© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Marina Harss’ Completely Off-The-Cuff, Un-Scientific List of the Year’s Memorable Performances…

I don’t really believe in lists, but it’s admittedly fun to look back over the year and reflect on moments that have stayed with me. So here they are, in no particular order…

1) Where to begin? Perhaps with the show that puzzled me the most: Marlene Monteiro Freitas’s Bacchae: Prelude to a Purge at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I’m still unsure of what it was supposed to be, or how it relates to the rest of Freitas’s work, but this carnival-like reinterpretation of The Bacchae managed to evoke the strange magic and mayhem of Bacchic ritual while cleverly weaving images and themes from Eeuripides’ tragedy in a way that was entertaining, completely engrossing, and that seemed to combine rigor with madness. Its range of disparate elements included masks and trombones, a hypnotic rendition of Ravel’s Boléro, a poem by Pasolini, and a sequence in which one of the dancers, clutching a music-stand, seemed to repeatedly take aim at members of the audience. Even so, this Bacchae never felt indulgent or chaotic, and the dancers were riveting.

My review is here.

2) This year, Bijayini Satpathy, a star of the odissi ensemble Nrityagram (based near Bangalore), struck out on her own with a solo show, Kalpana, at the Drive East festival. It was her first time performing alone, and it took her a year to prepare. In an interview, she expressed her misgivings and fears about leaving the comfort of her work with Nrityagram’s artistic director and choreographer Surupa Sen. What emerged from the soul-searching was a gripping artist capable of filling the stage with her personality and her powerful technique – I can still see her smooth transitions in my mind’s eye – which drew the audience into her vibrant inner world. Over the course of an hour and a half, she became Krishna as a child, the demon Ravana, and even a magic deer running through the woods. It is a performance I will not soon forget.

© Anubhava. (Click image for larger version)

My review is here.

3) Yes, another Indian-dance show. There is so much good Indian dance in New York, thanks to various festivals, including Dancing the Gods and Drive East. After an absence of several years, Shantala Shivalingappa returned to New York with her solo evening Akasha, accompanied by her four excellent musicians – they all performed onstage together at the Joyce. One of the qualities I love in Shivalingappa’s dancing is the purity of her movement. She doesn’t gild the lily – there’s a kind of sparseness to everything she does. And those jumps… She springs into the air like an antelope, taking your heart with it. Like many of her shows, Akasha has a beautiful ending. In silhouette, she poses, like a stone carving, her profile pristine against a blue background. Only her hands move, vibrating, mirroring the vibrations of the drum…

© Elian Bachini. (Click image for larger version)

My review of the performance is here.

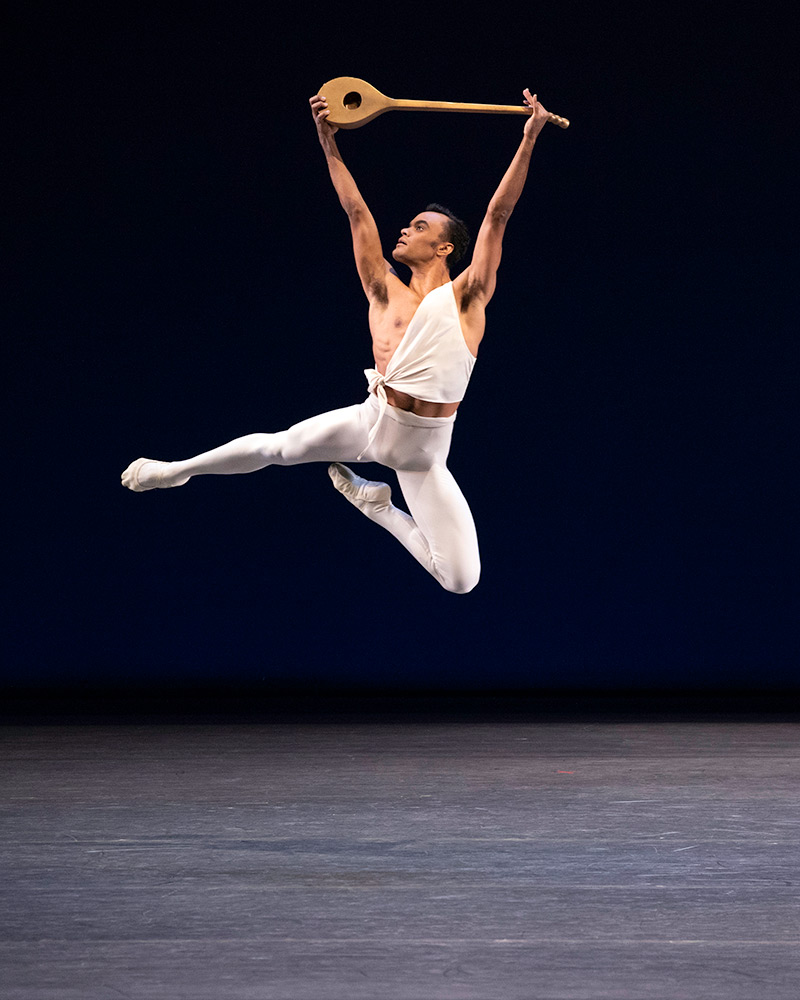

4) The problem with acknowledged masterpieces like George Balanchine’s Apollo is that we see them too often. It can be hard to feel something when we attend a performance, even a very good one. And then we see something that makes us reconsider how it can be done. Taylor Stanley’s début as Apollo at New York City Ballet, in January, felt like one of those occasions. He’s not a typical Apollo, at least not as it is performed today: he’s not tall, not commanding, not statuesque. Instead, his rendition emphasized the questioning, probing, even experimental side of the young Apollo. His relationship to his three muses was almost that of student to his teachers. Stanley’s gentleness brought a new and different sensitivity to the pas de deux with Terpsichore. This is not to say that Stanley’s début was better than Calvin Royal’s or Herman Cornejo’s, both of which also took place this year, but his was the most interesting, internal approach to the role I’ve seen in a long time. For the record, my benchmark is still Nikolaj Hübbe at his farewell.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

At that same performance, Gonzalo García danced the role of Orpheus in Balanchine’s seldom-performed ballet of the same name. I found him really touching in this deeply melancholic, almost Graham-esque ballet. García is a funny dancer who doesn’t rise to the occasion in every role. He has inherited much of the Joaquin de Luz’s bravura repertory, but he doesn’t have De Luz’s spark and there’s a slight strain in his dancing in these roles. However, in enigmatic pieces like Orpheus (he has long been a favorite in Jerome Robbins’ Opus 19: The Dreamer), García acquires an aura of poetry and lyricism no other man in the company has. A few days after Stanley, he danced a quietly lyrical Apollo, too.

My review of Taylor Stanley and García is here.

5) It’s always a party when the Danes come to town. This August, Ulrik Birkkjaer, a former Royal Danish Ballet (RDB) principal dancer now with San Francisco Ballet, brought an ensemble of RDB dancers to the Joyce, where they performed a program of excerpts from ballets by the Danish choreographer August Bournonville. While it wasn’t quite the revelation their previous visit, in 2015, had been (Gudrun Bojesen has since retired), the dancers reminded us of how natural, and human, and joyful, this Romantic style can be. For me, the highlight was the pas de deux from The Kermesse in Bruges, in which a young man declares his love for a young woman by dancing with her in the town square. At various junctures the two young lovers look to the people around them for support and encouragement. The couple is part of a larger world, made up of regular people. The duet was beautifully danced, by Jon Axel Fransson (a new principal) and Stephanie Chen Gundorph.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

My advance piece on Bournonville is here.

And my review of the evening is here.

6) If you had told me a year ago that I would be listing a ballet by Maurice Béjart as one of the top performances I would see in 2019, I would have been very surprised. But there it is. Songs of a Wayfarer, set by Maina Gielgud on the dancers David Hallberg (of ABT) and Joseph Gordon (of NYCB) as part of the Joyce Ballet Festival, was like a bolt of lightning. Some of its power came from the music, Mahler’s song-cycle about a young man finding his way through life while shadowed by his destiny. And from Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s rough-hewn, wounded voice on the recording. The choreography is relatively simple, straightforward, aching, sustained. (And yes, a bit emphatic, in that Béjart way.) Joseph Gordon, as the young man, revealed a new side of himself, vulnerable and intense, that he seldom gets to show at New York City Ballet. The subtle eroticism worked, as well – thankfully, their performance was more understated than some of the ones I’ve seen on YouTube. After the ballet ended, with Hallberg leading Gordon away into the darkness, there was a long silence in the theater. I hope they get to dance it again somewhere soon.

© Maria Baranova. (Click image for larger version)

7) Mark Morris’s The Letter V, performed by Houston Ballet at City Center in October was an unexpected delight. Set to Haydn and dressed in breezy greens and yellows, it was an elegant, formal, almost mathematically perfect dance. (It even contains a maypole dance, though without the maypole.) The beautiful, pristine Houston Ballet dancers showed every detail in the score, every repeated phrase, every pause for breath, with ease and grace. The dance echoed the music’s classicism, while at the same time feeling completely fresh and of the moment. The mood was pastoral, friendly, with a touch of wit. And as always, it revealed that lucid inner logic that is perhaps Morris’s greatest strength. I found myself wanting to see it again right away.

© Amitava Sarkar. (Click image for larger version)

8) Tap is having a welcome comeback; just this fall we’ve seen excellent shows by Ayodele Casel, Caleb Teicher (at Fall for Dance), and Dormeshia (formerly Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards). Dormeshia’s And Still You Must Swing at The Joyce, a tap program in the form of a jazz concert, accompanied by a trio of musicians, was a demonstration of extreme sophistication and mastery of form. With her collaborators – Jason Samuels Smith, Derick K. Grant, and Camille A. Brown – Dormeshia created an impressive of dynamics and moods. Each is a great artist in his or her own right. There was no conceptual framework or agenda – just pure dance.

© AK47 Division. (Click image for larger version)

My review of And Still You Must Swing is here.

9 & 10. I end my list with two ballets by Alexei Ratmansky, one for American Ballet Theatre (The Seasons), the other for the Bolshoi (a Giselle based on archival sources). The Seasons, to music by Glazunov, represents one of the many examples of how Ratmansky’s work has been influenced by his research into the choreography of Marius Petipa. It contains actual quotations (from La Bayadère, Sleeping Beauty, and elsewhere), but also flows out of a love for the classical vocabulary and structure. The plotless ballet begins as a portrait of the seasons, but soon blends into a kind of euphoric cornucopia of steps and musical ideas. I’m particularly taken with one of its most modest moments, a tender little waltz in the “Winter” section that feels like something created for a music box. But also: the lusty folk dance in “Fall”; and a pas de deux between spring and summer in which the dancers trade steps and embellish each other’s phrases, as if carrying on a fluent conversation.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

My advance piece on The Seasons is here, and my review of the ballet is here.

The new Giselle, for the Bolshoi, is something else, an example of how, through careful study of archival sources, but also through the application of his own taste, Ratmansky creates versions of often-performed ballets that feel both familiar and new. Details have been polished, mime revivified, lost images restored. Watching it in Moscow in November felt like seeing layers of dust and accumulated habit be lifted away in an instant. Which is not to say that other versions don’t have their validity or emotional heft. Ballet’s strength lies in this constant friction between change and the return to the past. In a production like this one, you see how much is lost or changed over time, but also, how many new ideas, new interpretations are possible. Nothing stands still.

© Damir Yusupov/ Bolshoi Theatre. (Click image for larger version)

My review of Giselle is here.

Marina, thank you. What a treasure to digest at year’s end. Thanks again.