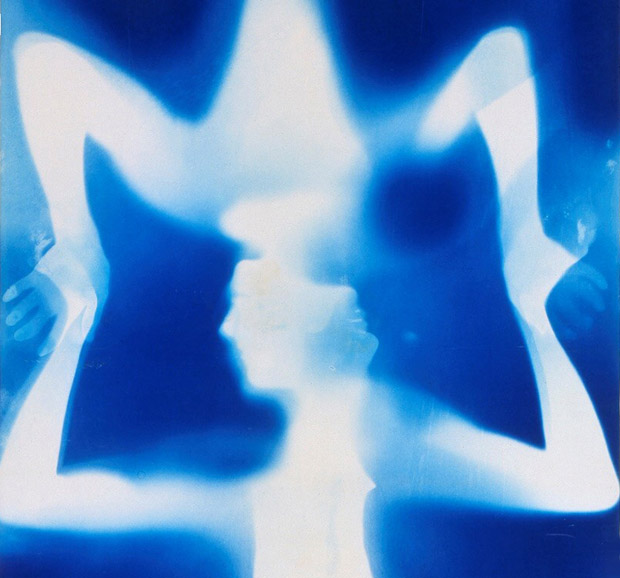

Monoprint: exposed blueprint paper.

209.6 x 92.1 cm, Private collection.

© Robert Rauschenberg. (Click image for larger version)

Robert Rauschenberg Exhibition

London, Tate Modern

1 December 2016 – 2 April 2017

Exhibition details

www.rauschenbergfoundation.org

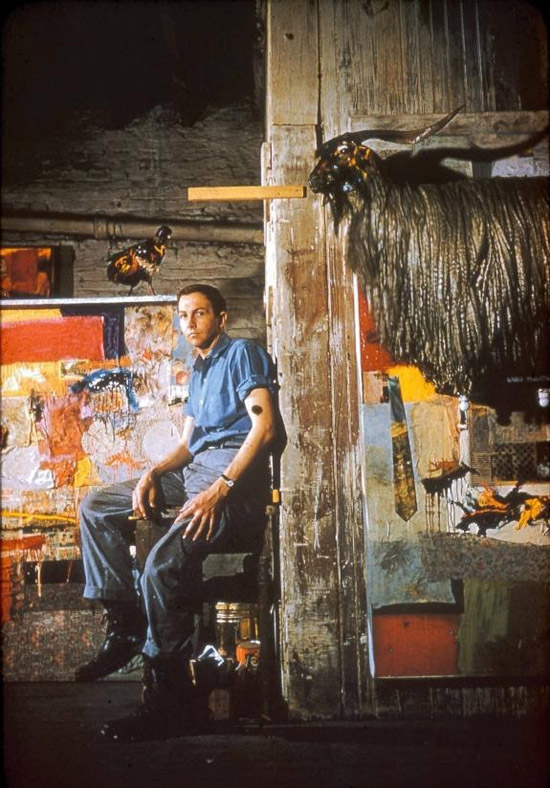

The Tate’s retrospective of Robert Rauschenberg’s six decades of work claims to be the most comprehensive survey of his output since the artist’s death in 2008. Each chapter of his multi-media career is represented in different rooms, with loans that rarely travel. Among them is the stuffed angora goat surrounded by a car tyre, last seen in the UK over 50 years ago. Monogram, the title of the 1955-1959 work, is now too fragile to tour frequently from its current residence in Stockholm’s Moderna Museet.

Combine: oil, paper, fabric, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe-heel, and tennis ball on two conjoined canvases with oil on taxidermied Angora goat with brass plaque and rubber tire on wood platform mounted on four casters.

106.7 x 135.2 x 163.8 cm. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Purchase with contribution from Moderna Museets Vänner/The Friends of Moderna Museet.

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York. (Click image for larger version)

Treated just as reverentially by exhibition curators is Minutiae, Rauschenberg’s set for a 1954 Merce Cunningham piece. Cunningham commissioned it after encountering Rauschenberg at Black Mountain College, a centre for experimentation in the arts. The set, a column and free-standing panel consisting of a collage of paint-spattered canvas, fabric strips and comic-strip clippings, used to be strapped to the roof of the company’s VW minibus in all weathers between performance venues. Now given pride of place in Room 2, it can also be seen in performance in a video clip from a TV ‘Event’ in 1977.

Minutiae marked the beginning of Rauschenberg’s involvement with Cunningham’s company. Between 1954 – 1964, he also served as its stage manager and lighting designer. He called the company his biggest canvas. From a dance-lover’s point of view, there isn’t nearly enough in this ‘comprehensive’ exhibition about Rauschenberg’s many collaborations with choreographers, who included Paul Taylor, Trisha Brown and Viola Farber as well as Cunningham. (Fortunately, other galleries, such as the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, have their own dance-related collections of his and other artists’ designs.)

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York. (Click image for larger version)

Rauschenberg broke with Cunningham’s company after a fractious world tour in 1964. He moved in with Steve Paxton, the dancer and choreographer who was one of the founding members of Judson Dance Theater in New York. One of the tenets of the Judson Church movement in the 1960s was that non-dancers could not only dance in performances but choreograph as well – as Rauschenberg did. Some of his performances are documented in the exhibition in notes, black-and-white photographs and blurry video clips.

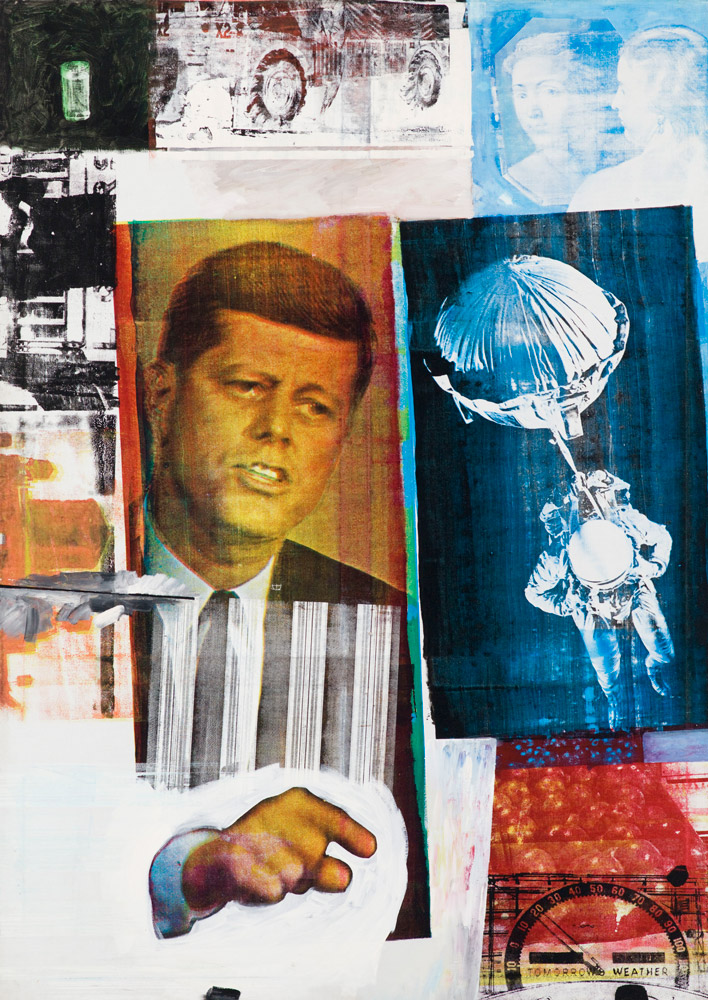

Oil and silk-screen ink print on canvas.

213.4 x 152.4 cm. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Partial gift of Stefan T. Edlis and H. Gael Neeson.

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York. Photo: Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago. (Click image for larger version)

In Pelican (1963-1965), Rauschenberg and a second man – initially Per Olof Ultvedt, a Swedish artist, then Alex Hay, also an artist – entered kneeling on an axle between two bicycle wheels. Wearing roller skates, they then circled the performance area with cargo parachutes on their backs like gigantic parasols. They swung round Carolyn Brown, a Cunningham dancer wearing a tracksuit and pointe shoes. The two men then departed as they had entered. Rauschenberg’s hand-written instructions, preserved on a sheet of exercise-book paper, are detailed enough to warrant his credit as choreographer. (More information on the Rauschenberg Foundation site).

Rauschenberg continued to perform in his own pieces (Shot Put, Elgin Tie, Map Room, Spring Training, Linoleum, Open Score, all documented in Room 7) as well as in other choreographers’ work until 1968. His contributions were not exactly dancerly: in Elgin Tie, for example, he descended down a rope into a barrel of water while a cow was led into the performance space. He began collaborating with engineers through a foundation he called EAT – Experiments in Art and Technology. One of the creations, Mud Muse, bubbles away choreographically in its glass tank, erupting in response to a recorded soundtrack.

In 1977, Rauschenberg reconnected with Cunningham and provided the set and costumes for Travelogue. A row of chairs supported upturned bicycle wheels; colourful costumes had silken panels that unfolded like peacock’s tails or lizards’ throats. In Room 8, TV monitors play a few minutes of Travelogue from a South Bank Show recording in 1980. Not on display are Rauschenberg’s later designs for Cunningham’s Interscape (2000) and XOVER (2007), both with spectacular backdrops made up of silk-screen photography and painting.

One example of Rauschenberg’s frequent collaboration with Trisha Brown’s company (1979-1994) is his set for her Glacial Decoy (1979). Slides of black-and-white photographs, taken by Rauschenberg himself, flicker in sequence behind dancers in semi-transparent pleated costumes as the dance comes and goes, starting with the outside edges of choreography that is finally filled in centre-stage. Brown’s Set and Reset (1983), with his designs, is to be performed in Tate Modern’s Tanks on 27 and 28 January 2017 by members of her company. (A version of Set and Reset/Reset is currently in the repertoire of Candoco Dance Company.)

Set and Reset has slippery costumes that look rather like newsprint, patterned with monochrome images of New York streets. A montage of black-and white film footage is projected onto structures overhanging the dancers, who cluster and tumble to Laurie Anderson’s mesmerising ‘Long Time No See’.

Though Rauschenberg’s designs have no apparent connection with the dances they accompany, and even compete for the audience’s attention, they have become inescapably part of the experience of each work. Cunningham’s Summerspace is the one with the pointillist dots on the costumes and backdrop; Taylor’s 3 Epitaphs is the one with the simian performers whose shrouded heads glint with mirrors; Brown’s Astral Convertible has metal stands with mini spotlights on them. Rauschenberg was endlessly inventive, curious about how a theatrical setting could transform objects and actions into a work of art.

The Tate Modern exhibition provides a gallery setting, not a theatrical one (until the Tanks performances at the end of January). Printed information is solemn, even reverential, missing the absurdist sense of fun and surprise that characterised Rauschenberg’s experiments – especially those involved with dance. But it’s a joy to see the range of his imagination in the works, small and enormous, in the 11 rooms of the exhibition. After 2 April 2017, it will travel on to New York and San Francisco Museums of Modern Art.

You must be logged in to post a comment.