© Sophie Garcia. (Click image for larger version)

Faso Danse Théâtre

Kalakuta Republik

★★★✰✰

London, Barbican Theatre

30 May 2019

www.fasodansetheatre.com

www.barbican.org.uk

Although named after Fela Kuti’s compound, which housed his family, followers and a recording studio, it is a puzzle to piece together the dance sequences into anything that could be regarded as biographical; especially when, like me, one has only a cursory knowledge of the Nigerian musician and political activist who died mysteriously, in 1997. More than 1m Nigerians are said to have attended his funeral.

In 1970, Kuti declared the original Kalakuta Republik an independent free state from the military junta that ruled Nigeria, and it survived, despite frequent raids, for seven years before being razed to the ground by soldiers, during which invasion Kuti’s mother suffered fatal injuries. Soon after this tragedy, Kuti simultaneously married 27 women made homeless by the attack, many of whom were his back-up singers. He told a newspaper some time later that he did not have sex with all 27! On one hand, as for example viewed by this dance theatre, Kuti was a heroic political activist, courageously standing up to a barbaric and corrupt regime, but at the other end of the spectrum (enhanced by the imagery of the compound and marrying his followers) he can be imagined as a cult leader.

© Doune Photo. (Click image for larger version)

Kuti was the pioneer of Afrobeat, which merged Ghanaian and Nigerian music – such as highlife – with jazz, funk, rap, dancehall and reggae to produce a big band sound, heavy on brass and percussion, that is often repetitive and hypnotic. That sound, mixed into a long, meandering score by Yvan Talbot was both the best and worst of the evening: marvellous high points in great bursts of rhythm and harmony – at times it rivalled the best smooth jazz – before getting stuck in relentless sequences of wearisome tedium.

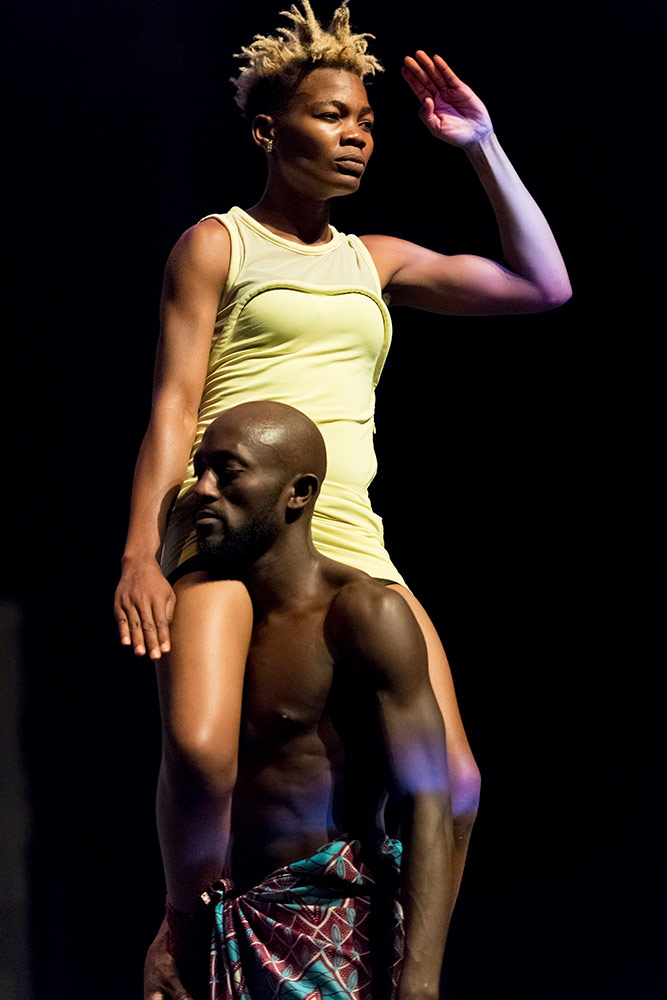

The stage was dominated by two large screens that showed, intermittently, large slogans of no great insight (‘All that Glitters is not Gold’, said one; another, ‘Decadence can be an end in itself’) and grainy, indistinct film. A 70s-style tan leather sofa with squashy cushions, a portable box for recording equipment and several plastic-backed metal chairs were also key to aspects of the performance: both as platforms and as places of refuge and sexual encounter. Between acts 1 and 2 the sofa was covered in white powder, which billowed everywhere; and in the second act, the chairs were stacked into a huge mushrooming tower on one man’s back before they collapsed all over the stage. At the show’s finale when the dancers (each woman sitting astride a man’s shoulder) marched slowly and soulfully off the stage and across the front of the audience to the exit door, they left behind a mess akin to a teenage party when the parents have gone away.

© Doune Photo. (Click image for larger version)

The dancers had remarkable movement quality. Six of the seven were African, variously from Burkina Faso, Cameroon and the Ivory Coast, one of whom, Adonis Nébié, seemed to portray Kuti, mostly separated from the others, wearing jacket and trousers and (in act 2) with half his face painted white. These dancers feel the music in a unique way, the movement channelled internally, pulsating under their flesh. The seventh dancer was Marion Alzieu, formerly with Jasmin Vardimon Company and credited as a co-creator of this piece (assisting Serge Aimé Coulibaly, the company’s founder). Her movement style was more fluid, balletic and superficial than the African dancers, a contrast that turned her own solos into refreshing interludes.

That said, without help, which was certainly not forthcoming in the programme, most of the action was a mystery in relation to Kuti and the Kalakuta Republik. Why the white powder? Why did the dancers routinely lift their vests and dresses to reveal skin? Why did the three women strip to their underwear? What was the point of the slogans? Why build a tower of chairs? There are so many more questions. I know that many will say that it is not necessary to know these answers, if indeed there are any, but to me it is as infuriating as a partly finished puzzle. So, whilst accepting that this work concerns matters that are largely alien to my cultural appreciation, I found myself largely perplexed by the narrative and any intended characterisations; albeit often hypnotised by the music and always in awe of these great dancers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.