© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

The Illustrated ‘Farewell’, The Wind, Untouchable

★★★✰✰

London, Royal Opera House

6, 9 November 2017

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.roh.org.uk

The Royal Ballet’s latest triple bill is a test of the company’s versatility as classical ballet dancers, dramatic actors and contemporary dance rebels. Artistic director Kevin O’Hare is commissioning choreographers who want to make use of what the Opera House can offer; he’s not setting out to declare where ballet ought to be heading and he’s not playing safe.

Arthur Pita has seized the opportunity to operate on a grand scale. For The Wind, he has put three huge wind machines on stage, along with vast swathes of fabric. He and his collaborators have created a gothic Western ghost story, in a prairie setting that has nothing in common with Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo or Oklahoma ballet. At a first viewing, I thought he’d over-egged his dance-theatre drama; at a second viewing, I enjoyed his extravagant imagination and vivid awareness of absurdity.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Why not add two ghosts to a melodrama based on Dorothy Scarborough’s 1925 novel and Victor Sjöström’s 1928 film, both titled The Wind ? A woman is driven to insanity by a hostile force – and ballet is very good at spirits and madness. Letty Mason is a young woman who has to leave the comforts of East Coast Virginia for cattle country Texas in the 1880s. The settlers have taken over land they consider barren, driving out the indigenous inhabitants.

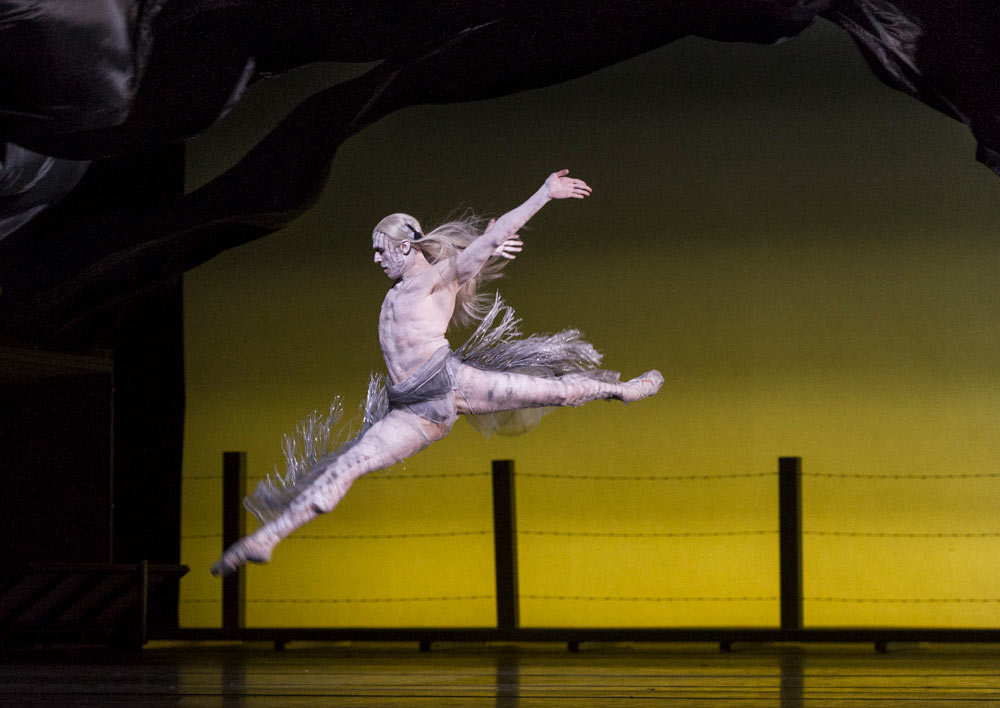

Pita’s ballet starts with an angry ancestral spirit (Edward Watson), a ghostly Comanche warrior patrolling his territory. He is the wind made visible, scouring the prairie and intimidating the ranchers. The second ‘ghost’ is the presence of a displaced woman (Elizabeth McGorian), brought up by the Comanche tribe, who tries to warn Letty that no good will come of her arrival in the pioneer community.

Naïve Letty is hardly made welcome by the tough womenfolk, who fear her effect on their men. One of many powerful images is that of the cowpunchers in their hats and chaps arriving in silhouette against a barbed-wire fence. They’ve come not for a hoe-down but a bonding ritual involving a kind of maypole surmounted by a bull’s skull. Its ribbons flutter in the ever-present wind that tugs at the women’s clothes and hair. Its sound is recorded in Frank Moon’s score, which goes from whining guitar strings to full-blown orchestral thunder.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Enter a devil-figure in a black hat, arriving on a railroad pump trolley. He is bad Wirt Roddy, a cattle buyer (Tom Whitehead in the first cast, Matthew Ball in the second). He spots Letty as a fresh young heifer, kissing her hand possessively, but is pushed away from her by one of the cowboys, Lige Hightower (Thiago Soares or Tomas Mock).

A storm intervenes, a banner of black silk heralding the return of Watson as a shaman foretelling disaster. His gestural language is emphatic, though the choreography for his ‘tribal’ pounding is underwhelming.

The story now becomes too compressed. We know nothing about the Hightower character before Letty is obliged to marry him. Their wedding, swiftly conducted by the local pastor (Reece Clarke), is an absurdist evocation of a Chagall painting of newlyweds. Letty floats in Lige’s arms, her veil streaming against the night sky. Moon’s music becomes a curdled version of Aaron Copeland’s Appalachian Spring.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

There’s not enough time to find out what Letty makes of her wedding night, or her husband, before he goes off to work. Is he kind? satisfactory? inadequate? Left alone, she becomes wildly agitated, tormented by the wind forever blowing the door of her bedroom open. (Two of the wind machines, resembling agricultural threshing machines, have been moved close to her homestead.)

Enter Wirt Roddy in his bad black hat and sinister coat. The wind – or Letty’s own sexual longing – hypnotises her by sending the overhead light swinging. Roddy succeeds in locking the door and having his ruthless way with her. After a blackout, we see the ghostly Comanche woman agonising as though remembering her own rape. Letty, too, is appalled at what has happened to herself as a new bride.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

When Roddy treats her with contempt, she grabs his gun and shoots him dead. Time and the wind have stood still. Watson materialises to claim her as a future spirit, whirling around her and sweeping her off her feet. When he vanishes again, she is driven into a frenzy by the demonic wind machines, hurling herself around the stage, rolling and tumbling, spinning and kicking on pointe. A huge sheet of silk threatens to overwhelm her and the corpse of her rapist. In silence, she stumbles away into the distant prairie. The ambiguous ending was marred at the second performance by the darkness descending too soon.

As Letty in the opening cast, Natalia Osipova went convincingly berserk at the end – a lonely, isolated woman finding the strength to defy the man who violated her. Francesca Hayward in the alternate cast was less overtly defiant, more of a bewildered innocent overtaken by a force beyond her control. Both are shattering interpretations, made even more so by having to resist the relentless thrust of the wind machines.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Pita has stated that he wanted the wind, ‘the cause of it all’ in Scarborough’s haunting novel, to have a physical presence on stage. The mechanisms, though, are too literal: windblown fabrics could have been sufficient, along with howls and whines in the score. The timeline is too condensed to establish whether the cause of Letty’s prairie madness is external or internal, supernatural or psychological. In a fuller account of the story, Pita might be able to round out the other characters and the community in which Letty loses herself. Although the two casts of dancers are very different, the men are almost indistinguishable, faces hidden by hats and moustaches. If The Wind is to survive, Pita should be given the chance to expand his ideas and reconsider his staging.

Twyla Tharp has returned to her 1973 ballet, As Time Goes By, in order to choreograph all four movements of Haydn’s 45th symphony, known as the ‘Farewell’. She has mounted the fourth and fifth movements for several companies (including her own) over the years. For the Royal Ballet’s commission, she has added a duet to the first two movements to showcase principal dancers Sarah Lamb and Steven McRae, and called the result The Illustrated ‘Farewell’. Her new choreography is a fresh gloss on Haydn’s symphony, contrasting her approach to the music then and now.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

When Frederick Ashton created Rhapsody as a showcase for Mikhail Baryshnikov in 1980, he is supposed to have asked the dancer to bring his best steps. Tharp appears to have done the same for McRae, challenging him to move ever faster, cover more ground and embellish his fabulous pirouettes. He is required to partner Lamb gallantly, while competing with her in virtuoso responses to Haydn’s musical statements. If she does a teetering run on pointe, he has an even speedier go on demi-pointe; if she plunges into a deep arabesque penchée, he does the same with an added turn en seconde.

It’s a game of matching skills, nonchalantly carried off. They dart in unison, then in counterpoint; they separate for sassy hip and shoulder wiggles, small beaten steps and flying jetés, then link together in a ballroom waltz. They take a bow after the fiendishly fast movement in order to catch their breath, then launch into a courteous minuet, taking it in turns to occupy centre stage in skids and slides. In a kind of parody of a classical pas de deux, they separate only to come together, as if they can’t bear to be apart any longer. They walk off triumphantly together, arm in arm.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Then it’s the turn of the youngsters, dancing with each other rather than at the audience. Maya Magri introduces the third movement in silence, as though listening to music only she can hear, until five of her friends arrive as the orchestra joins in. The intricate sextet involves constant changes of partner, with Magri (in brown) representing the main theme. Yet more youngsters enter, with Joseph Sissens outstanding in white. What looks like anarchy turns out to be highly organised, as the group of 17 overlap and coalesce into a unit.

Sissens has two female guardian angels, with Anna Rose O’Sullivan the constant one. He is confronted at one point with McRae standing by to watch him, as if his mentor or ancestor. Dancers come and go, but not as pointedly as the musicians, who leave one by one, blowing out their candles (in Haydn’s time) until just two violinists remain. Tharp has slotted in the starry pair of principals as reminders of an earlier age, a couple who’ve seen it all before. They dance together on high, echoing Sissens’s last moments with O’Sullivan until he is left alone, still dancing, as the curtain falls. Tharp has sentimentalised an otherwise poignant sense of continuity by not letting Sissens own the ballet’s conclusion.

The Illustrated ‘Farewell’ makes a joyous start to the triple bill, showing how witty and civilised dance and music can be. The last piece, Hofesh Shechter’s 2015 Untouchable, doesn’t deserve its revival. It has been outclassed by Crystal Pite’s Flight Pattern on a similar theme of anonymous people flocking together – outcasts, refugees, insurgents. Shechter’s horde of irregulars keep reassembling, veering between accepting that unity is strength and rebelling against conformity.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Individuals who try to leave the ensemble, like the musicians in Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ symphony, are threatened with a fearful fate. They are reabsorbed into the horde, dancing together as a tribe or a corps de ballet. How they move is not particularly challenging, in spite of Shechter’s belief that his signature simian loping is a stretch for ballet dancers. A recorded chant of ‘Nigel Farage’ now sounds even sillier than it did two years ago. Put the whole thing away as a dated commission that never merited its place in the repertoire.

You must be logged in to post a comment.