© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

Harlequinade

★★★★✰

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

4 June 2018

www.abt.org

Harlequinade — Singing Through the Steps

The choreographer Alexei Ratmansky has unveiled his latest ballet for American Ballet Theatre: a reconstruction of Marius Petipa’s 1900 commedia dell’arte confection Harlequinade (*). Originally made for the entertainment of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, and performed at the private Hermitage Theatre, it exudes charm, warmth, silliness, opulence, all qualities one imagines a tsar might enjoy. Little did he know that the Revolution lay just around the corner. The ballet’s characters – Harlequin, Columbine, etc. – and plot are drawn not only from Italian 18th century theatre, but from the street fairs and puppet shows that took place during feast days across Russia.

Which is to say it is pure entertainment, a work of art whose entire raison d’être rests on its charm and stylishness. If you require that your art contain deeper meanings, read no further, Harlequinade is not for you. But if you delight in delicacy and craft – expressed through dance and music, then it’s a completely different story. The score, by Riccardo Drigo, is a delicious mix of salon melodies, waltzes, serenades, and dance tunes (a polka, a tarantella, a polonaise). But Drigo was anything but musically unsophisticated: a longtime conductor at the Imperial Theatres, he also wrote operas and re-orchestrated much of the second (now standard) version of Tchaikovky’s Swan Lake. He knew how to create music that enhanced the choreographer’s art. For one of my favorite passages in Harlequinade, he composes a sprightly tarantella for a large ensemble, then deftly expands it into a fugue, introducing wave after wave of dancers.

© Robert Perdziola. (Click image for larger version)

Balanchine performed in Harlequinade when he was a student at the Imperial Ballet School, after the ballet entered the regular repertory; he created his own version for New York City Ballet in 1965. As he made clear in Complete Stories of the Great Ballets, he didn’t bother with the original steps. “Who, in fact, remembers them?” he wrote, with characteristic nonchalance. But Balanchine must have remembered something, because among the steps he used for the kids in the second act ballabile there are several that appear in Ratmansky’s reconstruction as well, as do a couple of steps for Harlequin himself. The 34 kids from the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis school acquitted themselves well, forming one pattern after another: lines, curves, circles, squares, snaking processions.

What does “reconstruction” mean, exactly? What Ratmansky has done here, as on other 3 previous occasions, is return to notations jotted down around the time of the ballet’s creation, in the ballet studios of the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg. (He already did this with Sleeping Beauty, Paquita, and Swan Lake, and will soon take on La Bayadere, in Berlin.) These notated scores were written down in a system called Stepanov Notation, invented by a dancer, Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov. Stepanov Notation was abandoned after the revolution, but by then, dozens of ballets had already been notated; through the vagaries of history and auction-house sales, they ended up at Harvard’s Houghton Library, housed as the Sergeev Collection.

Just as Ratmansky spent the early-to-mid 2000’s exploring the early Soviet repertoire, since 2014 he has taken on one Petipa ballet after another. What is the point, more than one critic has asked? To some it is time wasted, and money ill spent. Ballet has changed, bodies have changed, esthetics have moved on. Besides, many of the notes are incomplete. But it seems that this, precisely is the point. Ballet doesn’t begin and end with Balanchine, nor with the versions of classical ballets offered by one company after another, often barely distinguishable from each other. These reconstructions can be an act of fertile rediscovery, of another, different beauty. A forgotten approach to composing steps, responding to music, and presenting the body. Isn’t it worth seeing what it has to offer today’s dancers, today’s audiences, today’s choreographers? I know that for me, they have revived a somewhat dormant interest in classical ballet. The steps acquire new color. They breathe.

© Robert Perdziola. (Click image for larger-version)

One can enjoy or be exasperated by the extended mime passages, of which there are many. One can’t help feeling they might have more impact in a smaller theatre. In the case of Harlequinade, as in commedia dell’arte theatre, the mime is often directed at the audience. And no, it isn’t terribly subtle, though it can be quite charming, as in an extended conversation between Harlequin – clutching a mandolin – and Columbine, who calls out to him from her balcony (silently). “What delightful music!” she exclaims, clapping her hands. “Play for me!” She leans dreamily against the balustrade. “Come down!” he gestures. “I can’t, I don’t have the key!” In the ballet’s second serenade – yes, there are two – the serenade not only strums his instrument but moves his lips as if belting out a torch song.

Such exchanges aside, the real treasures lie in the style of the dancing: full-bodied, rounded, soft, pliant, expressive, buoyant. Legs kiss each other in the air in jumps, executed while turning, moving backward, or zig-zagging across the stage. The women hop on point, tracing half-circles to show the angle of the leg and foot. Their arms complete the movement, creating a full, multi-faceted composition, pretty from every side. But these full, detailed movements of the body also have the effect of calling attention to details in the musical phrasing. The eyes are alive. Beautiful, simple images emerge: two women holding each other by the hand (overhead), supporting each other in a balance, like figures in a fountain. A woman’s torso melting in the arms of her partner, like a garland hanging over a balustrade. The dancers’ bodies sing.

© Robert Perdziola. (Click image for larger-version)

Harlequin’s plot is so whisper-thin as to be almost non-existent. In reality, it boils down to a series of set pieces. Harlequin loves Columbine; her father wants her to marry Léandre, a rich but ridiculous older gentleman. The father’s goons dispose of Harlequin by dropping him from a balcony. But a fairy revives him, and, in the second act, makes him a rich man. Everybody dances. There are inconsistencies and superfluous details in the mise en scène which Petipa doesn’t seem to have given a fig about. Why does the good fairy appear after Harlequin has already been revived? To what end does a clump of drunken soldiers march through the square, like the company of soldiers in Donizetti’s Elixr of Love? What is this opulent ballroom in which the second act takes place, so incongruous in relation to the modest cityscape of the first act? Such narrative carelessness can certainly lead one to scratch one’s head; it also interrupts the flow. Perhaps Ratmansky should have intervened more, smoothing out transitions, cutting a few passages, reordering others.

© Robert Perdziola. (Click image for larger version)

But really, what lights up the ballet are the dances, particularly in the second act. The crowning glory is the “Chasse Aux Alouettes” (hunt of the larks), an allegorical ballet-within-the-ballet in which Harlequin plays a hunter and Columbine his prey, surrounded by a flock of larks, dressed in gorgeous gray-and-lilac tutus decorated with feathers. Embedded within this dance is a delicious pas de deux. Columbine swoons, her arms dangling down like vines. Later, she rests artfully against her partner’s side, fitting her body perfectly along the line of his back. She bourrées away from him, through lines of dancers, always just out of reach. (Echoes of the “Vision Scene” in Sleeping Beauty.) Her quiet, legato solo, to a harp melody, has her slowly unfolding one leg while tilting her torso away and fluttering her fingers. She hops, executing a half turn, then bourrées forward, floatingly opening her arms before her. These moments feel almost miraculous in their delicacy and musicality. Particularly as danced by Isabella Boylston at the première on June 4.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

Already enjoying a strong season, Boylston seemed to blossom yet more in this ballet. It suits her perfectly: the charm, ease, sparkle and musicality of her dancing are elemental aspects of Petipa’s style, at least as relayed by Ratmansky. The technical challenges, too, fall well within her toolbox of skills: hops, turns with the leg moving from the side to the back, balances, beaten jumps, piquant pas de chats.

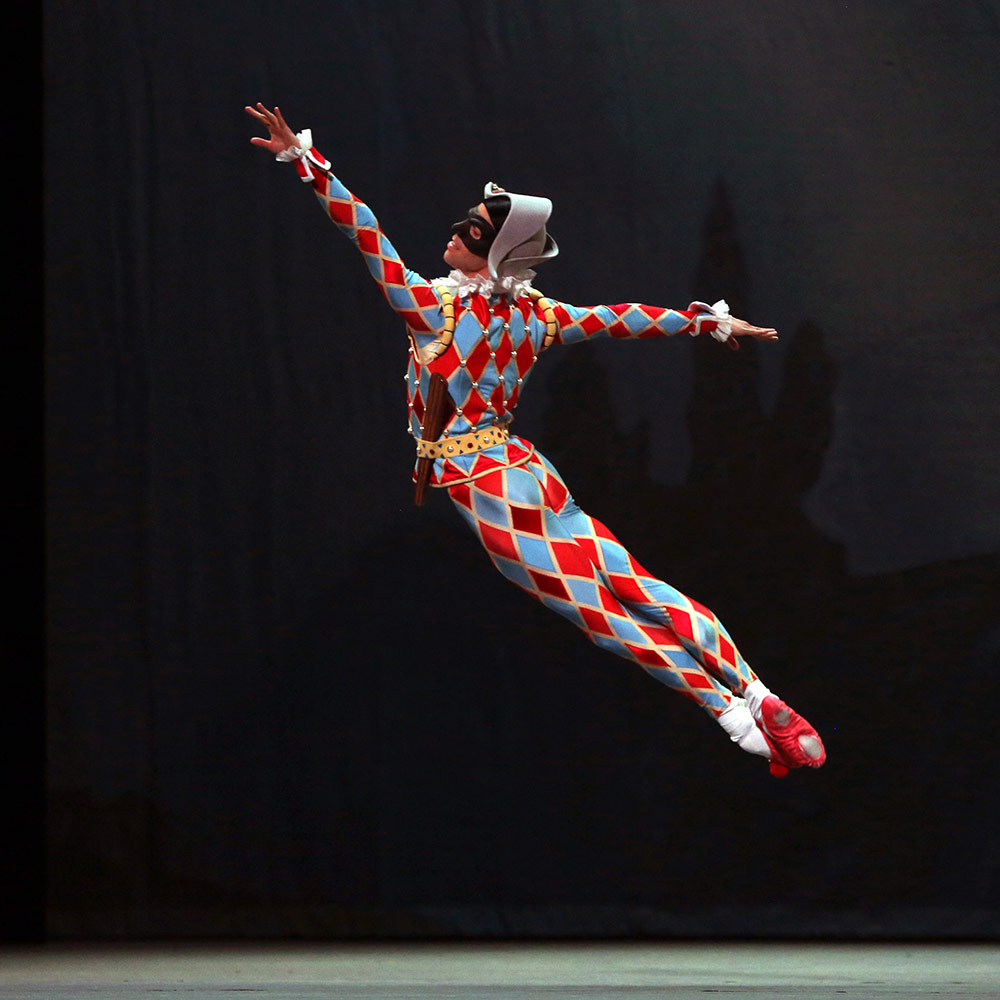

James Whiteside, her Harlequin, was equally well-suited to his role. A naturally sprightly dancer, he seemed perpetually to be skittering on hot coals, knees lifted, feet prancing. The many complicated beaten jumps gave him no trouble at all. He gave a breezy, happy performance, despite being saddled with a half-mask and hat (with pom-poms on each side!) the whole time. Have I mentioned the costumes, executed by Robert Perdziola and based on the originals, by Ivan Vsevolozhsky? Well, it’s time I did. They are opulent, colorful, heavy. Everyone wears a wig or a hat, sometimes both. (Ratmansky is obsessed with hats, it seems.) Almost all of them are lovely – particularly the two costumes for Columbine – though there are some jarring color juxtapositions in the second act. Their opulence, too, is part of the show – this ballet isn’t only about seeing the dancers’ bodies move, but also about how the fabric moves as they dance.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

The cast of leads was completed by Gillian Murphy, witty and piquant as Pierrette, and Thomas Forster, who embodied the droopy, long-sleeved Pierrot with affecting fecklessness. The supporting cast included a resplendently smiling Tatiana Ratmansky (wife of the choreographer) as the Good Fairy; Roman Zhurbin, uncharacteristically lost in the role of Columbine’s father; and a hilarious Duncan Lyle as Léandre, the older suitor. Three other casts will take on the ballet over the course of the week.

Isabella Boylston and James Whiteside after a truly charming performance in Alexei Ratmansky’s reconstruction of Petipa’s Harlequinade for ABT. pic.twitter.com/4PnPdNL29n

— Marina harss (@MarinaHarss) June 5, 2018

As I sat in the darkened Met watching the second act divertissement, I felt a strange excitement: was this what people felt when they watched ballet in St. Petersburg in 1900? Well it is and it isn’t. We all know that. But what is sure is that a different kind of ballet, softer and more delicate, emerges from these steps. The story may be slim, but the pleasure of discovery is deep.

* As part of my research for a book on Ratmansky, I have been following his rehearsal process.

What a tempting review! Can’t wait to see it on Friday night!