© John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation – used with permission. (Click image for larger version)

This conversation was originally held as part of the “In Pursuit of Petipa” symposium at Houghton Library, Harvard University, on Nov. 9 2018.

The Houghton Library is also the home of the Nikolai Sergeyev Collection, which contains over two dozen scores of ballets and opera ballets by Marius Petipa, recorded in Stepanov Notation. The Q&A has been slightly edited.

MH: You and your wife Tatiana staged a historically-informed La Bayadère in Berlin in November of 2018. At a talk before the premiere, you said that the development of classical dance in Russia in the 20th century had been unnatural. What did you mean by that?

AR: I was mostly talking about Soviet Russia. As we know, two thirds of the Imperial Theatre left after the Revolution, and those who stayed were facing a new reality. There is a wonderful painting called “The New Audience”; it’s the royal box filled with very simple people, eating apples, putting their feet up, smoking. These were the audiences that the theatres faced. So they had to reconsider the repertory. Aristocratic elegance was no longer relevant in the 30’s and 40’s. So, Agrippina Vaganova and Fyodor Lopukhov and others started working hard to face this new reality.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

From Marina Harss’ interview: “Alexei Ratmansky – Simple and Wise, a Q&A about Ratmansky’s Sleeping Beauty for ABT“

If you compare the pictures of the dancers pre-1917 and post there is a huge difference in posture, in lines and shapes, let alone the costumes which became cheaper and simpler and less esthetically pleasing. All of that affected ballet. Of course, no-one questions Vaganova’s genius; we can’t judge them for what they did with Petipa. Petipa had to change. A lot of emigrés in America and in Europe tried to preserve the style.

MH: You danced in Denmark for several years. In your opinion, has Bournonville been better preserved than Petipa?

AR: Yes, in a sense. On the other hand, the thing about the Petipa’s ballets is that they traveled around the world and are the base of the repertory of any company. Yes, Petipa was changed and this may be the reason it became so popular. This is a big question, and you can answer it in different ways.

MH: You have done several stagings of Petipa ballets that draw upon the information found in the Stepanov Notations here at Harvard. What do these notations contain?

AR: Vladimir Stepanov was this extraordinary young man who wanted to invent a new system of notation. His book, The Alphabet of Movements of the Human Body, was published in France, and then the administration at the Russian Imperial Theatres approved notating the repertory and the method was taught in school. Each graduate knew how to read the notations. So, until late 1910’s the whole repertory was notated. The fact that the collection was taken out of Russia by Nikolai Sergeyev and ended up here is pure luck. I’m afraid to think what would have happened to them if they had stayed in Russia. So, it’s amazing that they exist and we can work with them.

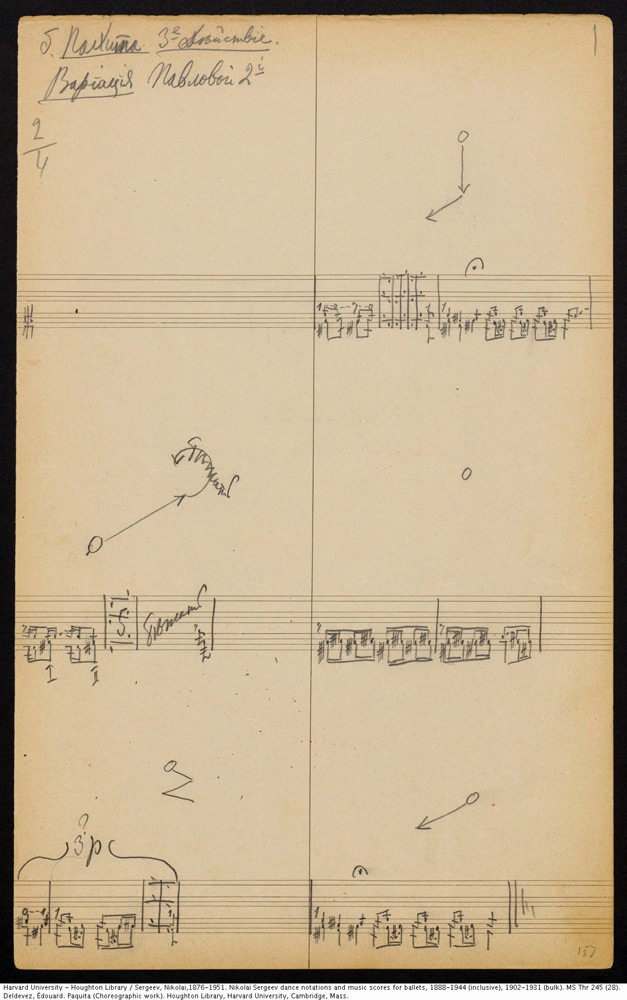

A page of Stepanov notation for the Paquita Grand Pas. © Image courtesy Doug Fullington.

From Marina Harss’ interview “Doug Fullington – on Stepanov Notation“

The notations are like musical scores. They preserve the mechanics of classical dance. No French terminology is used. Instead, each movement of the arms, torso, head, arms, every joint, even the hands – but no fingers – are indicated. If it’s notated fully it gives you the exact mechanics of the dance, which is a miracle. When we reconstruct the movements based on the notes, we can see how the movements were done during Petipa’s lifetime.

MH: Is it possible to read the notations in different ways?

AR: In theory, no. And the Bayadère notations are absolutely extraordinary. Having seen the manuscripts of Alexander Gorsky at the Bolshoi Museum, Tatiana and I recognize the handwriting. I don’t have proof, but I’m convinced Gorsky did them before he moved to Moscow.

© Fabrizio Ferri. (Click image for larger version)

From Marina Harss’ interview: “Alexei Ratmansky – Balletic Musings, a Continuing Conversation”

There are thirteen main dances in Bayadère, annotated in great detail. This includes the height of the leg, the degree of the bend, the direction of the tilt of the shoulders, the floor plans, the direction the dancer is traveling in. And also the musicality.

The notation is divided by musical measures and the notes indicate the duration of the movements. There are half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc.

MH: So, in principle you could put the musical score next to the Stepanov notation and it should correspond?

AR: Right. For example, in the score for Bayadere all the dances for he corps de ballet and second soloists are notated beautifully. However the notations for the dances of the principals – Nikiya, Solor, and Gamzatti – are very few. We don’t have the dance with the basket and the snake, and we don’t have Nikiya’s first dance, or Nikiya and Solor’s adagio in the “Shades” act, or the variations for Gamzatti and Solor. These are huge gaps which we have to decide what to do with. Of course there are traditional variations we could use. We used a combined approach.

© Yan Revazov. (Click image for larger version)

From Marina Harss review of Staatsballett Berlin in Ratmansky’s reconstruction of La Bayadère – premiered in Berlin in 2018.

MH: The dancer Alexander Shiryaev, who also worked as Petipa’s assistant, made these extraordinary stop-action films of various Petipa dances. Did you use any of those?

AR: There is a stop-action film made with puppets, of the “Danse Infernale” in Bayadère. The whole dance is shown. It was a great help because in the notation of the drum dance, the movement of the arms goes up and the front leg is attitude, whereas in today’s versions in Russia the movement is down, and the leg is stretched in front. You can see the earlier version in the Shiryaev film.

Alexander Shiryaev. First puppet cartoons. 1910-1920 years. From Vladimir on Vimeo.

MH: Are the notes always clear?

AR: There is one step – pas de chat and saut de chat – that is executed either with bent knees or with a stretched front leg. But in the notations the front leg is always indicated as being stretched, so the question is, did they always do it that way or is that just the way it’s notated? So when we worked with Doug Fullington he explained to me that this is just the way it’s written down, and that sometimes it was, in fact, executed with bent knees.

MH: Was it like a shorthand?

AR: That’s right. The bigger question is: should we believe every single bend of the knee in the notes or should we use the notation as a point of departure and translate it to a more familiar coordination? For me the answer is clear. I want to really stay close to what’s written because for my taste it is better, except in a few small cases, like this pas de chat.

There was a very interesting moment with Doug Fullington during one of the first rehearsals of our Paquita at the Bayerisches Staatsballett. We were staging the pas de sept bohémiens. It was an incredible feeling to see it emerge before our eyes. We were doing this sequence – step, fouetté, arabesque – and Doug said, “there’s a little hop step written there. I’m sure it doesn’t matter because it doesn’t make any sense.” And then we tried it and the result was this staccato rhythm with a little hiccup in the middle. We had a long discussion and he said look, there are 2 ways to do it, one is exactly what is written down and the other is without this little hiccup. And both of us agreed that the way it is notated is more interesting rhythmically. That was a turning point. From then on, we decided to try to stay as close as possible to the notes, and the result was very inspiring, very encouraging.

© Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

My experience with Tatiana is that when something seems like a mistake, that means we need to come back to it and find the key. What is in the notes is always better, to my taste, than what we would have come up with by just translating it into today’s coordination.

MH: What have the notations taught you about Petipa’s compositional style in general?

AR: I would say the first thing that is obvious is that this man spent a great deal of time preparing. The choreography has a steely logic. You can’t remove a step without destroying the whole structure. It’s so amazingly balanced. It’s what defines classicism.

Another thing is that he measured the amount of choreographic information that he gave to the audience. It’s akin to what Balanchine said about a ballet being like a well-prepared meal. What he gave to the group and to secondary characters and to the ballerina was perfectly measured.

His musicality is a subject for a whole book. There are countless examples of how when the music changes, he continues the same step, to give it a little bit of a different color. Or when the music stays the same, he’ll repeat the step 3 times or 7 times, but for the last beat he’ll introduce a new idea, which will continue into the next phrase. It’s absolutely fascinating.

© Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

MH: About the notations: Petipa didn’t believe in them, Arlene Croce called them “a dinosaur skeleton,” “inert theatre.” How do you see them?

AR: I think the notations contain a huge amount of first-rate choreography by the master who created our classical ballets, waiting to be used. It really excited me and gave me courage to spend time alone with them.

But learning to decipher the notations is something that happens before you go into the studio. When you go into the studio it’s live theater, like any other ballet that I choreograph. It all depends on how you inspire dancers.

If they full-heartedly believe in it like we do, we can find a style that is so refined, so unlike what we see today. It reminds us of what has been lost. Because art is not only progress; art changes and some things are lost. Like for example so much small footwork is gone. It’s not used by choreographers. It has given me so many ideas for my own works.

MH: Do you consider reconstructing these ballets to be a creative act?

AR: A reconstruction is a skeleton until we find a real nerve in it. And that’s up to us stagers as much as the dancers.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

From Marina Harss interview: “Alexei Ratmansky – Simple and Wise, a Q&A about Ratmansky’s Sleeping Beauty for ABT“

I feel the responsibility of our generation to work with these notations and see for ourselves what they contain. It’s such a tragedy that Sergey Vikharev is no longer with us because I want to ask him questions about his reconstructions. I dont know what his answers would be.

MH: So, why does Petipa matter?

AR: He understood that ideal geometry is what the audience reads the best. Circles, squares, lines, diagonals. He spent his life refining this geometry. And he was one of the strongest minds and masters in our art. We need to understand, finally, what is Petipa, what is his choreography? I’m much less interested in what Vaganova thinks of Petipa or Konstantin Sergeyev thinks of him than in his own work. So, until we know what steps really are Petipa I think we should keep working on it.

Thank you, Marina. That must have been a most exciting event. Ratmansky gave two sets of classes with the Petipa style at the Jackson Competition, 2018, and then a conversation with John Meehan where I am certain he discussed some of the material you have shared. I also suspect the Harvard event went into more detail than Jackson, given the sponsorship.

Thanks again.

Thank you for reading and commenting, Renee.

Thank you for this fascinating interview. I’m really looking forward to seeing Ratmansky’s Sleeping Beauty at ABT this year and have read so much pro and con about it.