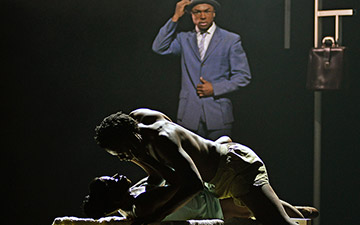

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

29 May 2019

www.nycballet.com

davidhkochtheater.com

Into the Woods

As we all know, balletomanes are a fractious bunch, more than willing to argue to the last breath over the superiority of this or that dancer, choreographer, or production. And no balletomaniac discussion is more energetic than the one that often breaks out between lovers of George Balanchine’s and Frederick Ashton’s renditions of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But really, how can one choose one over the other? My personal favorite is whichever I’m watching at that particular moment. Both choreographers (who created their versions only two years apart, in 1962 and 1964) seem to have been deeply stirred by Mendelssohn’s irresistible score and by Shakespeare’s depiction of tenderness, jealousy and folly in both the fairy and the human realms.

As it often does, New York City Ballet is closing out its spring season with a run of Balanchine’s Midsummer. It is, really, the best way to move into summer, one’s eyes filled with the afterimage of dancing fireflies and fairies – children from the School of American Ballet – streaming across the stage. There are dozens of them, fluttering their arms vigorously, running in circles, spinning on their own axis, electrifying the space around the adult dancers. Like the enormous Christmas Tree in his Nutcracker, the beautifully-rehearsed mayhem in Midsummer is one of Balanchine’s great theatrical coups.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

And so is the fleetness of the storytelling. Where Ashton pays more attention to details of characterization, and, in the end, takes the relationship between his fairy king and queen very seriously – cue one of his most rapturous pas de deux – Balanchine keeps things light. Taking Mendelssohn’s lead, he moves fluidly, seamlessly from one scene to another, cleverly employing cinematic techniques like blackouts, cuts, and dissolves to keep the action moving. In the opening, he jumps from the fairy realm to the human one, finally bringing them together for just one moment, on the final notes of the overture. Puck holds a leaf out to the unhappy Helena as she walks despondently through the forest. She takes the leaf – Puck remains invisible to her – and holds it to her lips, lost in thought.

For Balanchine, Shakespeare’s characters are two-dimensional types, exemplary but wholly unreal. They are shadows in a shadow-play, representing this or that quality: Oberon’s imperiousness, Tatiana’s glamour, Puck’s impishness, Lysander’s inanity. The first act emphasizes rhythm and timing in the storytelling and the dancing. The one exception to this fleetness is the lengthy and insipid pas de deux for Titania and her cavalier. But the secret of the ballet is that Balanchine saves the real emotion for the second act, after the story has been told. (Ashton’s ballet contains one act, Balanchine’s two.) The setting of this second act is formal: a wedding celebration set to various bits and pieces of Mendelssohn. But the seemingly light divertissement culminates in a pas de deux so limpid, so exquisitely delicate that it appears to encapsulate Balanchine’s deepest thoughts about love and the possibility of harmony in the universe.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Set to the Mozartean andante from Mendelssohn’s Ninth Symphony – composed when he was just fourteen! – it unfolds like a long, sustained aria, repeated twice with slight variations. The two dancers are like planets in orbit. The man walks around the woman, holding her by her fingertips as she revolves in arabesque; meanwhile she traces smaller circles within the circumference of his path. Halfway around, they switch hands. Together, they are like the moving parts in a clock. Later, he assists her, with the lightest of touch, in little jumps in which her legs kiss in the air; each time, she hovers for just a moment. Finally, he raises her from a tilted position slightly behind him, upward and upward until, after a moment of suspension in perfect balance, he allows her tilt forward, in free-fall, only to catch her at the last moment with his other hand. The heart catches.

At the May 29 performance, the divertissement couple (it has no other name in the program) was danced by Sterling Hyltin – a dancer of great delicacy, pinpoint precision, and lightness – and Amar Ramasar. They performed the pas de deux with a gliding quality, attuned to each other’s rhythms and quality of movement. Ramasar recently returned to the company after being caught up in a scandal related to the exchange of pornographic images. Many feel he should not have been allowed to return. But his dancing here made a case for his place in the company: the extreme care and concern with which he handled Hyltin in this tender scene, her total trust in him. The values represented by the ballet itself – its emphasis on partnership and respect and collaboration – are an example of the way, ideally, humans can and should treat each other. May it show him the way.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The rest of the cast was strong, led by an excellent Harrison Ball as the mischievous Puck. Ball’s dancing has a wonderful clarity and power. Instead of reverting to the cute and sprightly idea of Puck, he takes the role into a stranger and more interesting terrain, creating beautiful, angular shapes in the air and interacting with the other characters with a deadpan, almost ironic, humor. The imperious Oberon, traditionally danced by a shorter male dancer – the originator of the role was Edward Villella – was danced here by the boyish Anthony Huxley, replacing an injured Gonzalo García. The role suits him perfectly: noble, almost inhumanly precise, quick, and elegant. The notoriously difficult scherzo allows him to show every beaten jump in the lexicon: brisés, split jumps, bent-legged jumps, entrechats, backward-moving jumps. Often he seems to hover just above the floor, like a hummingbird.

I found Sara Mearns’ Titatiana a tad forced, more muscular than majestic, and lacking in the glow that makes this role so luminous in the right hands. She has a tendency to power through choreography, often to thrilling effect, but here that drive tended to obscure details in the choreography. As the lovers, Lauren King, Erica Pereira, Lars Nelson, and Daniel Applebaum had excellent comic timing; but it must be said that Balanchine’s choreography for them is implacable. I’ve never seen a bad cast. Silas Farley was a benevolent Theseus; Georgina Pazcoguin a fiery Hippolyta, excelling in both the jumps and the fouetté turns that fill the role. Russell Janzen, as Titania’s nameless cavalier, danced with his usual elegance and superlative partnering finesse. For such a tall dancer, he is also an excellent turner, calm, relaxed, and regal. Kristen Segin, lead Butterfly, flitted and spun with enviable lightness.

I wouldn’t trade the production for any other, and I feel the same about the Ashton. I promise, it’s OK to love both.

Marina Harss’ analysis and appreciation is simply glorious, and undoubtedly spot on.

Dance Tabs is VERY lucky to have her review.

We are very lucky indeed! (Ed)

Renee, you are too kind!

No she’s not – statement of fact! (Ed)