© Maria Baranova. (Click image for larger version)

Joyce Ballet Festival – Program B

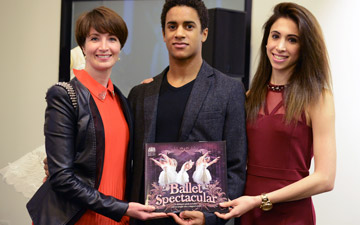

Curated by Lauren Cuthbertson with dancers from The Royal Ballet, National Ballet of Canada and American Ballet Theatre

Darl, Seventy Two Hours, Two Sides Of, Reverie, Dialogue Dances

★★✰✰✰

New York, Joyce Theater

10 August, 2019

www.joyce.org

www.roh.org.uk

I was rereading the program for The Lauren Cuthbertson Show at the Joyce and realized to my horror I remembered nothing about one of the pieces, not even that I had seen it. Cutting myself some slack, I decided this says as much about Cuthbertson’s curatorial sensibilities as it does my apparent semi-senescence, and, also, there’s my lead.

Actually, this wasn’t The Lauren Cuthbertson Show, rather Program B of the Joyce Theater’s annual Ballet Festival, this year featuring a raft of Royal Ballet dancers and guests, and four programs curated by Royal Ballet personages. I hadn’t seen much of the well-regarded Cuthbertson, so I was looking forward to this chance to get to know her (she appeared in four of five pieces), as well as the not-always-dubious introduction to new works by new choreographers, as every item on the program but one was a world premiere, with the other a U.S one, and, with one exception, by choreographers entirely new to me.

I left the (happily short) program with questions. Had Cuthbertson chosen these pieces to show herself off as a performer of depth and facets? As a leg up and New York exposure for up-and-coming choreographers? Or was this program simply a fortuitous confluence of scheduling and availability which seemed like a good idea at the time? Whatever she’d intended, I left the theater with an impression of a powerful if conventional artist of no little brilliance, yet a cipher within. I also left wishing that I’d had a chance to see her in first-rate choreography.

© Maria Baranova. (Click image for larger version)

The program got off to a cute start with Jonathan Watkins’ Darl, with the lithe Cuthbertson standing in fashionable practice attire (costumes by Lauren Cuthbertson), tugging the heel of a toe shoe into place, her dance bag and other accouterments stowed nearby. As we listened to a recording of Cuthbertson and Watkins wisecracking and brainstorming about what she should actually do, she bourreed about, enacting the pair’s suggestions perhaps less wittily than they might have imagined, the “score” augmented with occasional soundings of Hanna Peel’s “Rethinking Bolero,” (far after Ravel), and meandering vocal asides. Geek that I am, what stuck most was Cuthbertson (I think) having to restart a router (presumably hers) because her smart thermostat wasn’t showing up on the Internet — an everyday problem with which everyday folk are sure to identify. As much as I would have loved seeing Cuthbertson’s impression of rebooting hardware, this, alas, was not among the movement motifs being bandied about, but some color perhaps intended to banish the ballerina mystique, bring us backstage, and show that, at heart, dancers are people much like you and me. Of course, they aren’t much like you and me, or we wouldn’t be sitting in theaters paying exorbitant sums to admire them onstage, and Darl just exchanges one artificial conceit for another (which, I might add, has been done to death). I am, perhaps, devoting more time to thinking about this bit of fluff than its creators did to making it; it was, at least, brief and harmless.

It was also an effective, if casual, showcase for the qualities of Cuthbertson’s dancing we’d see again and again throughout the program. If I had to describe her in two words, they’d be clarity and reticence. Every gesture, even the smallest, is shaped and phrased with care: precise, but without ostentation. She bourrees as if nonchalantly bestrewing the stage with jewels. She’ll show you a glorious leg in attitude, curved just so, and no more, horizontal with perhaps a hint of winging to show she could go much, much higher if she felt like it; she wouldn’t be caught dead in an “attabesque.” Also, when she moves, she moves; when she’s at rest, she’s at rest. Every choreographer on this program employed, to one extent or another, her near instantaneous transitions between stage-devouring speed and stillness. You’re hardly conscious of her acceleration; she’s just there, and then elsewhere. There’s an affecting honesty here, which speaks of great respect not only for her art, but for whatever task of which she might find that art requires. I imagine her being popular among choreographers as she does a bang-up job of bringing their visions to life. Powerful, modest, but never prim, she’s an archetype of the English ballerina, or at least this American viewer’s conception of one.

And yet. However much I admired her clarity and reticence, they can take one only so far and no farther; perversely, I found myself wishing her to transcend these qualities which she so beautifully embodies — to draw her excellent lines while also, at least sometimes, coloring outside them. A wit on Twitter (ok, it was me) wrote, with less hyperbole than it might seem, of her taking flaming adequacy to heretofore unimagined heights. Selling is not always vulgar, and a dancer can inhabit space with vision and imagination as well as classical purity. Were the specter of Balanchine ever to utter to Cuthbertson his famous exhortation to reach as if for an ice-cream cone, one imagines her answering with “which flavor?”

© Maria Baranova. (Click image for larger version)

Anyway, back to the program. Gemma Bond’s Seventy Two Hours was considerably briefer than its title might suggest, a lightweight dance by American Ballet Theatre’s Devon Teuscher and Aran Bell, which took a cerebral approach to its accompaniment of Rachmaninov piano preludes. Teuscher and Bell drifted dispassionately about the stage, singly and together, reacting to dramatic musical passages with steps which might embody that emotionality if not for their muted affect (Bond is fond, it seems, of giving Teuscher swooning backbends delivered with almost classical serenity). There wasn’t much emotional engagement between the pair in their adagios, but collegial confluences of support needed and offered (and prettily, too). Bond’s gentle contrariness to her score gave this piece a hint of metaphorical sweet and savory almost tangy enough to justify watching it.

The presence of Marcelino Sambé with Cuthbertson would almost, in itself, have been reason enough for Juliano Nuñes’ Two Sides Of. This conventionally acrobatic pas de deux had Cuthbertson twisting frequently up, down, and around the stalwart Sambé, her line impeccable in even the most unlikely of contortions. Though Cuthbertson was the star of their adagios, my eye kept drifting back to the charismatic Sambé, the calm center of their gyrations, drawn by the intensity of his focus on his ballerina. It was intriguing. In a very brief diagonal Nuñes gifted us with the pair performing a single, soaring grand jeté together, and it was like a visitation from Olympus. I could have happily called it a night after this glorious moment, and perhaps I should have.

Stina Quagebeur’s Reverie saw Cuthbertson making her ungainly costume, also by Quagebeur, of tank top, flouncy skirt and unflattering ankle socks, look far prettier than it had any right to, as she noodled about to Kate Shipway’s playing of Debussy’s Reverie L.68 for piano. Cuthberson’s dynamic range and aforementioned clarity did more for this familiar yet forgettable (yes, this is the one) piece than it did for her. Think of an Isadora Duncanish meditation without the drama, charm and petals, and whatever else made Duncan interesting, and you’d be about right.

© Maria Baranova. (Click image for larger version)

With cultural appropriation being such a hot topic these days, I am at a bit of a loss about what to make of Dialogue Dances, with choreography by the National Ballet of Canada’s Robert Binet, dramaturgy (yikes) by Jessica Schacht, set to selections from Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa, the tenor Jeremy Dutcher’s album of arrangements and recordings of traditional music by the Canadian Maliseet First Nation, of which he is a member. Before the piece began, the dancers, mostly from the National Ballet of Canada, passed around a microphone and told us, with earnest artlessness, how privileged they were to be dancing to this First Nation music. Was this even more cringeworthy and self-congratulatory than Cuthbertson’s and Watkins’ chatty score for Darl, or a sincere and appropriate expression of cross-cultural respect? I throw up my hands and leave this determination to the reader. Once the piece began, I did admire Binet’s decision to approach Dutcher’s music with a purely balletic vocabulary rather than attempt to blend it with trappings of indigenous dance (which seldom turns out well). It wasn’t hard to read the white gauzy clouds in which Desmond Tait’s designs clothed two of the dancers as representing Dutcher’s oft-referred-to Maliseet ancestors, or First Nations ancestors in general, a conceit which Binet wisely applied with a delicate, if conventional, hand. Xiao Nan Yu was notable as a gauzy ancestor, while Cuthbertson, all in black, fited seamlessly into the choreographic gestalt, as might have been expected. In all, Dialogue Dances pleasantly and deftly navigated the cross-cultural minefield, avoiding the respectful sepulcher in which such endeavors risk entombing themselves. I did, however, find myself wondering how Binet might have fared had he more directly addressed Dutcher’s complicated vocal rhythms, or rather what could be have made of them given the singer’s fondness for Bocellian levels of reverb.

As I said, I left the Joyce with questions, answered mostly in the asking, and also with a hankering to rent the video of Cuthbertson’s star turn in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which I might just as well have done in the first place.

Simply great to see Eric Taub in print again -technology et al. Do it more often, Eric.

You’ve been missed, despite the interesting Facebook notes about Boris.

Believe it or not, one prefers to hear more about what actually happened than about your personal feelings on the matter. As Balanchine would say, “Show, don’t tell.” This reportage felt more self indulgent than the curatorial attempts at artistry.