© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

For more on Festival Diaghilev. P.S. see Jann Parry’s “Dipping in to the 8th International Festival of Arts ‘Diaghilev. P.S.’ in St. Petersburg“

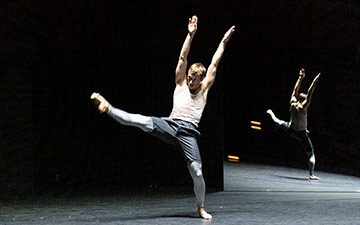

Ballet de Lorraine at the International Festival of Arts ‘Diaghilev. P.S.’

Relâche

★★★★★

St. Petersburg, Tovstonogov Bolshoi Drama Theatre

1 December 2017

ballet-de-lorraine.eu

www.diaghilev-ps.ru

The Ballet de Lorraine, based in northeastern France, was one of the companies invited to the 8th Diaghilev P.S. festival in St Petersburg to show how dance experimentation had spread internationally in the century since Diaghilev formed his Ballets Russes. The French company’s programme included its reconstruction of Relâche, first performed by the Ballets Suédois in 1924-25. It had caused almost as great a scandal as the 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring in the same Théâtre des Champs-Elysées.

©/courtesy International Festival of Arts “Diaghilev. P.S.”

The first and only Dadaist ballet, Relâche had just 13 performances and was never revived. Its expense helped bring about the closure of the company, run by Rolf de Maré, who was competing with the Ballets Russes in Paris in the 1920s. De Maré’s interest was not so much in dance as avant-garde performance in collaboration with artists. Once the productions were no longer performed, they disappeared, leaving only traces in archive collections. Although other works from the Ballets Suédois’ repertoire have been reconstructed, mostly for the Royal Swedish Ballet, Relâche had remained a rarity, until the Ballet de Lorraine undertook it in 2014. (A version of Relâche by Moses Pendleton for the Paris Opera Ballet, 1979 and the Joffrey Ballet, 1989, was in his own choreography, not a scholarly reconstruction.)

Petter Jabcobsson, artistic director of the Ballet de Lorraine since 2011, had long been fascinated by Relâche. British ballet goers might remember him as a principal dancer with Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, 1984-1993. He later became artistic director of the Royal Swedish Ballet, 1999 – 2002. He discussed then the possibility of remounting Relâche with Bengt Häger, distinguished Swedish dance writer, archivist and doyen of dance institutions. It was only after Häger’s death in 2011 that Jacobsson succeeded in retrieving from one of his archives a handwritten piano reduction of Erik Satie’s score for Relâche, with detailed annotations of the dancers’ actions.

‘Bengt had told me that there wasn’t much choreography when he researched the ballet for his book about the Ballets Suédois’, Jacobsson says. ‘The dancing was just a send-up of vaudeville routines. The Dadaist point was that nothing really happened in the “ballet’. There was no story, just unrelated events. And there was film at the beginning and in the middle. This was new at the time, like the performers coming onto the stage from the audience, where they’d been sitting in the stalls.’

Jacobsson set about reconstructing Relâche as closely as possible in order to evaluate its impact on the evolution of theatrical dance. ‘We’ve found out everything we can to show what Relâche must have been like at the time. So much of what seemed new in the 1960s and 1970s actually occurred much earlier’, he says. ‘Happenings had already been done, moulds had already been broken. We know we can’t recreate the past but we can help it come alive again.’

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

When he and his team started searching for information in Stockholm, Paris and London, they encountered Carole Boulbès, a French art historian who is a specialist in Dadaism and Surrealism. She was particularly interested in Francis Picabia, the driving force behind Relâche, and his circle of friends and colleagues: Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Erik Satie and the young film-maker René Clair. Her research fed into the Ballet de Lorraine’s production, which in turn provided material for her fascinating book, Relâche – dernier coup d’éclat des Ballets Suédois (2017). She sets Relâche in the cultural context of its era, chronicling avant-garde experimentation in France in the early decades of the 20th century.

What was so radical about Relâche? First of all, its title, which means in French theatres that a performance will not take place. Coincidentally, the opening night had to be cancelled because the Ballets Suédois’ leading dancer, Jean Börlin, was ill. The cancellation was assumed to be a Dadaist joke. When the premiere took place a week later, the set for the first act proved a challenge for audiences as well as for the technicians who had installed it: a luminous wall of hundreds of electric bulbs reflected by metallic disks. The intensified light dazzled the eyes of spectators. A journalist (and Picabia himself) warned theatre-goers to wear dark glasses, as well as ear plugs for Satie’s music.

A still from Ballet de Lorraine Relâche teaser video. (Click image for full version)

Boulbès ascertained that the lighting rig was installed by a well-known firm, Paz and Silva, responsible for most of the electric illuminations in Paris (including the Eiffel Tower). The Ballet de Lorraine’s spectacular set, created 80 years later, needed 420 bulbs – and had the advantage of computerised technical equipment.

At the start of the performance I saw in St Petersburg, the wall was shielded by a screen on which a film was projected of members of a 1924 audience. The silent film was L’Inhumaine, in which the well-dressed audience of extras at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées included Satie, Man Ray and Picasso. The film extract then changed to René Clair’s brief sequence for the opening of Relâche, in which Satie and Picabia jump up and down with a canon before shooting it at the audience. The projected screen vanishes.

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

In silence, an elegant woman wearing a green velvet opera cloak emerges from the stalls to join a uniformed, moustachioed fireman on stage, both of them smoking cigarettes. The woman was originally Edith de Bonsdorff, a leading dancer with the Ballets Suédois. The role was taken by the Ballet de Lorraine’s Elisa Ribes, supremely confident in confronting the audience and the performers on stage. Enter a man in evening dress seated in a wheelchair tricycle. He was Jean Börlin (Jonathan Archambault). Not only was it audacious to have a star dancer enter in a wheelchair with a balloon attached, but it also served as a reminder of the numerous disabled men on the streets of Paris after the First World War.

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

The woman removes her cloak to reveal a sparkling silver flapper dress. Once the music starts, she vamps and dances with the man, no longer disabled, before eight dandies in evening dress erupt from the stalls. They prance around and permit the woman to walk over their backs in her high-heeled shoes. She has performed a fairly modest strip tease – a reference, possibly, to the artwork by Duchamp known as The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even.

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

Satie’s score used popular songs that were known to have obscene lyrics when sung by soldiers. His contribution was derided by critics as pornographic music, unfit for the theatre. He also composed the film score for Entr’acte, the surrealist 18-minute film by René Clair projected between the two acts. The detailed scenario was by Picabia, who envisaged Relâche as a ‘ballet-cinema’, with members of the Ballets Suédois as participants in the 18-minute film.

Jacobsson is proud that Entr’Acte has at last been seen in its original context in a dance work, instead of regarded as a cinematic museum piece or posted in isolation online. The film and its score have been endlessly analysed by scholars as the first surrealist collaboration by renowned creators.

In so far as there is a narrative in the film’s disjointed proceedings, it involves a hunter (Jean Börlin), who falls off a Parisian roof after being shot by Picabia. The dead man is given a formal funeral, with his wheeled coffin being drawn by a camel. The cortege is made up of dancers bounding along behind in Monty Pythonesque silly walks. The coffin breaks loose and hurtles through the countryside, chased by the mourners, to a Luna Park Big Dipper. When the coffin finally crashes, Börlin climbs out, smiling, and makes his followers vanish with a wave of his magic baton. In the last moments, Börlin bursts through the paper announcing Fin, The End, protesting that the show is to continue. Rolf de Maré slaps and kicks him, and the intact announcement of Fin rematerialises.

Entr’Acte is a Dadaist farce, with cameo appearances by Picabia and Clair, as well as by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, both playing chess on a rooftop. A recurring motif of a dancer photographed from underneath, showing her bloomers and suspenders as well as her billowing skirt, features Inge Friis of the Ballets Suédois. In one shot she wears a false beard, a reference to the transvestism in the music halls at the time. Satie’s relentless, repetitive film score seems intended to exasperate – which it still succeeds in doing,

Jacobsson says that when the Ballet de Lorraine performed Relâche on tour in France and China, audience members hated the film and the music. ‘People walked out, demanding their money back. They said they came to see dancing, not an absurd black-and-white film with annoying music. In one town in France, St Etienne, people stood up and booed and shouted. I felt I was experiencing what probably happened at the premiere of Le Sacre du printemps in 1913 – which is, of course, exactly what the Ballets Suédois intended.’

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

The show then continues with a second act on stage, against a black backdrop painted with slogans in French, some celebrating the creators, some insulting the audience: ‘If you don’t like it, you can piss off. Or you can buy whistles for part two at the box office. Do you prefer the ballets at the Opera (de Paris)? Poor you. ‘

Throughout the second half, the grandly-uniformed fireman imperturbably pours water from one bucket into another. Two nurses (one bearded) carry the leading lady reclining on a stretcher. She steps off and wriggles into her glittering silver dress. Now it’s the turn of the men to strip down to white bodysuits dotted with reflective circles. They perform basic circus acrobat routines as the woman collects their discarded clothes in a wheelbarrow. Enter a sinister hooded figure in black (Börlin), glittering with mirrors. (Paul Taylor devised a somewhat similar outfit for his Three Epitaphs decades later.)

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for full version)

Börlin monopolises the woman, to the distress of one of the acrobats, his rival, the dancer Kaj Smith (Willem-Jan Sas), who buries his face in his hands. Nothing much else happens. The woman puts on her cloak and leaves through the audience, waving goodbye. Apparently, as the audience left the Théatre des Champs-Elysées, a man dressed as rat (or a mouse) appeared in front of the curtain, did two petits tours and ran off. Maybe the message was an old adage: All that fuss, and the mountain gives birth to a mouse.

The Ballet de Lorraine’s audience in St Petersburg applauded enthusiastically. To Jacobsson’s disappointment (he said), only a few people had walked out: Diaghilev Festival dance-goers have become accustomed to being disconcerted. Russia, however, didn’t experience the American revolution in post-modern dance in the middle of the last century, promulgated by Judson Church performers and the Grand Union collective. Their manifestos, saying no to virtuosity and narrative conventions, insisting that dance could be anything and happen anywhere, were remarkably like the Dadaists’ defiant proclamations. These innovations, savagely criticised at first, were eventually absorbed into the trend-setting mainstream. Relâche today is no longer outrageous – but it is vastly enjoyable and well worth reviving.

You must be logged in to post a comment.