© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Apollo, Orpheus, Agon

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

22 January 2018

www.nycballet.com

davidhkochtheater.com

Gods in Training

There has been a generational shift at New York City Ballet, that much was clear last night in a program of Stravinsky ballets that included two major débuts and several smaller ones. The focus was on Balanchine’s “Greek” ballets: Apollo, Orpheus, and Agon, creatd in 1928, 1948, and 1957 respectively. The surprise of the evening was perhaps Orpheus, long declared dead by Balanchine aficionados, and seldom performed. Though flawed, it rang out with unique poetry; several images, including the final passage, in which a dancer carries a mask of Orpheus around the stage, coaxing it into a haunting song (played on the brass in the pit) lingered long after the curtain had come down.

Much of the audience’s attention was, understandably, focused on the début of a new Apollo, Taylor Stanley. He is only the second non-white dancer to perform the role at the company (and the previous one, Craig Hall, did so only once). But this fact, though historic and important, was not the most remarkable aspect of his début. What was more interesting, at least to this viewer, was a shift in how this balletic character is portrayed, customized to the gifts of this particular, and very special dancer.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Ever since Peter Martins’ depiction of Apollo as a resplendent Nordic god in the sixties, this esthetized interpretation has become the norm. Chase Finlay – recently fired from the company for his extracurricular activities – was the latest version: tall, statuesque, noble, and authoritative despite a certain youthfulness. (And don’t get me wrong, his was a beautiful Apollo.) Taylor Stanley’s interpretation is about as far from this as one can imagine. His far more personal approach subtly transformed the ballet into a series of explorations and tests, a real esthetic training-ground for a young god. He took risks, allowing the character at times to fail, and stumble, and lose his breath. Stanley was playful, curious, reverent, and, in the end, suddenly aware of his place in the universe of the gods.

The performance was all about the details, which “spoke” more than in any other interpretation I have seen, other than that of Nikolaj Hübbe. When he called out to the Muses with his hand, one could almost hear his voice; when he “heard” the call of Zeus, he lifted his head from the Muse’s hands with an air of slight surprise. In the first sequence of steps, he really seemed to be testing the range of his abilities, bravely tipping off-balance and then catching himself mid-fall. There was a touch of theatricality in his interpretation, atypical at this reticent company – perhaps this was what reminded me of Hübbe, a fantastic actor–and this approach added nuance to the ballet’s underlying story. It was less noble, more alive.

Stylistically, Stanley, who is on the slight side, chose a path that suited his build and personal approach to movement: sometimes angular, sometimes soft, not particularly turned out, shape-shifting, strongly accented. Where appropriate, he gave in completely to the movement, creating the impression of great freedom, even liberation. Overall, the focus was on interpretation, rather than on a generic idea of what an Apollo should look like. He had only one slight moment of hesitation, when the young God wraps one leg around the other and lowers himself to the floor. Stanley managed the move without incident, but like many before him, he looked cautious and a little tense. (It may be the most awkward moment in the ballet.)

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Stanley’s Muses were Tiler Peck (Terpsichore), Brittany Pollack (Polyhymnia, another début), and Indiana Woodward (Calliope). All were excellent; Woodward’s sharpness of attack, the way she crouched in pain at the exact moment the orchestra (under the baton of Andrew Litton) hit a low chord, made a particularly strong impression. Peck’s Terpsichore was playful and bold; like Stanley, she took risks and played with the musicality. It was particularly noticeable when, after sitting on Apollo’s knee, she pulled him up from the ground; the gesture revealed the relationship of teacher to student beautifully. Their pas de deux didn’t achieve the rapture of other, more experienced, pairings, but there is time. The four dancers were of similar height, an interesting change from the usual dynamic; it gave the final image of the starburst – three arabesques at different heights – a more equal, harmonious look. City Ballet does the revised, cut version of Apollo, without the climb up to Mount Olympus; I miss the birth scene included in the longer version, but I find this simpler ending very beautiful.

If there was less buzz about Orpheus it is because the ballet itself has, to a certain extent, been written off by historians and critics. The general consensus is that there is not enough dancing, and what there is is too symbolic, too heavy with meaning,; ditto for Isamu Noguchi’s bulbous sets and primitivist costumes. I agree about the sets; the giant rocks and strange aquatic protuberances bulging from the wings are slightly funny, but not about the costumes, which strike me as mysterious and non-realistic in an interesting way. The most striking element in the ballet is Orpheus’s relationship to his oversized lyre, which he carries, plays, caresses, even prays to. It is also, notably, the symbol of New York City Ballet, and because of that, carries a particular symbolic weight, like a talisman.

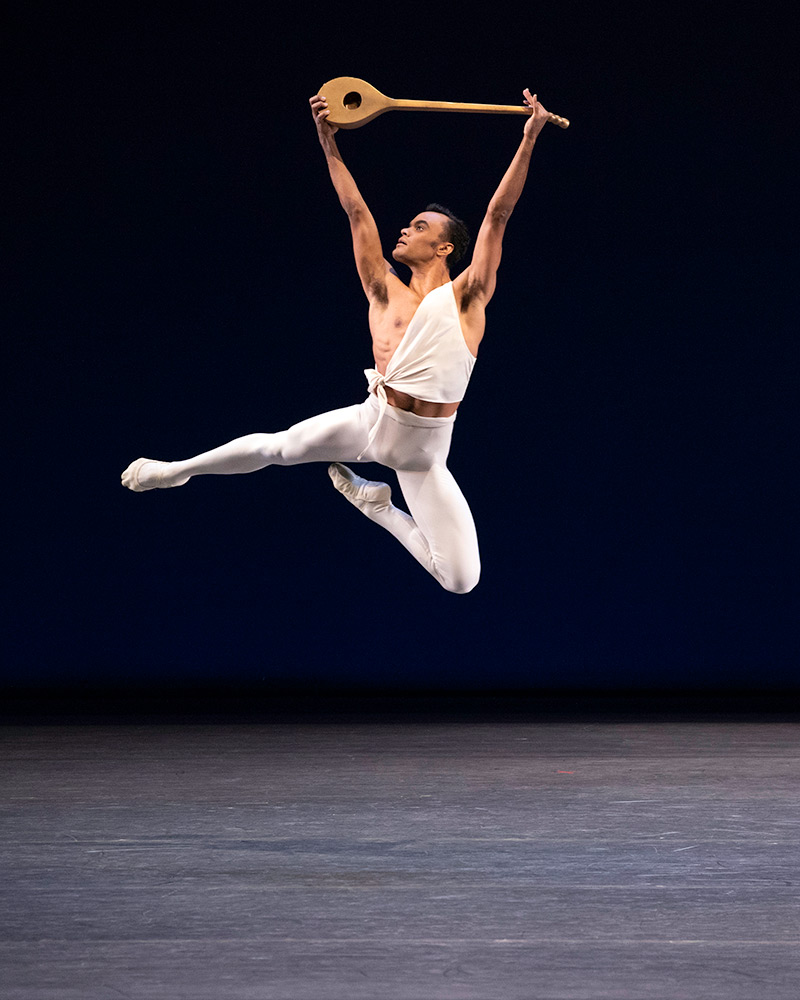

What is the factor that can bring a ballet long considered dead back to life? A dancer. And in Gonzalo García, the company may have found just the man for the job. García specializes in characters whose movement is softened by doubt, or sadness, or reverie: Jerome Robbins’ “Opus 19: The Dreamer,” “Melancholic,” the man in brown in “Dances at a Gathering.” His body seems to stretch out and melt with longing; his gaze goes inward. All qualities that suit Balanchine’s “Orpheus,” who, at the start of the ballet, has already lost his beloved Eurydice.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

He stands at her tomb in a dejected, almost deflated pose, his lyre abandoned at his feet. Then, he picks up the lyre and plays despondently, at one point lying on the floor and plucking at the strings with one hand (the lyre is represented in the pit by the harp). He repeats the same phrase of movement several times, almost ritualistically. A dark figure (Peter Walker, another début) appears, wrapped in a rope, which he then attaches to Orpheus’s hands. Who is he? In the program, he is identified as the “Dark Angel;” one senses he represents Orpheus’s destiny. Slowly, as if moving through water, he pulls Orpheus toward the underworld; the two men’s hands are connected through the lyre, which hangs between them.

All of this struck me as much more moving than I remembered from the last performance I saw several years ago. The sadness, the mysterious relationship between the two men, the role of the lyre – all were imbued with great poetry. But in the Underworld, the ballet loses its way. The dances for the Bacchantes are flimsy and downright silly, as are, later, those for the Furies. They are like an unconvincing version of Robbins’ The Cage, all hair and outstretched limbs and prancing on pointe. How could Balanchine’s imagination fail him so completely?

Things improve as Orpheus recovers Eurydice and leads her, painfully, toward the world of the living. The language here is driven by longing; the partnering is acrobatic, twisted, full of moves in which Eurydice wraps herself around her lover’s body. (There is a hint of the Siren, from Prodigal Son.) But here, the interpretation of Sterling Hyltin (another début), though delicately danced, didn’t quite work. She was kittenish rather than loving; her desire to be seen felt too slight, too coquettish. Which made the inevitable denouement far less dramatic.

And yet! The ballet found its footing again at the end, with the appearance of Apollo, carrying a giant mask, singing that final, haunting serenade. If only the two ensemble sections were better, Orpheus could be a great ballet.

It is a pleasure to see a new generation of dancers step into these roles. They have clearly thought deeply about them and molded them to their bodies and minds. It just goes to show, it may be too early to declare this or that ballet to be beyond saving. Sometimes, all it takes is a new dancer, a clean slate, fresh eyes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.