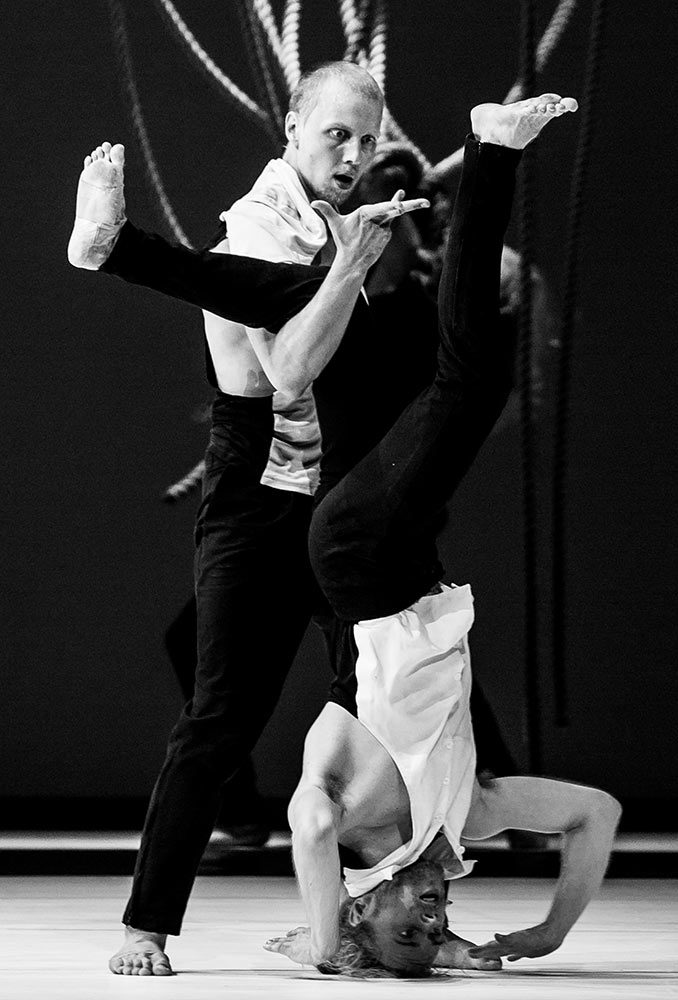

© Mikki Kunttu, courtesy Tero Saarinen Company. (Click image for larger version)

Some dance can be really thought provoking and that seems to have been the case with Tero Saarinen’s Morphed – at least for Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer who recently caught up with the work at the Joyce in New York.

Tero Saarinen Company: terosaarinen.com

This autumn we were fellows at the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University, a “think tank” that enables artists and scholars to get on with their projects while enjoying each other’s intellectual company and ready access to Manhattan’s cornucopia of dance.

One of the performances that most intrigued us was the New York showing of Morphed by Helsinki choreographer Tero Saarinen, whom we met when staging our reconstruction of Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring at the Finnish National Ballet way back in 1994. No sooner had Tero started rehearsing as a Slavic youth in our production than he had the chance to study Kabuki and Butoh in Japan. Off he went, of course, to add Japanese stillness and another sort of strangeness to his choreographic tool kit. Since then we’ve never lost touch with him. And all the while we have watched with interest, live and online, the evolution of his work.

© Mikki Kunttu, courtesy Tero Saarinen Company. (Click image for larger version)

So, what did he show us and tell us in Morphed and how do we suppose he got there? Morphed takes place in a three-sided enclosure of many long thick ropes that are hung from high pipes at the sides and back of the small but mighty stage of the Joyce Theater. Do these pliable hemp bars keep the all-male cast entrapped onstage? Are there a hundred Rapunzel’s overhead, letting down their braided hair? And, if so, is there an implied female presence in this singularly masculine world? Or is this a seductive curtain that opens into some seraglio on Manhattan’s Lower West Side?

At the outset we were pleasantly mystified. Then a kind of anxiety set in as the seven hooded men broke into relentless military formations, curtailing Speke Salonen’s music in lock-step rhythms that tightened the heart. This scene could be a portrait of men as soldiers. Or prisoners. Or, less specifically, a shout about the restrictions that gender clichés (like martial drills for men) impose on individuals. The Salonen Concert étude for solo horn is well-served by Saarinen’s choreography which holds its own as a set piece. But what it means seems to shift once juxtaposed to the dances that follow.

The next piece – the work does seem to evolve in distinct parts that invite comparison – focuses on opposition. These strong but supple men, all of whom look like they could handle a street fight, pull each other off balance, manage to multitask while standing on one leg and seem to revel in their testosterone. These displays command attention and attract through their dynamism. They reminded us of the way Finnish male dancers relaxed between rehearsals: arm-wrestling, sparring, tripping each other and tumbling in bursts of combative play and pent-up energy. Morphed captures that vitality yet seems to grope beneath the surface to confront the illusions behind cultural posturing of this sort.

© Darya Popova, courtesy Tero Saarinen Company. (Click image for larger version)

But then, often through the intervention of the surrounding ropes, the images read differently. The horrors of the nightly news suddenly take shape before our eyes: men in some world apart are bound by cords for a dreadful destiny. Are we watching them on a television or computer screen, at a safe remove, treating reality as fiction for our own peace of mind? In the midst of the opposing forces and frictions in Morphed there are truly unsettling moments. A rope is a noose. Hooded figures return. Some “Klannish” kind of organisation seems to threaten.

Sometimes the ropes wrap a figure like a mummy. Sometimes they are thrown in a gust of liberation, as though a wind has cleansed all the accumulated images and we start again. Garments come off. Men in monochromatic trousers, waistcoats, collars and such could be half-dressed gents in evening gear. Or ambiguously stripped-down businessmen who have metaphorically and practically lost their shirts.

The protective function of clothing is undermined. That seems to be a statement about male consciousness. Despite the vitality of their movement, these men project a sense of disintegration and incompleteness.

© Heikki Tuuli, courtesy Tero Saarinen Company. (Click image for larger version)

Resolution comes, however, mostly through the music of Salonen’s Violin Concerto, the final section of the piece, and also through the centrality of the dancer Ima Iduozee (Finland’s breakdance champion) who wraps himself in Saarinen’s movement and seems to draw the ropes and the men around him into a swaying rhythm of male sensuality and human harmony. Even then though, a sense of loss prevails. The ropes hang heavily like massive violin strings in deep adagio.

After we saw Morphed at the Joyce we met up with our colleague Wendy Perron, a post-modern performer and choreographer who has written about dance for several decades. “It seems to be a genre right now,” she said, referring to the proliferation of all-male pieces.” Then she added, “My thought is that most ballets feature women, so some choreographers are trying to balance things out by making all-male pieces.” Together we recalled the gamut of men-only works from Ted Shawn and José Limón through Hans van Manen, John Neumeier and more recently Josh Beamish as well as mostly male works by Stanton Welsh, Alexei Ratmansky and Saarinen’s compatriot Jorma Uotinen. Perron went on to connect the rise of all-male dance companies like MadBoots, the Randy James group 10 Hairy Legs, and the “Trocks” who have perenially crossed gender boundaries. And, of course, there are the BalletBoyz in the UK.

© Darya Popova, courtesy Tero Saarinen Company. (Click image for larger version)

In dance history, folk culture has usually opted for a male/female style split. Folk dances featuring men in their potency and sheer physicality can be seen as the bedrock of balletic virtuosity in many parts of Europe, and elsewhere, for that matter. But the current phenomenon of male dancing does seem to be in seismic shift, equal to the one that changed ballet repertoire in Nijinsky’s blaze of glory and again in the heyday of Nureyev.

Tero Saarinen’s Morphed presents a dance of psychological and sociological complexity that does not need to be explained but explored. Soul shifting is a field of action where this choreographer from the frozen north warms to his subject. In the future Morphed may stand as a new lyrical direction in the genre of “brothers are doing it for themselves”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.