© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

Marlene Monteiro Freitas

Bacchae: Prelude to a Purge

★★★★★

New York, Harvey Theater (BAM)

7 November 2019

www.pork.pt

www.bam.org

Madness

Have you ever seen something that made you feel like you had no idea what was going on, and loved it all the same? I have. Just last night, in fact. It was entitled Bacchae: Prelude to a Purge, by the Cape Verdian artist Marlene Monteiro Freitas, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Freitas has been active for over a decade and made a piece last year for Ohad Naharin’s Batsheva Dance Company, but this was her US début, and certainly the first time I’d heard of her.

How does one describe Freitas’s Bacchae? Well first of all by saying that it has very little to do with the action in Euripides’ tragedy. Hints of Euripides’ themes emerge here and there, as when a blind man is led to the stage (Tiresias). A short black-and-white film of a birth evokes the birth of Dionysus to a mortal woman – notably it is the one serious, almost reverent, moment in the evening. Then there is the constant thrum of Dionysian ritual, intensified by the grotesque, mask-like expressions worn by the performers. In one, gorgeous moment, they become a chorus. If the performers could get away with tearing each other to shreds, like the Baccantes, they just might do that as well.

What this Bacchae resembles most is a kind of carnaval, an ordered mayhem in which up is down, all inhibitions are shed, and madness reigns. The performers include: five trumpet-players who also dance, seven dancers (including Freitas) who also sing and speak, and one narrator/percussionist who also dances and sings. For a little over two hours (with no intermission) they dance and shout, make faces, manipulate props and their own bodies, emit strange sounds. What emerges is something one doesn’t see every day: an explosion of vitality, irrationality, compulsion, monstrosity and pleasure.

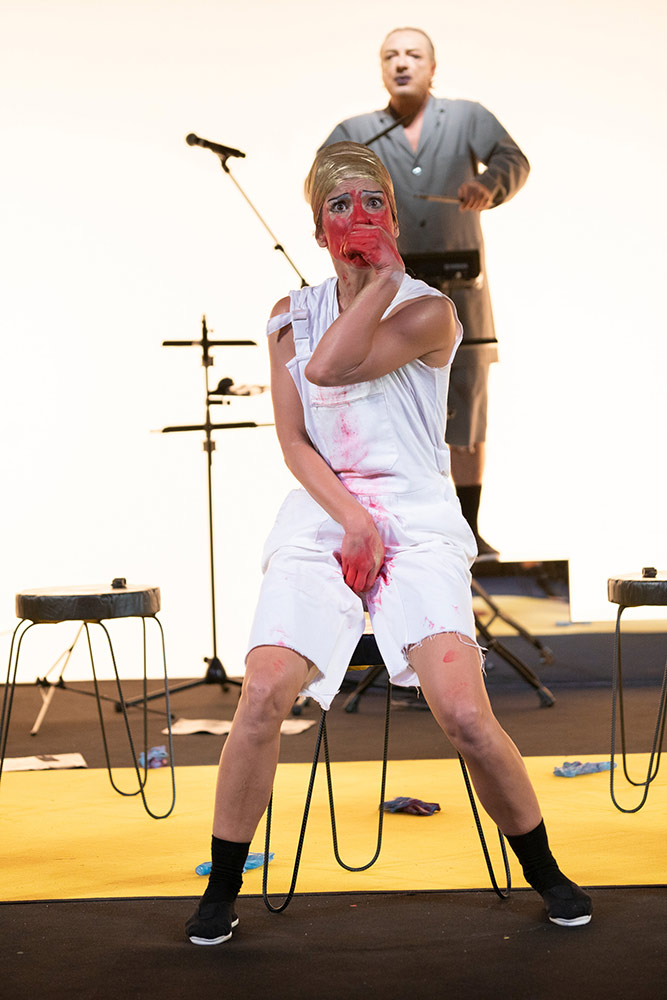

Let me set the scene: on the Harvey’s bare stage, a bank of stools, a bevy of music stands, a mirror, and a small platform in the rear. The performers (dancers and trumpeters) are in simple, white or blue work clothes and sneakers. The dancers’ makeup – exaggerated smears of lipstick, sloping downward, dark circles around their eyes – emphasizes their already unhinged expressions. How do they make their eyes bulge out of their sockets, and maintain that expression for the entire duration of the show? They must all have terrible headaches afterwards. The music-stands become a million different things: masks, typewriters, fake penises, hobby-horses, rifles, torture machines.

© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

As in a parade, the performers walk, dance, and do their individual tricks, all while stepping off and back onto the stage in a constant stream. The trumpets blare, or suddenly break into a delicate passage from Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun. The musical choices are consistently clever and surprising. At one point, the trumpets play a version of the classic Joao Gilbert bossa nova tune Desafinado; the dancers respond with kazoo-like instruments made from a horn attached to a long hose. Later, to a Satie Gnossienne played in the style of a Greek folk tune, Henri Bertrand Lesguillier (the narrator/percussionist) does a sinuous, seductive little dance. Another man unleashes an unhinged belly dance that becomes a chest dance, a shoulder dance, a butt dance. Someone shouts out the Pasolini poem “Io sono una forza del passato.” (“Mostruoso è chi e nato dale viscere di una donna morta” – he who is born of a dead woman is a monster.) It all leads to a euphoric, ecstatic rendition of Boléro, which, I must say, is the best Boléro I’ve ever seen.

What is most impressive is that none of this feels random or self-indulgent. There is rigor, and a sense of order and ritual behind this madness. Even at over two hours, the energy flags only slightly in the middle. Could they cut 15 minutes? Probably. I felt a deep admiration for Freitas’s seemingly inexhaustible imagination, and that of her performers. What emerged from this mess of compulsive behavior was a crazy kind of beauty.

You must be logged in to post a comment.