© Regina Brocke. (Click image for larger version)

Gauthier Dance

Marco Goecke’s NIJINSKI

Stuttgart, Theaterhaus

22 July 2016

Gauthier Dance webpage at theaterhaus

www.theaterhaus.com

Marco Goecke’s choreography might not appeal to the strictly classical ballet lover. But Gauthier Dance’s most recent premiere, NIJINSKI, at Theaterhaus Stuttgart shows that Goecke’s high-frequency movement can breathe new life into the past, a past that was itself new and challenging once.

Vaslav Nijinsky is forever associated with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, the early 20th century company celebrated for merging dance, contemporary art, and music in intriguing and groundbreaking ways. Ballet lovers will recognise photographs of Nijinsky posing with an upward gaze and tilted palms as the Faun, the sad-clown-faced and hunched-shouldered Petrushka, or the wilted-armed Rose. Today we can appreciate that these roles were once innovative – if we now recognise them as important, and rather old-fashioned, markers in ballet history.

Stuttgart is home to some of today’s most innovative and productive dance makers. John Cranko and Marcia Haydee’s support of emerging choreographers at the Stuttgart Ballet in the seventies and eighties resulted in early works by Forsythe, Neumeier, and Scholz. In the last twenty years the company’s director, Reid Anderson, has furthered this legacy, providing a platform for resident choreographers Marco Goecke and Demis Volpi, not to mention numerous other opportunities for guest choreographers. As a former Stuttgart dancer, Eric Gauthier broadens the scope of innovative dance in Stuttgart with his Gauthier Dance offering contemporary dance performances as the resident dance company of the Theaterhaus Stuttgart.

NIJINSKI neatly lassos this altogether using Goecke’s avant garde movement style: often hectically fast-paced movement that mostly abandons a traditional ballet structure, to give the Stuttgart audience an abstract impression of Nijinsky’s life and contribution to Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Goecke’s work is well known, though appears somewhat misunderstood by the local Stuttgart audience. Theaterhaus Stuttgart’s T1 black box stage, however, provides a smaller and more intimate performance space for viewers to explore the details within Goecke’s choreography.

A predominantly dark and empty stage, with light design by Udo Haberland, establishes the prologue to a typical Goecke dance experience. As dancers begin to scurry and twitch, the first impression is wary: how can we endure this high-tension movement for eighty minutes straight without an interval? But as the dancing unfolds, it becomes clear why Goecke’s vocabulary is right for this piece. Dim lighting highlights the quick movements – the blur and swirl of fast-paced shuddering limbs illuminated against the dark background causes visual vibrations, a high-frequency layer of tension draped over classical Debussy and Chopin (recorded) scores.

© Regina Brocke. (Click image for larger version)

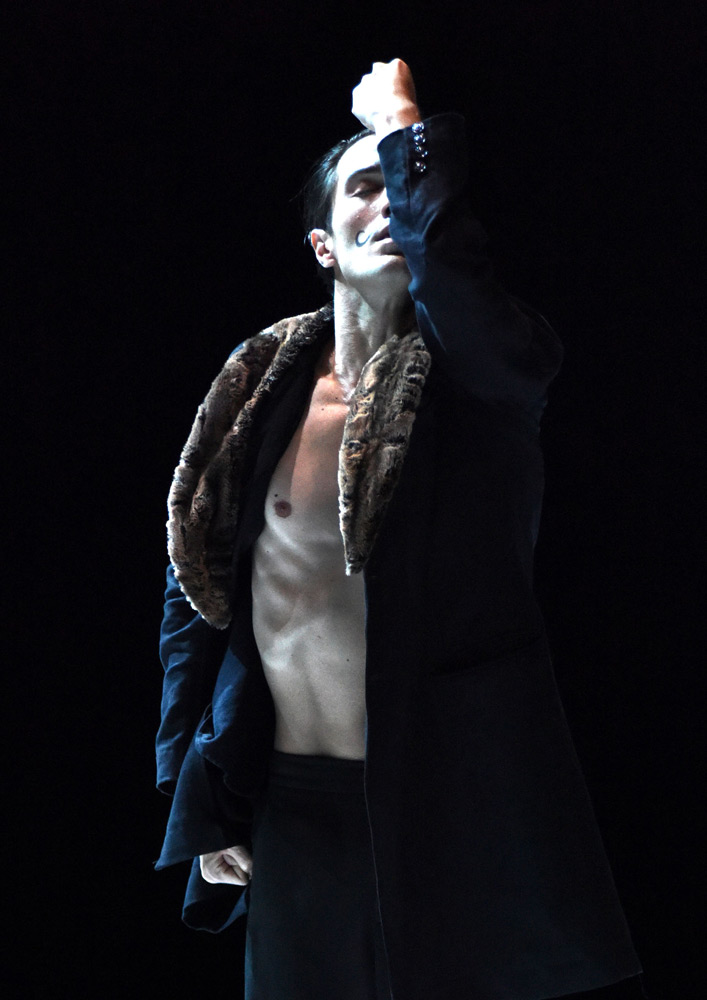

A simple blouse or jacket identifies different roles in an otherwise uniform world of black-slacked, shirtless (or neutral camisoled) dancers with hair-slicked down (sets and costumes by Michaela Springer). We witness the different phases of Nijinsky’s life: pursuing a ballet career, sexual awakening, confrontation with fame and greed and ultimately succumbing to madness. The aggressiveness of Goecke’s movement provides a stark contrast to the simplistic grace of the Nijinsky-era poses – brief moments of stillness creating breaks in the frenzy. Much of Goecke’s approach relies on this contrast: light against dark, fast against slow, hard against soft, and even reality against fantasy.

On July 22nd, Maurus Gauthier gave a strong and multi-faceted performance in the title role. Nearly always onstage, his task was to reveal the effort, rather than conceal it, as his character explored movement as self-expression. The shine of sweat against his back, and use of sound as an extension of movement (loud breathing, grunts, yells and whispers), provided human glimpses into a character that, until now, we only know from carefully posed photographs. Over time, an emotional layer seemed to spread over the visual in M. Gauthier’s interpretation; we could identify Nijinsky’s state of mind, and the building effects of stifling his true self, as he developed his public persona.

© Regina Brocke. (Click image for larger version)

Maurus Gauthier danced a particularly intriguing duet with Luke Prunty that paired parallel-limbed motifs from Diaghilev’s Afternoon of a Faun with images of sexual awakening in Goecke’s choreography (a hand reaches to pluck an outstretched tongue like a ripe piece of fruit). The two men danced in a seamless catch-and-release exchange – a moment of calm within the storm.

David Rodriguez’s portrayal of Diaghilev showed a good example of how Goecke uses humor in his work. Wearing a fur-collared coat and one-sided curly mustache, the impresario strutted, nitpicked and sometimes wound himself into a rage. It was refreshing that Goecke’s work didn’t always take itself too seriously, which in turn offered more honesty to the sincerer moments.

© Regina Brocke. (Click image for larger version)

There are opportunities for each dancer in the ensemble to be featured. While Nijinsky dreams, dancers appear in solos meant to suggest other great Ballets Russes dancers. These solos provide moments of straight Goecke choreography without much hint of historical context. They do, however, highlight how Gauthier’s dancers, with both strong classical ballet backgrounds and solid contemporary experience, execute Goecke’s movements with a fascinating combination of control and abandon. Their ability to push the limits of tempo while remaining grounded makes each individual interpretation the more interesting.

The story is not entirely linear, and Goecke provides his reason for this in the program notes: “the evolving artwork is more important than an external logic. For me, endeavouring to choreograph a purely logical ballet that accords strictly with its narrative would be too restrictive for the creative process.” Keeping this in mind, the viewer only needs a basic understanding of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and Nijinsky’s climb from student to star, to schizophrenic patient, to accept Goecke’s work.

© Regina Brocke. (Click image for larger version)

Our ability to interpret, however, was hindered when Eric Gauthier addressed the audience before the performance, providing a detailed outline of what would take place onstage. (When following a linear path, questions arise: why does the muse Terpsichore, Garazi Perez Oloriz, not appear again after the first twenty minutes, for example?) Although such an introduction may have catered to the Stuttgart audience, it gave too much emphasis on narrative, and inhibited them from fully appreciating the abstract nature of the piece.

Goecke communicates Nijinsky’s inevitable surrender to madness in a final scene where Maurus Gauthier obsessively scribbles circles onto the floor. This is a clever analogy; drawing a perfect circle is almost as unattainable as reaching perfection as a dancer. With this simple reference, Goecke relates Nijinsky’s story to dance as an art form: there is no perfection – movement is living artwork, and each signature is as individual as the bodies used to communicate it.

One scene hovers above all the rest: a fairy (or maybe insect) duet, where two ensemble dancers, wearing transparent blue wings on their backs, dart across the stage shivering and shaking their arms. Here Goecke’s choreography gives a fresh take on an old thought: sylphs of the past were weightless and ethereal, making flight seem effortless; sylphs of today are alive and energetic, drawing inspiration from the world around them to elevate and suspend belief – and carrying today’s audience along with them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.