© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Apollo, Orpheus, Agon

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

26 January 2019

www.nycballet.com

davidhkochtheater.com

Stravinsky Redux

Nothing revives a repertory like new casting. It’s like having the dust swept off a beautiful painting – the colors look fresh and sharp. So we can be grateful to the interim leadership at New York City Ballet for reconsidering who gets to dance some of the company’s most elemental repertory: Agon, Apollo, Serenade.

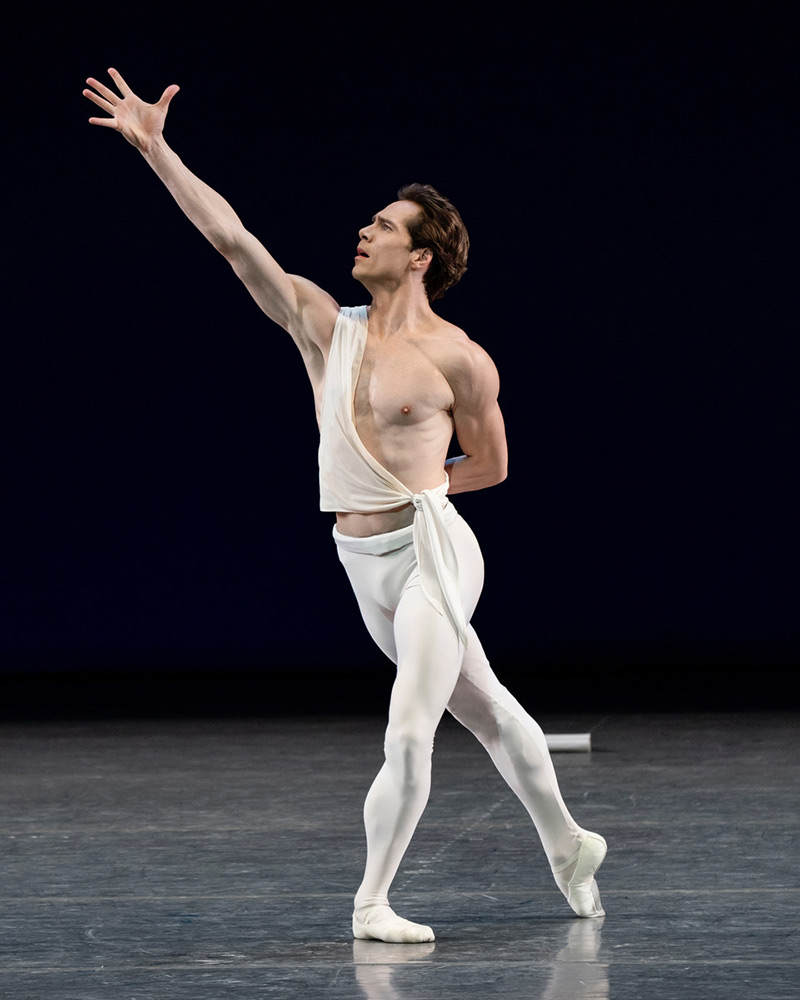

On the evening of Saturday the 26th, New York got its newest Apollo, Gonzalo García. Even though García has been with the company since 2007, and had already performed the role for his previous employer, San Francisco, he had never done so here. Who knows why? This week, like Taylor Stanley, he finally got his chance.

One of the most heartening aspects of these débuts is realizing how varied the interpretations of this role can be. If Stanley was introspective and highly detailed, García was passionate and lyrical. There was a greater sense of propulsion in García’s approach, and a warmer connection with his Terpsichore, Sterling Hyltin. His footwork was less crisp, yes, but his performance had other qualities: freedom in the partnering and a beautiful port de bras and upper body, lyrical and soft. Both débuts were remarkable and I look forward to seeing these dancers grow into the role. (In another début, Abi Stafford danced an impeccable Polyhymnia.)

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Both casts were enhanced by a muscular, dynamic rendering of the score by the orchestra, under the baton of Andrew Litton. How it helps to really hear the rhythms, and to have the strong support of Stravinsky’s harmonies to buoy the steps. (Many conductors over-emphasize the “white,” diaphanous aspect of the score.) The section in which Apollo and the muses form a troika and gallop across the stage was particularly excitingly played. Stanley gave the impression of whipping the horses into a frenzy; García seemed to be at pains not to fall off his chariot.

On another side note: though I also love the longer, original version of this ballet with the birth scene of Apollo and the ascent to Mount Olympus at the end, I have to say, I find the shortened version just as compelling: I’m always struck by the beauty of the opening image, with Apollo holding his lyre as the curtain rises, one arm stretched above his head; and by the final tableau, in which the four dancers gravely walk in a line and then, without warning or transition, form the final figure, with Apollo lunging forward and the three muses leaning behind him in arabesques of different heights, forming a sunburst of legs. The image resonates all the more because it has been prefigured in different versions throughout the ballet. It takes your breath away.

Orpheus, last performed here in 2012, is making a comeback this season; setting it in the middle of this Grecian triple-bill is a good idea, as it connects it to some of the themes in Apollo and Agon, above all the importance of music as a central theme in Balanchine’s imagination. The performance on Tuesday, led by García, was more compelling than the one on Saturday, in which the title role was played by Ask laCour, whose understated rendition felt sketched, rather than fully realized. If there is a ballet that needs a fully-imagined performance at its heart, it’s this one. However, his partners, Teresa Reichlen as Eurydice and Andrew Scordato as the Dark Angel, were excellent. (Both were débuts.) Scordato’s long, stretched out lines amplified the role’s dark power. Reichlen avoided the kittenish aspect of the role, using her lithe, pliable body to wrap herself around Orpheus in a way that made it clear he was doomed from the start. Her acrobatic moves communicated a sense of urgency, the need to be seen – who among us has not felt this? How could Orpheus, or anyone, resist?

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Agon, too, got a refresh, with débuts from Sara Adams (well matched with Lydia Wellington in the courtly “gaillard”), Emilie Gerrity (lean and collected in the second pas de trois), and Russell Janzen, paired with the tall, lyrical Miriam Miller in the combative pas de deux that is the climax of the ballet. Like The Four Temperaments, this is a ballet that is constantly in rotation at City Ballet, and run-of-the-mill performances are not infrequent. It is easy to lose the edge of competition and combat that is implicit in the title. So it’s especially good to see a cast that manages to rekindle that electricity. Peter Walker (not a début) brought his gangly, edgy quality to a male solo that begins with an advance from the back of the stage to the front, jumping and shooting his legs forward like arrows. Combined with the xylophone in the orchestration, his dancing gave him the look of a slightly malevolent jester.

Emilie Gerrity, a powerhouse-in-the making, kept her cool in her trio with Harrison Coll and Andrew Scordato – holding her balances nonchalantly – but the section felt a little frazzled, with the two men scurrying around to make sure everything went as it should. In the dance with the castanets (the “bransle gay”), Gerrity might have found more space to luxuriate in the movement. How much more effective this scene is when, as in this case, the two men onstage do not clap their hands to the beat, but rather allow the castanet’s dry sound to rise from the orchestra pit.

Russell Janzen and Miriam Miller make an interesting pair; she is so delicate and lyrical, and he so noble and attentive in his partnering. He is an atypical Agon lead, with a more “romantic” quality, less edgy and remote than the norm. The care with which Janzen takes Miller’s foot and pushes it behind her into a high extension gives this passage the feeling of a lesson, an impression strengthened by the fact that she then takes her own foot and repeats the action on her own. “I don’t need you,” she is proclaiming, raising her foot even higher. The gentleness of the beginning gives way to greater and greater friction. When Stravinsky’s music shifts to repeated chords on the strings, the woman seems to be gathering her forces for an attack; after that, when the man takes her hand, she fights, leaping in every direction, like the Firebird. By the end, the two fall into an exhausted, erotically charged heap.

Which is as it should be. May the season bring more performances like these.

Such a fine column – it’s a keeper!