© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Three Sides of Balanchine digital season: Prodigal Son

★★★★✰

Recorded 9 October 2013

Streaming 26 February – 4 March 2021 (on YouTube)

Also Inside NYCB video of Prodigal Son coaching session (on YouTube)

www.nycballet.com

The Royal Ballet was due to revive its 1973 production of George Balanchine’s Prodigal Son before lockdown closed live performances in spring last year. New York City Ballet has offered it this spring as the first ballet in this year’s digital season, positioning Prodigal Son as a cornerstone of its repertoire – a rare early Balanchine narrative ballet.

Balanchine was 25 when he created it for the Ballets Russes in June 1929, four months before Serge Diaghilev died. The idea of a ballet based on a Biblical parable had been Diaghilev’s and it was he who decided the composer should be Sergei Prokofiev and the designer Georges Rouault, painter of religious themes. The collaboration was not an easy one, for Balanchine wanted to show how avant-garde his choreography could be, to the distress of Rouault. Prodigal Son was Balanchine’s ninth ballet for Diaghilev’s company (and his 94th since his teenage beginnings). Reviewing the London premiere at Covent Garden, shortly after the Paris season, Lydia Lopokova commented: ‘The choreographic method was the same which we have become used to in the earlier ballets of Balanchine. There were the same stylised versions of acrobatic actions and the same staccato mass movements with a wilful disregard of prettiness.’

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

This time, however, she found that he had succeeded in ‘using his technique for the expression of a dramatic motif. There is flesh and blood to this ballet and we have got back again to what the stage can never do without – dramatic action.’ Serge Lifar’s intensity in the role of the Prodigal Son was much admired, as were Felia Doubrovska’s serpentine contortions as the Siren. After Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes disbanded, Balanchine was reluctant to revive Prodigal Son until 1950, when he remounted it for his New York City Ballet, with Jerome Robbins as the Prodigal and Maria Tallchief as the Siren.

The leading roles are challenging for dancers and for audiences unfamiliar with 1920s Futuristic experiments. Classical ballet conventions were replaced with gymnastic configurations and architectural props and costumes. In Prodigal Son, a single piece of scenery serves as a fence, table, column and ship. The male corps, variously described as drinking companions or goons, are acrobatic grotesques who never perform a ballet step. At times, they resemble insects, linked in a many-legged train like centipedes, or scuttling back-to-back like mutant cockroaches.

The rebellious son is a naïve youngster who has no clue who these strangers might be. He has grown up with a stern father and two docile sisters, about whom we know nothing. The boy defies his father, claims his share of the inheritance (horns and vessels) and sets out to see the world, accompanied by two male servants. We watch his misadventures through his eyes as he bonds with the bald-headed goons, gets drunk, falls for the Siren, is robbed and abandoned. Humiliated and ashamed, he crawls home to beg forgiveness. There is no resentful elder son, as there is in the Biblical parable, and no fatted calf to celebrate his return. The narrative element is so slight that the dramatically involving element Lopokova welcomed in her review depends very much on the Prodigal dancer’s performance.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

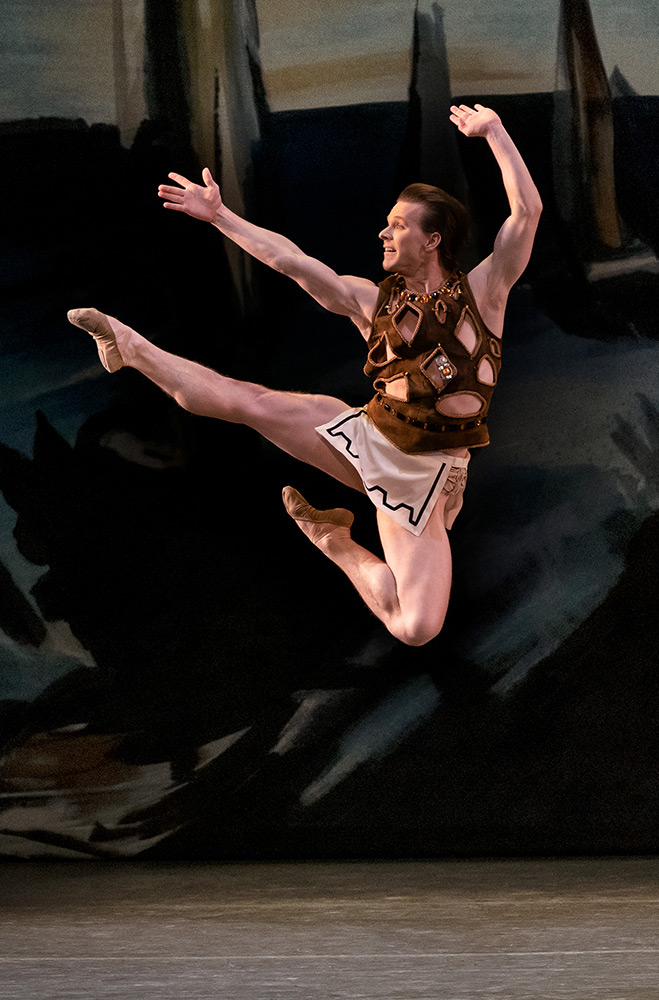

In this 2013 recording, Daniel Ulbricht starts out as a man on a mission to widen his horizons. He’s defiant rather than frenzied, not an angry adolescent out of control, as younger dancers portray the Prodigal. The skimpy costume does Ulbricht no favours: his short muscular legs look podgy, his ballet shoes too dark for his bare skin. (The recording may well be for the company archives, since the camera work is sometimes clumsy and the ending is ruined by shots angled into the wings, with stage lights and people watching the performance.) Those powerful legs, however, propel Ulbricht into big-flying leaps and sustain him upright in whirling pirouettes, knee bent and arm upraised.

He’s fine in the carousing scene with the goons, setting out to befriend them and trusting them as mates in his brave new world. He’s stupefied by the entry of the Siren, Teresa Reichlen, who pays him no attention in her opening solo. An online ‘Inside NYCB’ rehearsal session discusses the role of the Siren, with Christina Clark being coached in the solo by rehearsal director Lisa Jackson. The session reveals how complex the Siren’s co-ordination has to be in order to manage her long cloak and the extravagant positions of her long limbs. She kneels and beats her arms across her breast and back. I loved Jackson’s explanation: ‘She has interesting thoughts.’ There’s a suggestion elsewhere that the gesture might come from a traditional southern Moroccan dance by a veiled woman on her knees – could Balanchine have seen such a dance?

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Reichlen manipulates the cloak nonchalantly as an extension of herself before withdrawing beneath it, to the bemusement of the Prodigal. She is so much taller and longer legged than Ulbricht that she overpowers him, a cold-blooded serpent devouring her prey. It’s shocking when she abandons her aloofness to paw him, sit on his head and tangle her legs around his. She’s degrading a vulnerable innocent with her lewd behaviour. She robs him of his gold medallion as a final insult, once the goons and his servants have stripped him of all his belongings. The online coaching session discussed alternative interpretations of the Siren as a wanton courtesan motivated by greed and contempt. Reichlen remains icily indifferent to the Prodigal’s plight.

Ulbricht is harrowing as the humiliated man, every gesture meaningful – the shame of begging and being ignored, ground down by hunger, thirst and his desperation to return home. Just when you think he’s reached his lowest point, Balanchine includes an inessential scene of the goons’ return with the Siren to set up a voyage in a ship with her cloak as the sail. The scene is there to give the Prodigal performer time to be transformed in the wings into a pitiful penitent in a battered cloak, dragging his bruised body back to his family with the aid of a staff. The final moments, to Prokofiev’s reassuring motif, are heart rending as the Prodigal crawls up his father’s body, to be held in his arms like a child. For viewers of the recording, the camera angle deprives Ulbricht of his pathos. In any case, no film can match the Dance in America TV video of Mikhail Baryshnikov as the Prodigal in 1976 – a Russian exile performing the role with Balanchine’s blessing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.