© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Coppélia

★★★★✰

London, Royal Opera House London

28 November 2019

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.roh.org.uk

Coppélia was the first full-length ballet that Ninette de Valois staged for her early Vic-Wells Ballet in in 1933 (full-length then being just two acts). She danced the leading role of Swanilda herself, after opening performances by Lydia Lopokova. The production was staged by Nicholas Sergeyev, former régisseur of the Imperial Ballet. He had brought notations of the version choreographed by Marius Petipa in 1884, revived in 1894 and adapted by Enrico Cecchetti. (The original 1870 ballet had been created by Arthur Saint-Léon for the Paris Opera Ballet, with the role of Franz played by a female dancer en travesti.)

De Valois and Sergeyev added a third act for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1940, mentioning Lev Ivanov as yet another choreographer. There appears to be no evidence, however, that Ivanov had much to do with Coppélia, though the Royal Ballet production now credits him, Cecchetti and De Valois, with no mention of Petipa. Why not? A mystery, since the Bolshoi’s reconstruction of Coppélia, researched by Sergei Vikharev from the Stepanov notation, attributes the choreography almost entirely to Petipa.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The Royal Ballet’s current revival, after 13 years’ absence, is based on De Valois’s 1954 production, with designs by Osbert Lancaster. Anthony Dowell brought it back in 2000 when he was artistic director of the RB. Far more widely seen in the UK over the years have been Peter Wright’s production for Birmingham Royal Ballet and Ronald Hynd’s for English National Ballet. This year, Coppélia makes a very welcome alternative to the RB’s usual Christmas offerings of The Nutcracker or Cinderella, with rewarding roles for the company’s dancers, as well as the return of Délibes’s delicious score.

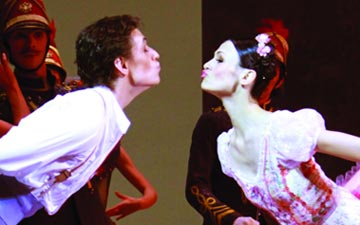

Lancaster’s folkloric designs are gaily colourful, with appliqué details on the costumes and a fine array of hats, boots, full skirts and tutus. Francesca Hayward as the first night Swanilda makes her appearance as a village belle in a pretty peasant costume. Looking for her fiançé, Franz (Alexander Campbell), she tries to attract the attention of a girl – the doll Coppélia – sitting high in a window. When there’s no response, Swanilda addresses her bewilderment to the audience, introducing us to the ballet’s convention of graphic mime. The gestures are timed to the music, which speaks for the characters as well as expressing their inner emotions. (Tchaikovsky greatly admired Délibes’ skill at composing for ballet’s requirements.)

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Swanilda catches Franz gazing up adoringly at mute Coppélia, and then flirting with a red-blooded czardas dancer (fiery Mayara Magri). He feels entitled, whereas Swanilda suspects he’s untrustworthy. She tests their relationship by shaking a head of wheat, a custom similar to Giselle’s petal plucking, and finds Franz wanting. He has already proved he’s heartless by catching and pinning a butterfly to his lapel, presuming Swanilda will be charmed. He has failed to appreciate that although she dances as swiftly and lightly as a butterfly, she is not going to be so easily subdued.

Hayward flits across the stage in brisés volés and hops on pointe with insouciance (apart from a few hiccups in Act III). Her footwork is sparkling, fleet and neat, her arms eloquent, her head tilted just right. She’s a good foil for her girlfriends, a motley crew of different heights and abilities (unlike the Bolshoi’s matching sextet). Hayward’s comic timing to the music is perfect in Act II, from her mockery of Franz for not realising that Coppélia is a doll to her callous teasing of besotted Dr Coppélius in his workshop.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Gary Avis, physically transformed as the doddery doll-maker, is zany rather than crazy and crotchety. He has created his own world, with mechanical Coppélia (Ashley Dean) as his surrogate daughter, surrounded by automata playmates. He longs to bring her to life, and Franz’s invasion of his property provides him with the chance to do so. Avis invests his would-be sorcery with real intensity, overcome with delight when it appears to work. Hayward is delectably perky wearing Coppélia’s red ‘pancake’ tutu, tiptilting it as she appears to slump into inertia. Avis is nicely shocked at her impudence.

There’s a telling exchange of mime between them when Coppélius tells her proudly that he made all the figures she has seen in his workshop. “What about him, then?” she asks, pointing at the drugged figure of Franz. Like a politician, he distracts her instead of replying, encouraging her to dance far better than his clockwork dolls. She revels in her naughtiness, breaking his heart when she obliges him to realise that his Coppélia is just a lifeless puppet after all.

By the end of Act II, the ballet is really about Dr Coppélius’s plight. Avis has won all our sympathy for the destruction of the old boy’s dreams. He has to be banished soon after the start of Act III, paid off so that the emphasis can return to the young lovers. Avis sits in the window of his workshop, drowning his sorrows and celebrating on his own the marriage of Swanilda and Franz, surrounded by villagers.

The RB’s version of the last act makes little sense. It’s meant to be a festival in honour of a new bell presented to the town by a local dignitary, with allegorical figures representing various activities during the day. In this production, who can tell what’s going on until it is time for the wedding pas de deux.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Délibes provided attractive music for a Masque of the Hours – dawn, morning prayers, midday and night. The Bolshoi version has an elaborate ensemble of 24 dancers in blocks of six, dressed in different colours for the times of day. The RB breaks the hours into separate groups of eight, appearing at unaccountable intervals. In between comes a sparkling solo for Aurora (Dawn), radiantly danced by Fumi Kaneko, and a piously sustained one for Prayer (Itziar Mendizabal). A group of women with scythes may represent Work, while music intended for Peace has been appropriated for the wedding pas de deux. Music for War or Discord is given to Franz for his only chance to show off in a solo. (Sergeyev claimed that it was his choreography – who knows for sure?)

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Franz and Swanilda emerge from the village church for a formal pas de deux similar to that for Aurora and her Prince in The Sleeping Beauty. Swanilda’s repeated promenades in arabesque are almost as challenging as Aurora’s balances in the Rose Adagio. Hayward shows that mischievous Swanilda has matured into a woman in love, confident that her partner will support her in their marriage. She dances her solo adorably, keeping the momentum flowing through syncopated pauses. Campbell’s Franz is still a likely lad, bounding irrepressibly through his virtuoso solo, but he has learnt his lesson: his head won’t be turned by anyone else.

The dancing is so enjoyable, the comedy so appealing, that any flaws in the story telling (and first-night ensemble dancing) are easily overlooked. Less forgivable was the playing of the brass section of the orchestra, under Barry Wordsworth’s baton. Délibes deserves better. Let’s hope all will be sorted for the live relay in cinemas on 10 December, with Marianela Nunez, Vadim Muntagirov and Gary Avis in the leading roles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.