner. When she danced it, Whelan was all angles and vulnerability. Mearns, a very different sort of dancer, has her own take, more muscular and dramatic. Where Whelan fluttered like a leaf, Mearns falls with a kind of fateful abandon. It’s not much of a pas de deux, really; one almost wishes it had been retired after Whelan’s final season. But it lives on, and, in Mearns’s hands, it still breathes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.