© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

After the Rain, Strapless, Within the Golden Hour

London, Royal Opera House

12 February 2016

★★★✰✰

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

Christopher Wheeldon made his reputation with cleverly crafted one-act ballets to attractive music before trying his hand at telling stories through dance – in musicals as well as ballets. The Royal Ballet’s all-Wheeldon triple bill features two of his plotless works for American companies as bookends for a narrative commission: Strapless, inspired by a notorious portrait by John Singer Sargent. Wheeldon’s talents are on display, as well as the Royal Ballet’s dancers. A pity, then, that Strapless has been exposed without previews to sort out its weaknesses.

The story of how the portrait of Madame X came about is an intriguing one, imaginatively told in a book by Deborah Davis, who wrote one of the programme articles. (A Royal Ballet programme is essential for background information and illustrations of Sargent’s subjects.) Both Sargent and his subject, Madame Amélie Gautreau, were Americans on the make in the Paris of La Belle époque. He needed to make his name in the art world and she craved what we now call celebrity status in Parisian high society. She could only do so by marrying a rich man, twice her age, who would fund her ambition. It all went horribly wrong when her portrait was displayed with one glittering strap slipped from a shoulder. Evidently shameless, she was cast out of society and never recovered.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Wheeldon starts the ballet just before the portrait is about to be unveiled and then flashes back in time to establish the characters and their contexts. Bob Crowley’s sets frame the action, noisily trundled in and out (on the opening night). Though his outfits for Amélie are stunning, displaying her neck, shoulders and embonpoint like the low-cut dress in Sargent’s portrait of her, the costumes for the corps of onlookers pose problems. All in black, they are hard to discern against a dark backdrop; hats and bustles render the women indistinguishable, while top hats for the men make them unrecognisable.

Initially, Wheeldon is in Ashton territory, with Amélie as glamorous Marguerite or high-maintenance Natalia Petrovna, with a comical husband easily cuckolded. Jonathan Howells as Monsieur Gautreau is soon sidelined, while Natalia Osipova takes centre stage as a brazen beauty. She is luscious, shoulders pinned back to flaunt her bosom, constantly twirling to show herself to best advantage. In black, she’s Odile, dangerously tempting; in red, she is literally a scarlet woman with her lover, Dr Pozzi (Federico Bonelli, outrageously handsome).

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Sargent’s portrait of Pozzi in his dressing gown, one hand on his belt as if about to remove it, reveals that the doctor, a gynaecologist, was a roué. Wheeldon’s Pozzi certainly knows how to pleasure a woman as he engages with Amélie in a MacMillanesque pas de deux. Osipova drapes the dressing gown around her at the end of their explicit coupling as though she’s a triumphant prize fighter: she’s had him, not the other way round.

There’s a nice cameo for Kristen McNally as Madame Pozzi, highly indignant in angry little steps. You have to read the synopsis to work out who she is, and check wikipedia to discover that Elizabeth McGorian must be Amélie’s mother, Marie Avegno. They and other society figures may well have backstories but we don’t know enough about them to care.

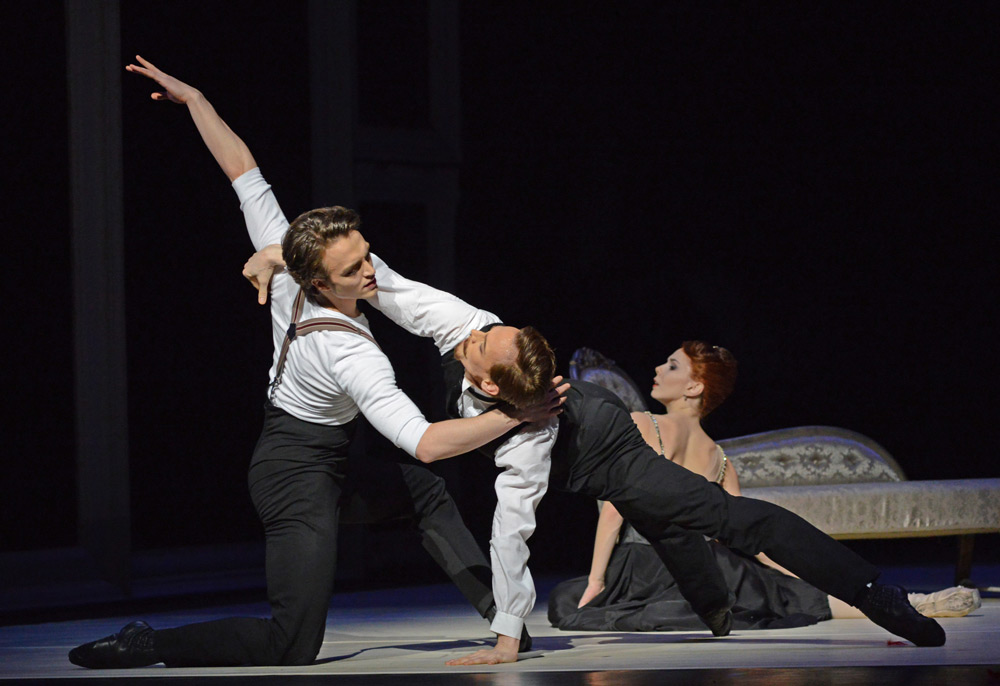

Wheeldon’s depiction of Parisian society is as stereotypical as that in American in Paris. Mark-Anthony Turnage’s score even sounds like George Gershwin’s blaring music. The fashionable set pose and gossip – then hover like ravens; bohemians frequent nightclubs with can-can girls and dancing waiters. Edward Watson as Sargent finally comes into the picture, busily sketching his lover, Albert de Belleroche. (Programme articles claim that Sargent was a closet homosexual.) Belleroche is a cameo role for Matthew Ball, who serves mainly as a ghostly double for Amélie in Sargent’s fevered imagination.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Amélie is passed between Sargent and Belleroche in an ingenious triad before her final pose for the portrait is decided, her profile echoing Belleroche’s. When the painting is exhibited in the 1884 Paris Salon – the first time a reproduction of the portrait is shown on stage – the black-clad corps turn on Amélie. Stripped down to a white leotard, Osipova is a wounded bird, her once-proud shoulders hunched in shame.

It’s hard for a modern audience to understand the outrage. Amélie Gautreau was known to have lovers – everybody did. Was a fallen strap, later painted back in place, really so calamitous? Sargent was reviled for the inept execution of a painting that has since been admired as a masterpiece. Wheeldon can’t account for the hypocrisy and xenophobia of a Parisian beau monde that resented American success.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

He ends the ballet, as he did Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in modern times. Spectators cluster round the portrait in a museum (it’s in the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York; a study for it is in the Tate in London). Watson, as a gallery guide, points out its virtues. Osipova, vulnerable in her white leotard, mingles amongst the crowd. The implication is ambiguous: according to the synopsis, she has achieved the fame and immortality she craved; but the glory is Sargent’s, not hers. Madame X remains anonymous to most viewers – though no longer to Wheeldon’s audiences.

Osipova, as interestingly beautiful as Sargent’s model, makes the most of her stage presence. There isn’t distinctive enough choreography for her to account for who Amélie is and whether she is more than a sexy social climber. Her downfall and humiliation are abrupt, inexplicable. Sargent’s urge for acceptance is underwritten, his homoeroticism too overt. Wheeldon’s storytelling tends to be overly literal, while leaving supporting characters as ciphers. Turnage’s insistent music doesn’t help define the milieux in which Sargent and Amélie moved.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

After the Rain, to Arvo Part’s often used music, concludes with a soulful pas de deux in which the woman wears a body-revealing leotard like Amélie’s ‘naked’ one. The pas deux has nothing to do with what has gone before, an athletic neo-classical sextet in which the women’s legs are wielded like weapons. The duet, in contrast, is dreamily tender and open to interpretation as a farewell, a fantasy or an affirmation of love. The woman drifts in her partner’s arms, held off-centre in sculptural poses as Part’s piano notes plink away. Marianela Nunez and Thiago Soares performed it poignantly.

Within the Golden Hour, made for San Francisco Ballet in 2008, was seen in that company’s Sadler’s Wells season in 2012 (and in Paris in 2014). It is Wheeldon at his best in effective corps patterns and attractively quirky duets. Ezio Bosso’s music, like Part’s, provides repetitive rhythms that let the choreographer go anywhere he likes. The costumes, designed by Martin Pakledinaz to resemble Eastern temple dancers, are unflattering in the extreme.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The ballet begins and ends as a community celebration, with three featured couples. Beatriz Stix-Brunell and Vadim Muntagirov were witty and charming in the first duet to a playful waltz; Lauren Cuthbertson and Matthew Golding danced the slo-mo sculptural pas de deux; Sarah Lamb and Steven McRae had the one where she seems an underwater mermaid, relying on his support until she swirls away. In between came a combative duet for Luca Acri and Marcelino Sambé, sharing the same steps but never making contact.

The conclusion is irresistible, with all 14 dancers merging into a pulsating perpetuum mobile mechanism that could continue long after the curtains close. The audience goes away happy, content with Wheeldon’s dance-making skills even if Strapless has yet to be sorted out as a coherent story ballet.

You must be logged in to post a comment.