© Ayodele Casel. (Click image for larger version)

Evidence, A Dance Company

Come Ye, March, Den of Dreams, Dancing Spirit

★★★★✰

New York, Joyce Theater

7 February 2018

www.evidencedance.com

www.joyce.org

The Ronald K. Brown Experience

It had been a couple of years since I had last attended a performance by Ronald K. Brown’s Evidence A Dance Company. Brown is one of those choreographers who returns to a similar mode in piece after piece, so it’s easy to take him for granted. But what a powerful mode it is. His style, which is often, and not inaccurately, described as combining elements of West African dance, Afro-Cuban dance, and American club dance, is remarkable for something much deeper: the way it gives itself to the audience with a mix of pleasure, strength, and dignity. Often, the dancers seem to be performing for each other, expressing their full selves through movement, dancing with their feet, backs, arms, heads. Each dancer is a complete individual, whose personality and movement quality is on full view. Nothing is hidden behind technique.

And then there is the sophistication with which the dances are constructed. Each of the four works on the program I saw at the Joyce – Come Ye, Lessons: March, Den of Dreams, and Dancing Spirit – contained many of the same elements. The contrast of stillness and movement, speed and slowness. The complexities of rhythm, within one body and distributed amongst the dancers across the stage – at times there could be as many as four different rhythms happening at once. The seeming naturalness with which walking becomes dancing, and vice versa. The fluid use of the stage space; the ease with which Brown moves dancers on and off, so that you’re barely aware of them coming and going. Or, to the contrary, the way he can make you hyper aware of each arrival, building it into the rhythm of the dance. The absolute lack of unison (yes!). You can never get bored watching a Ronald K. Brown dance.

Each dance on the program had its own particular profile, determined in part by musical choice and casting. Come Ye, from 2002, is a moving work that alludes to the struggle for equality and dignity, skillfully binding together the experiences of black Americans (especially in the South) with those of Africans. The dancers greet each other with everyday gestures – handshakes, raised fists – that are then woven into the fabric of the dance. Nina Simone sings of prayerful Sundays in Savannah; the Nigerian Afropop singer Fela Kuti of burned homes and corruption on the African Subcontinent. A film projected toward the end of the piece drives home the point in a more literal way: we see marches in the South, marches in Soweto, a common destiny and a common fight.

In March, from 1995, two women dance to the sound of Martin Luther King’s voice intoning the words of his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, so timely that the words burn your ears. Annique Roberts watches, or walks, tracing circles around the stage, as Courtney Paige Ross dances, or vice versa. The two pray together, and at one point, partner each other in lifts and scrolling arabesques (an anomaly). They are strong, beautiful, human.

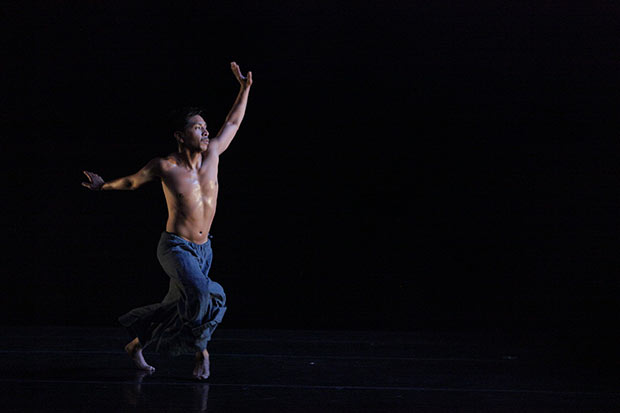

A second duet, Den of Dreams, is the only new work on the program. It is a hymn to friendship and mutual respect, dedicated to one of Brown’s dancers of long standing, Arcell Cabuag, who is also the troupe’s associate artistic director. The two men face each other, dance for each other. The way Mr. Cabuag watches Brown, even after twenty years of working together, creates a lump in the throat. Here is true devotion. They shape the movement differently – Cabuag is sharper, more aggressive, Brown more silken and relaxed – but they are like brothers, both middle-aged, both with music in their bones and hearts.

The final work on the program, Dancing Spirit, brings together the whole company, dancing to a mix of Duke Ellington, Wynton Marsalis, and Radiohead. There they are, all six full members of the ensemble, plus Brown, and three apprentices. Just ten people – and never has a stage felt more alive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.