© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Dec. 7: Four Corners, Untitled America, Revelations

Dec. 9: Four Corners, r-Evolution, Dream, Revelations

★★★★✰

New York, City Center

7, 9 December 2016

www.alvinailey.org

www.nycitycenter.org

American Stories

It’s not all Nutcrackers this time of year, thankfully. At City Center, December is synonymous with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Which, of course, means wonderful dancers performing in the company’s famously generous, extroverted style, about as far from the haut cool of New York City Ballet as one can get. There is no limit to how often one can see Ailey’s 1960 masterpiece Revelations. The elation is always the same. This is a good thing, since it seems to close almost every show. The miracle is that the dancers perform it night after night with the same energy and reverence – they don’t take it for granted.

Fortunately for them, there are new works to sink their teeth into. Since taking over in 2011, Robert Battle has been keen on bringing in dances from a range of choreographers outside of the traditional Ailey sphere (Paul Taylor, Wayne McGregor, Ohad Naharin), but also encouraging talent from within. Whether one likes these works or not – the record is hit or miss, as it is most places – it’s impossible not to notice that the company’s dancing has developed new colors. Dancers keep emerging from the ensemble as powerful voices, and growing from year to year. Jamar Roberts has been a force for a while, but lately, in works like Ronald K. Brown’s Four Corners and Rennie Harris’s Exodus, he has become monumental, with his devastating blend of power, amplitude, and vulnerability. Watching him fold and twist that giant body into Brown’s rounded, 3-dimensional movement is a wonder. On the other end of the spectrum, the relative newcomer Chalvar Monteiro, small-ish, quick, sharp, emanates a sly wit and intelligence, as if imparting his own personal story from the stage. You can’t take your eyes off of these dancers, and the same goes for Belen Pereyra, Jacquelin Harris, and Jeroboam Bozeman, among others. The list is long.

On Dec. 7 and 9, I caught two of the season’s three premières, Kyle Abraham’s Untitled America and Hope Boykin’s r-Evolution, Dream. (The third is a company première of Johan Inger’s Walking Mad.) In these two works, Abraham and Boykin engage social issues, or at least attempt to do so. Abraham, whose Untitled America overtly addresses the pain and loss of incarceration, is the more successful on this front. Boykin’s r-Evolution, Dream, inspired (loosely) by Martin Luther King’s speeches, has trouble integrating its theme into the rather upbeat, even light-hearted, feel of the work.

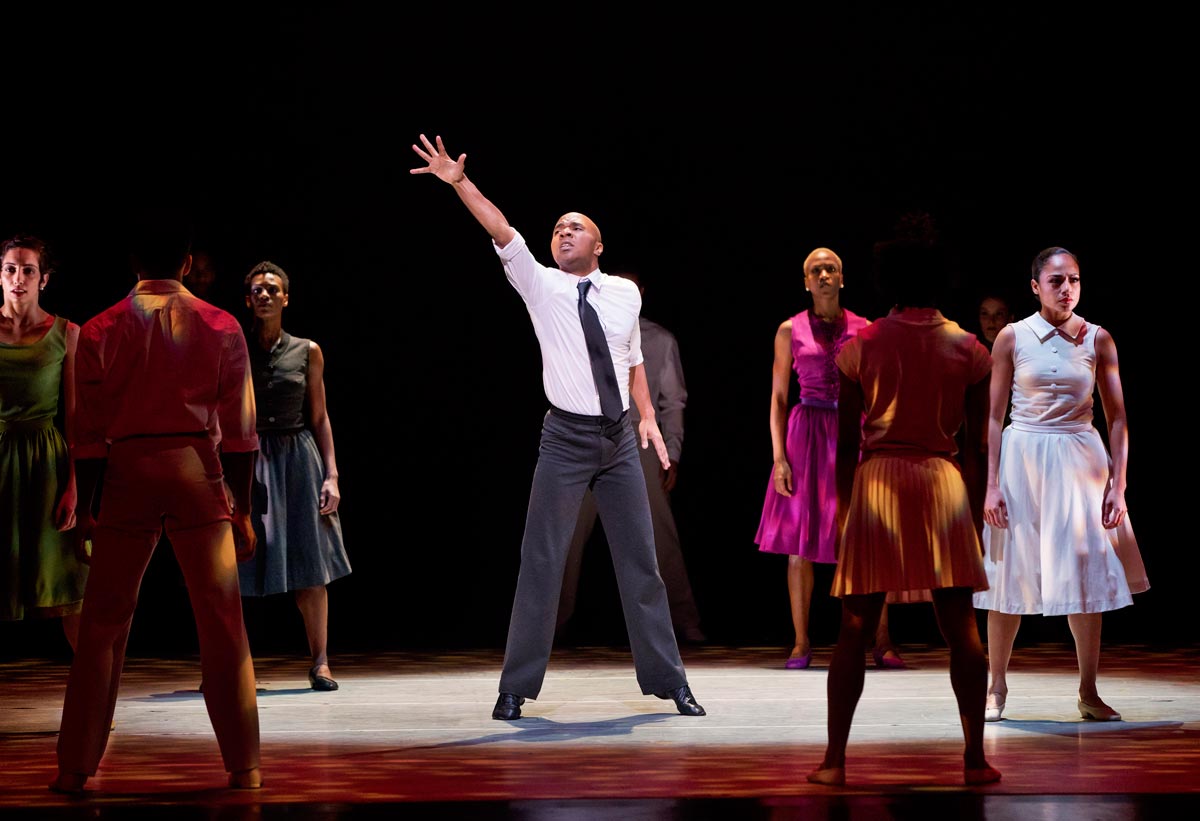

Which is not to say that there isn’t a lot of pleasure to be had from r-Evolution, Dream. It turns out to be something of a 1950’s period piece, with jazzy rhythms and steps, a vivid, witty use of the dancers’ faces and upper bodies, a large cast, and a wonderful, bebop-inspired score by Ali Jackson, of Jazz at Lincoln Center. The music is recorded – how great it would be to hear it live. Boykin deploys a large cast (21) that includes six members of the junior troupe, Ailey II. From a theatrical perspective, the most beguiling aspect is her ability to suggest a kind of multigenerational society onstage, aided by her imaginative costumes evoking people from everyday life: waitresses, middle-class dowagers, kids, laborers. What is less clear is why every group is dressed up in a different color, like candy-colored chess pieces. Each section of the piece has a mood, reflected by Jackson’s orchestration featuring bebop-y sax, clapping music, cello and piano. Each is vaguely related to this or that passage from the writings of Martin Luther King, as declaimed by Hamilton’s Leslie Odom in voiceover.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

There are scenes of processions, prayer, flirtation, games, violence, and exclusion, all peppered with pure dance. In and out of this world floats Matthew Rushing, sermonizing with his upper body and hands. Short passages of King’s speeches waft over the proceedings: “I must be measured by my soul, the mind is the standard of the man,” and the Shakespeare quote “Love is not love which alters when alteration finds.” The quotes are pithy; perhaps it’s best to think of them as part of the dance’s rhythm, especially as delivered by Odom’s sing-songy, spoken-word style. The main problem with the work, though, is that it rambles on, somewhat at odds with itself: is it serious or is it light? The King figure never acquires much gravitas. Even the violence feels playful. Boykin can’t seem to resist her own high spirits. This r-Evolution is best enjoyed for its 1950’s idiom, its vibrant music, and its essential generosity and buoyancy of spirit.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

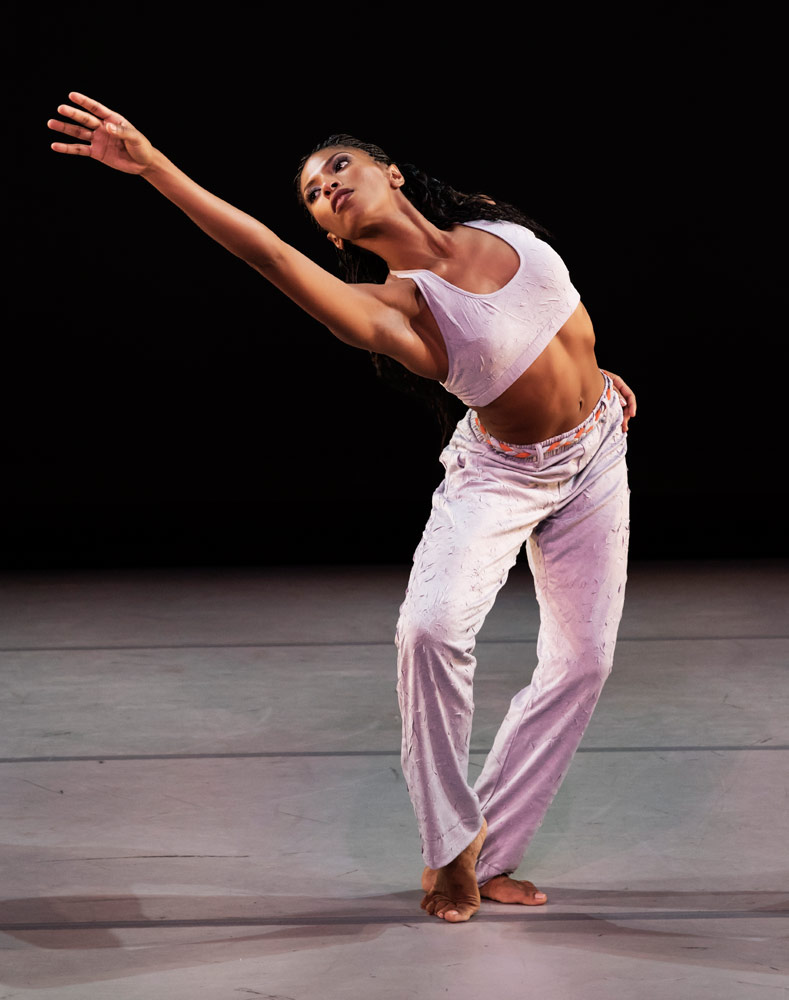

Untitled America, on the other hand, is almost doggedly steady in its intent and mood. Abraham has taken on a weighty subject, and treats it with respect and seriousness. Over three seasons – one section premiering each season – he has created an ode to the suffering of African American families who have lost family-members to the prison system. Images of bound hands and death recur, within a dark landscape in which bodies appear and disappear out of the murk. Often they stand with their backs to the audience, the better to show their bound hands. Voices, drawn from interviews, describe feelings of loss and powerlessness: “I can’t change the past,” “my sentence was 6-12 years,” “I miss belonging to someone.” The mood is grim.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Untitled opens with the dancers in a line, at first advancing in unison, raising their arms as if in surrender. Then, individual dancers kneel, fall, and stand up. Later, a tortured pas de deux, set to a work song, depicts a couple in conflict; a shot rings out, the man falls. Another dancer, Jamar Roberts, gently touches the floor. Eventually, single portraits begin to emerge, characterized by Abraham’s fast, detailed, spiraling, somewhat twitchy vocabulary, full of spins and leaps. There is something reminiscent of martial arts in his style. The problem is that, for all its virtuosity, Abraham’s choreographic idiom isn’t particularly expressive. The piece begins to lose focus. A final tableau, set to Laura Mvula’s song “Father, Father,” manages to wrest it back, raising the emotional temperature. A woman, and then a man, perform solos of almost marionette-like brokenness. Untitled has a powerful ending and a sharp opening – perhaps in later seasons Abraham might tighten up the middle.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

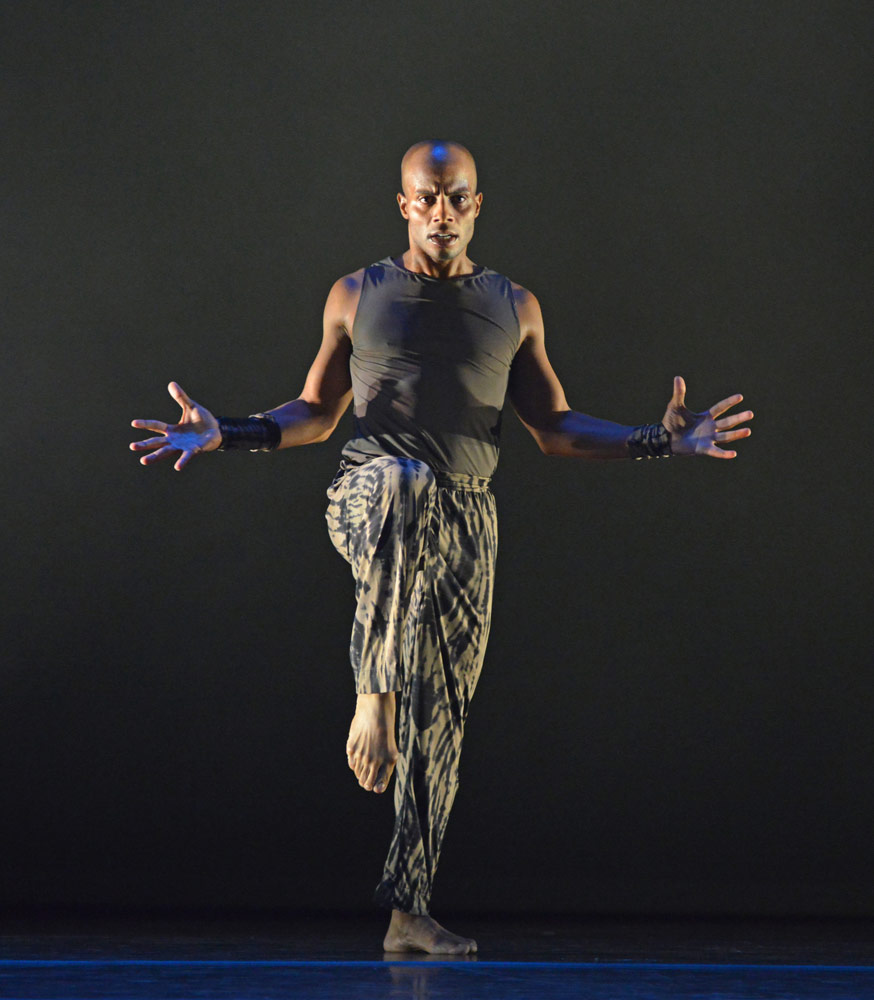

Ronald K. Brown’s Four Corners was performed on both evenings, by different casts. It’s not surprising that this work, from 2013, is a mainstay of the repertory. Brown’s use of the whole body, particularly the back and arms, gets to something deep inside us; the movement is sensual, grounded, explosive. Just as impressive is his mastery of stage space; dancers emerge and disappear from the wings, like migratory birds or the tides. You barely notice them coming and going. The flow of bodies hints at the possibility that even beyond the curtain, the dancing continues, as naturally and continually as waves in the ocean.

You must be logged in to post a comment.