© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

English National Ballet

She Said: Broken Wings, M-Dao, Fantastic Beings

★★★✰✰

London, Sadler’s Wells

13 April 2016

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.ballet.org.uk

Tamara Rojo has proved adept at attracting publicity and sponsorship for English National Ballet. She has refused to be intimidated by financial constraints, daring to take risks with commissions while maintaining the company’s classical base.

Choosing to showcase female choreographers for She Said has garnered headlines, previews and interviews with Rojo herself. The fact that she had not danced a work by a woman in her career so far is an accident of timing. Her two main companies, the Royal Ballet and English National Ballet, have performed works by female choreographers without making an issue of their sex. Wonderful roles for women (far more than for men) have been created by male choreographers.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

A specifically female sensibility is more evident in the body of work of modern or contemporary dance makers choreographing for their own choice of interpreters: Martha Graham and many Americans, Siobhan Davies, Cathy Marston and others in Europe, to name just a few. In bringing together three women from different backgrounds to create for dancers they didn’t know, Rojo has simply shown that some choreographers are more skilful than others – not that they have distinctively female voices.

The most ambitious and best-realised work on the triple bill was Broken Wings by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, with dramaturgy by Nancy Meckler. (Both had collaborated on A Streetcar Named Desire for Scottish Ballet.) Ochoa took up Rojo’s suggestion of the painter Frida Kahlo’s life and work, casting Rojo as Kahlo. So much colour and spectacle is packed into the 50 minute piece of dance theatre that it feels like a pilot for a 90 minute ballet in two acts.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

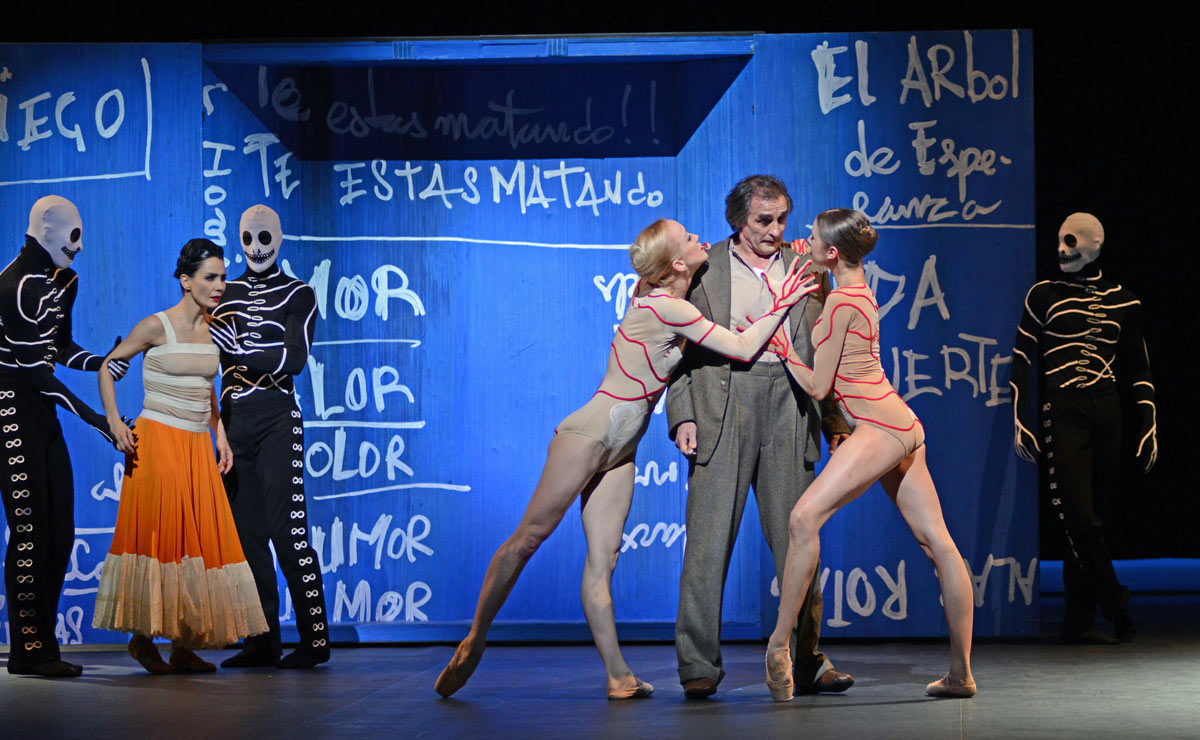

It starts and ends with a black box watched over by skeletons celebrating the Mexican Day of the Dead. Frida emerges from the cube, which then becomes her cell: a white hospital bedroom in which she was isolated after a horrible accident with a tram in which she was travelling. Trapped, she summons up a carnival of extravagant figures – her alter egos or muses: they are men in Mexican skirts with bare torsos painted in vibrant colours, and extravagant headdresses. They tower over tiny Rojo, dressed in a strappy costume evoking the steel corset she had to wear after her accident. But she is in command of her creatures, giving them life through her art.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Out of the box comes the painter Diego Rivera – Irek Mukhamedov in a fat suit, an older man besotted with much younger Frida. What a partnership he and Rojo could have made! He makes Rivera into a comical, lovable rogue and philanderer instead of a political activist thug. Wisely, Ochoa and Meckler never have either of the painters wield a brush; just as wisely, the dancers don’t need to prove that they are virtuoso performers as well as ‘real life’ characters. If the piece had time to expand, even more could be made of their turbulent relationship.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Kahlo’s life was plagued by disaster. One of her many miscarriages is depicted by a red thread wound out of her innards in her blood-spattered cell. Philandering Rivera takes a young firecracker as a mistress (Begona Cao) and Frida is beset by her demons and the mocking skeletons in a danse macabre. Images of birds and other strange creatures, including a female deer, are all drawn from her paintings. (The brilliant designs are by Dieuweke van Reij, the Mexican-inspired music by Peter Salem.)

At the end, Frida is pinned to the wall of the cube like a butterfly by Rivera and put back in her box like Petrushka. From the top, a bright, unconquerable spirit re-emerges. Broken Wings makes a powerful case for a woman who transformed her physical pain into art, sending us back to the paintings so vividly evoked.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

M-Dao, the middle piece, retells the Classical Greek legend of Medea as a love triangle in which she is the wronged woman. Chinese choreographer Yabin Wang handicaps her heroine (Laurretta Summerscales) with a single pointe shoe, perhaps representing her fettered soul. She moves in a shadowy world of silk and shifting video effects until she confronts her treacherous husband Jason (Fernando Bufala) and his new wife (Madison Keesler). A chorus of dark-clad figures amplify Medea’s agonies.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Jealousy is a private emotion that gnaws away, distorting reason (as Leontes reveals in Christopher Wheeldon’s account of The Winter’s Tale). Wang’s choreography, combining ballet, martial arts and traditional Chinese dance, has no memorable imagery or insights into Medea’s obsessive anger. The tragic denouement behind a silk curtain is obscurely ambiguous. Medea kills two figures, one of whom appears to be female. Did she deludedly think she was killing Jason and his young wife, while actually murdering her children? But in the legend, Medea deliberately deprived Jason of his sons and heirs. This is a muddled ending to a turgid piece that outstays its interest.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Fantastic Beings by Canadian choreographer Aszure Barton has a fantastic start to rousing music by Mason Bates. Beneath an intermittently staring eye, twenty dancers in mottled bodysuits come and go in choreography that uses ballet in inventive ways. The acrobatics are never too distorted, the step combinations respond to the music’s waywardness and everybody has a chance to show what they can do.

But because the dancers are anonymous on a dark stage and the music becomes relentless, the piece seems interminable. Eventually the background lightens and the entire ensemble come out in fringed gorilla outfits for a whirling finale that goes on for a long time. Fantastic Beings may have been fun to create and dance but it fails to keep its audience engaged.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

As the commissioner of the triple bill, Rojo has succeeded in securing one really stimulating work in Broken Wings. As director, she should be aware that the programme was ill-balanced, with works that were too long and too darkly lit for anyone not seated in the front row. And the intriguing front cloth by Grayson Perry, with its references to Kahlo’s imagery, put in an all-too-brief guest appearance, easily missed by late arrivals and early leavers.

Hi, my boyfriend is a huge fan of the figure of Frida Kahlo. His birthday is coming soon, and I like to know if there is representation planned in France for this ballet ? or if it’s possible to get video of the show ? It will make the most perfect gift for his birthday. Thank You.

Mickael

Hi, Not aware of anything but best to ask the company direct at http://www.ballet.org.uk,