© Helen Maybanks, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Giselle

★★★★★

London, Royal Opera House

19 January 2018

www.roh.org.uk

There’s a world of difference between the wilis of Giselle and the sylphs of La Sylphide, even though both inhabit Romantic ballets of the mid-19th century. English National Ballet’s sylphs (at the London Coliseum earlier this month) are sunny woodland spirits, enjoying the daytime visit of a besotted man until it goes horribly wrong. The Royal Ballet’s wilis are killers, seeking revenge on any man who enters their moonlit territory.

The Royal Ballet’s corps are drilled into preternatural obedience to their queen, Myrtha. At the start of their midnight ritual, they are made anonymous by the veils covering their heads and shoulders, although two have names. Zulme and Moyna were originally an odalisque and a bayadère, prominent among a throng of ghostly multinational maidens, all dead before their wedding day. Over the years since 1841 the wilis have lost their individuality, merged into a vindictive phalanx of phantoms.

The decision that any ballerina in the role of Giselle must make is how far the doomed heroine has become a wili. In Act I, Giselle is a peasant, in love with a duplicitous nobleman, Albrecht. Heart-broken, she kills herself with his sword. In Act II, she is initiated as a well-qualified wili by Myrtha, who requires her to join the sisterhood. Giselle defies her in order to save Albrecht from certain death.

© Helen Maybanks, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Marianela Nunez, opening night Giselle, retains her humanity in Act II, rather than succumbing to the wili imperatives that overtake some Giselles (particularly Russian ones). Because Nunez has such immaculate control as a dancer, her Giselle does not appear subject to a force beyond herself, compelling her to lure Albrecht into dancing until he falls exhausted. She does, however, have seemingly supernatural powers: she can hold any pose as long as she chooses, power her flights across the forest floor, tuck her feet daintily under her long skirt in sublime entrechats en arrière and appear to float in Albrecht’s arms.

Because Nunez doesn’t have the frail Romantic line of the back of the neck into the shoulders, her account of Act II is a personal one, making the most of her strengths. Her intrepid Giselle saves Albrecht because her love is more powerful than his remorse, more powerful than Myrtha’s commands, even though Tierney Heap’s Queen of the Wilis is implacable until defeated. (She could soften her pointe shoes, to land as silently as Nunez does.)

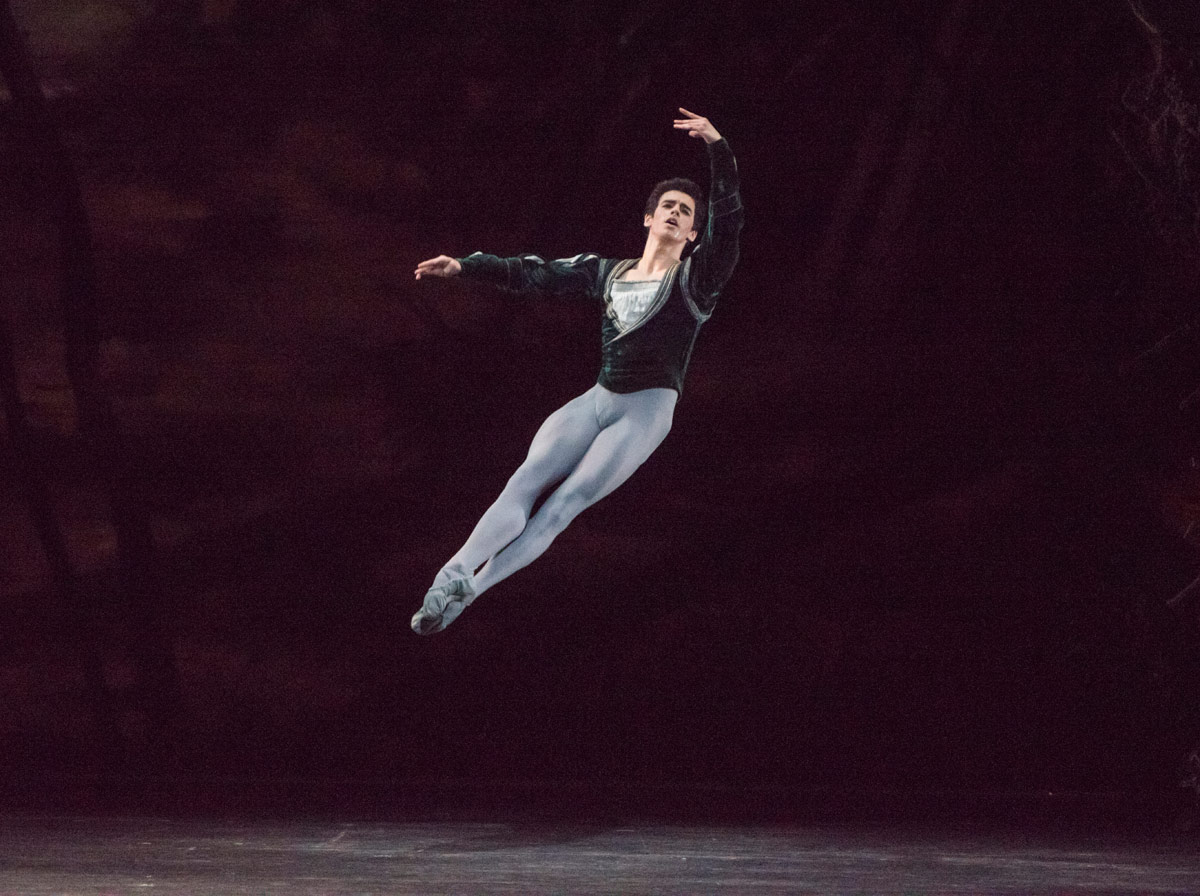

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Federico Bonelli’s Albrecht is a fine-drawn aristocrat, genuine in his repentance. He is aware that in betraying Giselle, he has destroyed his self-respect. His dancing in Act II, though well executed, is without bravura embellishments; he is truly at the wilis’ mercy. In Act I, he shows good manners in his interactions with the local peasantry, joining their dances at Giselle’s invitation without showing off. He is love-struck, lingering in his embraces with her as though entranced.

Nunez is guileless as the local beauty, infatuated by his charm. She responds to him far more eagerly than to her rough-hewn suitor, Hilarion (Bennet Gartside, convincing as always), who feels entitled to claim her as his intended. Nunez, about to celebrate her 20th year with the company, has achieved the perfect balance in Act I between youthful naiveté and a highly sophisticated technique that enables her to accomplish anything she wants. In her solo for the courtiers, she pauses on the music as though asking whether she’s doing all right; she downplays the diagonal of hops on pointe without soliciting applause, then whirls in piqué turns, overcome with excitement.

© Helen Maybanks, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

As her mother, Berthe, Elizabeth McGorian is haunted, wary of her daughter’s wilfulness and of the handsome suitor she knows little about. She’ll be broken by Giselle’s loss of reason and painful death. In the mad scene, Nunez doesn’t indulge in pathos. When she stumbles upon Albrecht’s discarded sword, she goes feral, seizing it gleefully as a lethal weapon. She charges her way through the bewildered assembly of peasants and courtiers, shoving them aside until she comes briefly to her senses. She dies in Albrecht’s arms at the end of Act I, as she does in Act II, becoming a corpse as her spirit fades away with the dawn.

Peter Wright’s 1985 production for the Royal Ballet has had many interpreters, all subtly or extravagantly different. Nunez is amongst the finest, a perfectionist who seems realistically earthy as a country girl who loves dancing and ethereal as her defiant spirit. The first night of this revival fielded an exemplary cast, from the ranks of the corps to the soloists in the pas de six, led by Yasmine Naghdi and Alexander Campbell, who are making their debuts in the leading roles during the season. With dancers like these, Giselle survives triumphantly as the essential Romantic ballet, stirring emotions that go beyond words.

You must be logged in to post a comment.