© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

Staatsballett Berlin

La Bayadère

★★★★✰

Berlin, Staatsoper Unter Den Linden

4 November 2018

www.staatsballett-berlin.de

Himalayan Reverie

In the last several years, the choreographer Alexei Ratmansky has developed a sideline to his main choreographic efforts: the reviving of ballets by Marius Petipa in a way that represents the original choreography with as much fidelity as possible over a century after it was created. This is possible because of the existence of a trove of notes written in Stepanov Notation (invented by Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov, a dancer at the Imperial Theatres in Russia), recorded in the early 20th century, when Petipa was still alive, but close to retirement. Petipa himself disliked the practice of notating ballets, referring to the resulting documents as “skeletons” and scoffing that they had “no place in the choreographic art.” Like Balanchine after him, he had the habit of re-choreographing passages from his ballets for each new group of dancers that came his way.

Petipa, though, is long gone, and one can only wonder what he would have thought of the versions of his ballets that have been generated over the ensuing decades. Countless interpolations, cuts, and alterations have been made. Ratmansky (*) said recently, at a conference before the opening of his new “reconstruction” of Petipa’s La Bayadère for Staatsballett Berlin, that what drove him to delve into these revivals was a desire to get closer to the original ballets. (In opera, this is done through “critical editions” that attempt to recover the score in its original form.) As he put it, the versions of Petipa he had seen and danced no longer satisfied his eye; they all seemed to be missing something, and he wanted to understand what that something was. “There were so many questions,” he said, “I felt I had to find out for myself.”

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

So in 2013, as a side project, he and his wife Tatiana learned how to decipher the notations, most of which are now kept at Harvard’s Houghton Library, with the help of a couple of early twentieth-century manuals, and began to use them to create what one could loosely call “reconstructions” for various companies around the world. First came Paquita, for Munich; then The Sleeping Beauty for American Ballet Theatre and La Scala; Swan Lake for Zurich and La Scala; Harlequinade for Ballet Theater; and now La Bayadère for Staatsballett Berlin. For the past half-decade, this “sideline” has become almost as central to his choreographic work as the creation of his own original ballets. It has also affected his own approach to choreography, best reflected by his recent ballet Whipped Cream, which in many ways is constructed along the lines of a Petipa ballet.

“Reconstruction” is a funny word; one can’t really recreate a performance from the past. Notations are incomplete; they record a particular moment in time in the trajectory of works that were constantly evolving; bodies, ballet technique, and pointe shoes have changed. The audience has also changed – you can’t (and shouldn’t) forget all the ballets you’ve already seen, the speed of Balanchine, the complexity of Ashton, the heroism of MacMillan. Like an tenor who sings high c’s with a strong, ringing chest voice (do di petto) a dancer is expected to dance with the acrobaticism of an Olympian.

Ratmansky’s approach, therefore, is both personal and idiosyncratic. With the exception of Harlequinade, Ratmansky hasn’t been a stickler about using original designs. The contradiction between fidelity to the steps and freedom in the visual context doesn’t seem to bother him. As he said in Berlin, “I believe that ballet, the heart of it, is the choreography, the steps.” But despite his rigor and fidelity to historical sources – he also consults period photographs, early films, notated musical scores, notes in Petipa’s own hand – Ratmansky doesn’t claim archival authenticity. “This isn’t a history book,” he once told me, “it’s a live performance.”

So, back to La Bayadère. Petipa staged it twice at the Imperial Theatres, first in 1877 and then in 1900. The notes date from the latter staging. (Ratmansky believes they are in Alexander Gorsky’s hand.) The notations, he has said, were very complete – including movements for the heads, torso, arms and feet – but had important gaps, including the solos for the main characters of Nikiya, Solor, and Gamzatti. Ratmansky had to put these together from traditional versions, or, as in the case of Solor’s main solo in act IV, ended up making up his own choreography “in the style of” Petipa. For Gamzatti’s solo at the end of the ballet, he interpolated music and choreography from another Petipa ballet (La Vestale) with music by Riccardo Drigo, but included in the 1900 version of La Bayadère.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

In addition to the Stepanov notations, Ratmansky and Tatiana (who, as always, assisted in the reconstruction) had at their disposal a score from the Bolshoi written sometime in the 1870’s, some notes in Petipa’s hand, an 1877 scenario, photos, and documents from the time. They consulted various other versions, including the 1941 Vakhtang Chabukiani staging for the Kirov, Sergei Vikharev’s 2000 reconstruction, and even an amazing stop-action film created between 1906 -1909 by the Russian dancer and film pioneer Alexander Shiryaev. The new designs, loosely inspired by the originals, are by the French designer Jerôme Kaplan.

La Bayadère is an exotic ballet, set in a fantastical version of “Ancient India.” Such ballets have fallen out of fashion because of contemporary sensibilities surrounding orientalism, exoticism, and the inaccurate portrayals of distant cultures. Like the operas Aida and Madama Butterfly, La Bayadère certainly includes all of these elements; it was made at a time when Europe was fascinated by the exotic East, and when several European countries had colonies. The European eye was hardly subtle in its interpretation of foreign lands.

What Petipa and others (like the painter Delacroix) had was curiosity and a Romantic fascination with, at the very least, the trappings of foreign civilizations. In 1838, a group of Indian dancers toured Europe, creating a sensation; even earlier, Auber had created an opera for the Paris Opéra, Le Dieu et la Bayadère, with a ballet divertissement by Filippo Taglioni. In 1869, the Suez Canal was inaugurated; in 1871, Verdi’s Aida, set in ancient Egypt, had its première. And in 1876, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) visited India and Sri Lanka, a voyage breathlessly covered by all the European journals and newspapers of the time. While visiting Sri Lanka, he even witnessed a masked, or “devil” dance, a scene captured by the painter Godefroy Durand. That scene is likely the inspiration for the spectacular, rousing “Danse Infernale” that takes place in the big divertissement in act II of Petipa’s ballet.

It goes without saying that Petipa’s India is deeply inauthentic, as is its accompanying score, by Ludwig Minkus, who made only the most superficial efforts to include vaguely non-Western-sounding motifs. Much of the music consists of waltzes, polkas, and triumphal marches – all rhythmic and great for dancing – but there is the odd exotic melody for flute or clarinet. Ratmansky dispensed with the familiar John Lanchbery orchestration, and had a new, lighter, more rhythmically lively one created for him by two British musicologists, Lars Payne and Gavin Sutherland. Under the baton of Victorien Vannosten, tempi have been kept brisk, dancey. The entrance of the Shades, in particular, was noticeably more dynamic, with a corresponding effect on the quality of the movement: more crisp, pulsating, and unreal, less aqueous and romantic. The soloists of the orchestra, particularly on the harp, violin, cello, and flute, created a vibrant, singing accompaniment whenever the score allowed.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

The exotic locale supplies the palette of designs: temples, elephants, tropical plants, veils, loose harem pants, decorative turbans, approximations of saris. And of course, the spectacular vista of the Himalayas that is the setting of the ballet’s most famous scene, the “Kingdom of the Shades.” Thanks to Kaplan’s designs, Ratmansky’s Bayadère doesn’t stint on color or richness of design. The effect is of a storybook India, interpreted through a contemporary European eye informed by Art Nouveau. The stage is often framed by patterned panels, like an architectural detail by William Morris.

The evening is divided into two halves, with one intermission. The first, mostly devoted to storytelling through mime and physical interactions, ends in the grand procession celebrating the betrothal of Solor (a warrior) and Gamzatti (the Rajah’s daughter), a divertissement, and the death of Nikiya (Solor’s secret love, a temple dancer). The second begins with Solor’s desperate visions of the dead Nikiya, followed by the famous Shades scene, and ending with the ill-fated wedding of Solor and Gamzatti, decisively cut short by an earthquake. (The gods have been offended!) Most of the dancing, with the exception of a suite of dances during the grand betrothal scene, is in the second act.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

This makes for a completely different experience of the ballet, particularly if the production one is used to is Natalia Makarova’s for American Ballet Theatre. What happens, in essence, is that the evening builds and builds, from mime and storytelling to pure, abstract dance in the Shades, with the bravura dancing saved for the final act. The expressiveness of the mime is essential, and it is clear that the Ratmanskys placed great emphasis on bringing out the dancers’ actorly qualities. They also invited a specialist in Indian dance, Rajika Puri, to help them connect the movements – a touch to the head in greeting, the placement of the arms on the chest – with their underlying meanings, fanciful as they may be.

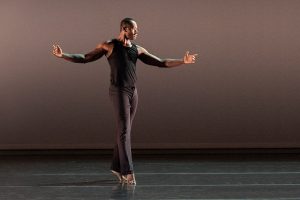

Polina Semionova, who danced the role of Nikiya at the opening, was particularly touching, direct, fluid, and un-mannered in her movements; she also uses her eyes with depth and soufulness . She reads to the rafters. Solor, Alejandro Vireilles, had a more conventional presence, but then he has the least to do in this more old-fashioned version of the ballet. (He doesn’t dance a solo until the last act.) Yolanda Correa, Gamzatti, was direct and clear, both in her mime and in her dancing. But the most vivid presences onstage, besides Semionova, were the character dancers: Vladislav Marinov as the lead Fakir, who orchestrated Solor and Nikiya’s trysts; Vahé Martirosyan, an authoritative Brahmin; and Tommaso Renda as the haughty, demanding, but essentially decent Rajah.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

The most moving passage of mime was a heart-rending scene in which Nikiya played the sitar in a window of the temple, dreaming of Solor as he listened from below. The music is for flute and harp; Semionova plucked and moved her hand across the strings as if really playing. When Solor called out to her, she ran down to meet him. The two shared a moment of real intimacy, with Semionova melting into Virelles’ arms.

The sitar returned in the famous Nikiya adagio – also not notated. It made sense; the temple dancer was, after all, there to entertain the court. The familiar longing-filled lunges and backbends seemed to respond to the melody rising from her instrument. But my favorite passage in this act was the opening triumphal procession, led by a troupe of boys from the Staatsballett school, rocking back and forth in a kind of exaggerated marching dance. They were followed by various groups, many of them advancing with a little sideways tapping step that played with a rhythmic theme in the music. The entire march danced, leading naturally into the large ensembles of weaving lines Petipa is so famous for.

But perhaps the real triumph of the show is the Shades act. The combination of the set, which really suggested a descent from the skys down the slopes of the Himalayas, the golden lighting, the long tutus and diaphanous veils, and the lilting choreography, was extremely effective. The Shades step was similar, though not identical, to what one is used to seeing: an arabesque reaching forward (but without a bend in the leg), then fifth position, then an extension of the leg forward while the body arched back, and a quick little sweep of the foot from front to back, executed over and over. The 32 dancers completely filled the stage, creating an effect like a human cloud, ghostly, otherworldly.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

The pas de deux that followed, for Solor and Nikiya, followed the familiar pattern, but, again, with a different feel – less heroic, more intimate. Particularly striking were the moments in which Semionova walked hand in hand with her lover, or whispered quietly into his ear. In the final image, she leaned her body softly toward him with her hand on her heart as he knelt by her side, supporting her from below, a pose echoed at the end of the ballet.

The more virtuosic dancing came at the end (rather than in the betrothal scene, more typical). Correa and Virelles did not disappoint, even if, in this production, the solos are somewhat less showy than in more modern stagings. Italian fouettées, hops with rond de jambe (for Gamzatti) and every manner of jump (assemblé, cabriole, sissonne developpé, etc, for Solor) were executed cleanly, confidently. More interesting was how Nikiya repeatedly interrupted the scene, often pulling Gamzatti away or twirling her in her arms. A second man, Alexei Orlenco, arrived to partner Semionova in some ghostly lifts.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

My only real criticism – though I understand that some might find the amount of mime hard going – is with the very end of the production. For the earthquake, Ratmansky and Kaplan decided to use a projection, an unconvincing and anti-climactic choice. The ending of the ballet is rather abrupt, almost as if they had run out of music. After Nikiya raised Solor from the dead, the two posed together for just a moment as the curtain was lowered. The impact of the moment, long in coming, was lost.

The pleasures of this Bayadère lie in its subtlety and, even more, in its abundance of detail. One senses that much thought has been given to every moment in the ballet; each step and gesture has been shaped, considered, filled out. The resulting ballet has style, and that style feels harmonious and assured. It’s not a star vehicle; people who came to see Semionova knock them out of their seats may have gone home disappointed. Some of the technical aspects, like the hops on pointe, the quick transitions between steps, and the shoulder-height lifts, seemed to challenge the dancers, and that, in itself, was interesting to see. As was the great variety of dynamics throughout, from small, delicate footwork to wild and percussive (in the danse infernale) gallops, to Romantic and fluid partnering.

Whether it will please the audience, accustomed to the more steely, heroic dance technique of today, is a question that will be answered over time. As Ratmansky said at the pre-performance talk, “these reconstructions require a certain open-mindedness.”

* This was not so coincidental; the trip was part of my research for a project devoted to the choreography of Alexei Ratmansky.

Marina, as usual — Brava, brava — I can hardly wait for your bioigraphy of Ratmansky,

Many thanks, Renee!