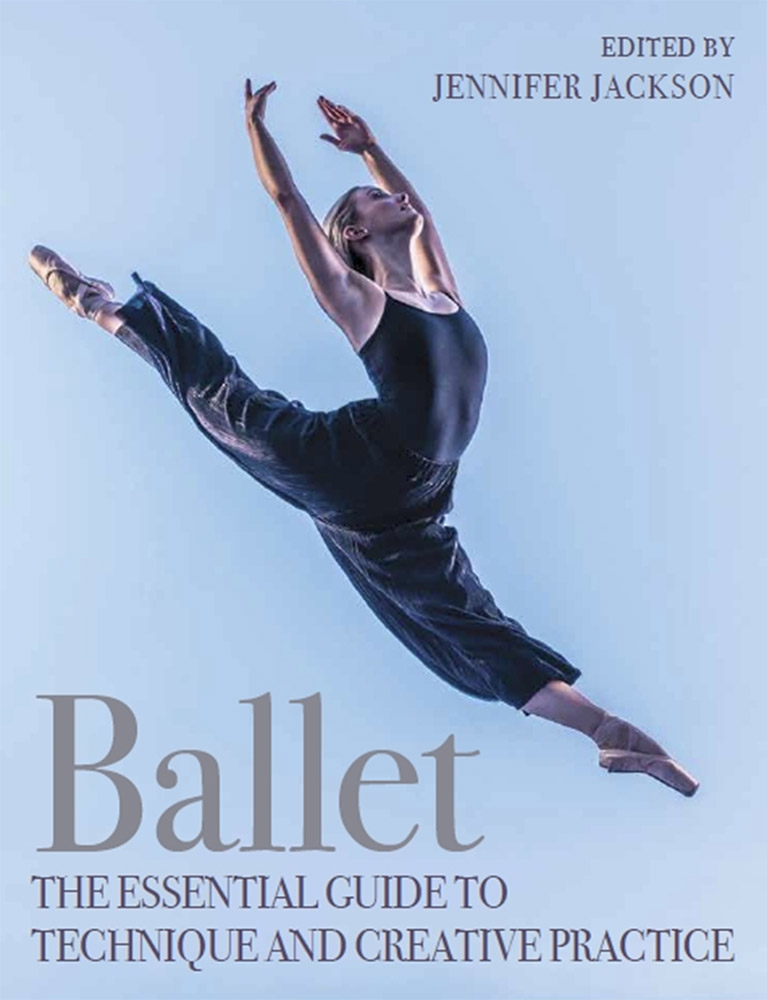

Ballet: The Essential Guide to Technique and Creative Practice

Edited by Jennifer Jackson

The Crowood Press

ISBN 9781785008306, paperback, May 2021, £24

www.crowood.com

Jennifer Jackson made it clear during the digital launch of the ballet guide book she’s edited that it is not a ‘How To’ manual. Dancers need teachers, even if, these days, they are not able to be hands on. Ballet teachers have to use words – technical terms, verbal imagery, anatomical references – not all of which are retained by their students. The intention of this book is to outline the basic principles of classical ballet to those who practise it and who hope to have professional careers as dancers. It can serve as a practical reference aide for students at vocational schools and conservatoires, and for teachers who want to keep abreast of training methods and dance science research.

The first chapters provide background information about the physical bases of ballet technique and the cultural history of its development as a performing art. Historian Anna Meadmore gives a detailed analysis of the different ‘schools’ of ballet – French, Italian, Danish, Russian, American, English – that are often a mystery to students and ballet enthusiasts. As national companies become more and more international, will the distinctions still have so much meaning, one wonders?

The next chapters deal with training: how to lay down the foundation of a sound technique, written by Nicola Katrak, former principal dancer and now teacher at the Royal Ballet School (RBS); what to expect from advanced training between the ages of 16-18 years, written by Mark Annear, head of training at the RBS. These chapters are illustrated with photographs of students demonstrating correct and incorrect placement of the body. There’s lots of practical advice on how to learn and improve, with ‘special tips’ on what to look out for.

The guide book’s aim is to aid senior students ‘to develop their personal best as a dance artist’. This means taking their technical training to another level of physical virtuosity and emotional expressiveness, ‘performing with precision, purpose and understanding.’ In preparation for a professional career, students will perform excerpts from the ballet repertoire, learning to work co-operatively. They might encounter choreographers who want them to be creative, as well as remembering instructions quickly. The expectation here is that advanced students are aspiring to join a ballet company. Advice and insights are offered from successful professional dancers, including Royal Ballet principals Francesca Hayward and William Bracewell.

Only a small minority of vocational students, however, will succeed in becoming company members. The chapter by Karen Berry, entitled Versatility and Creative Thinking, encourages students to gain experience in many different skills, whether or not they hope to become professional ballet dancers. Berry recommends diverse training from early on – jazz, contemporary dance techniques, improvisation, Pilates – rather than specialising in just one technique. Although this is valuable advice for anyone entering the dance ‘industry’, it goes against the grain of earlier chapters that focus on the intricacies of classical ballet training. Elite ballet dancers do need to be versatile to meet the demands of choreographers but, paradoxically, their value for choreographers who come from very different backgrounds is their specialist ability. By the time highly trained ballet dancers have mastered the complexities of their technique, they are equipped to adapt to (almost) any requirements.

In this chapter, as elsewhere, there is an emphasis on self-discovery, on becoming an artist ‘with a unique movement profile’ because every individual is unique in the way they dance. While undoubtedly true, try telling that to the ballet mistress in charge of a corps de ballet! Ms Berry’s advice on adaptability and creativity, complete with learning strategies and improvisation exercises, reads like a manual for contemporary dance students. (There is one already, from the same publisher.) It is helpful guidance, none the less, for enabling a student to become an interpretive artist and possibly a creative choreographer.

A chapter on choreography follows an informative one on Dance Science, written by Stephanie De’Ath and Laura Erwin, staff members of London Studio Centre. It tells students how to avoid injuries as well as deal with them. Exercises are provided, as are photographs of correct posture and alignment and anatomical illustrations. There are recommendations on supplementary training for cardiovascular fitness and muscular strength; advice on mental health, along with coping strategies; nutritional guidance; lists of healthcare resources, books and websites. This chapter provides valuable information for recreational amateurs as well as vocational students and professional dancers.

‘You may be on track for a successful career as a ballet dancer’, writes Jennifer Jackson, who asks: ‘Why study choreography? Can choreography be taught? Are choreographers born, not made?’ Her questions are designed to make a dancer think from the perspective of a choreographer trying to find a creative voice. Ms Jackson has delivered choreographic courses over the years and has interviewed professional choreographers about their practice for the guide book: Ashley Page, Cathy Marston, Andrew McNicol, Morgann Runacre-Temple, Georgie Rose and Aakash Odedra (the only non-ballet-trained choreographer). How and why did they start creating dances? How do they prepare before going into a studio? How does the material develop? How do they collaborate with dancers and the creative team?

The answers are invaluable for would-be choreographers. Promising careers have been cut short by ill-prepared dance-makers losing confidence in the studio, abusing dancers, wasting time and missing deadlines. Further advice on appropriate conduct in a rehearsal studio is given in Deirdre Chapman’s informative chapter towards the end of the book.

But first comes another enlightening chapter, this time on music for ballet, from Jonathan Still, company pianist and music education researcher. A choreographer researching suitable music will need to know about rights and licensing if the work is to be shown in public. If a compilation of pieces by one or several composers is used, who gets the credit and who owns the copyright? In this chapter, Still examines the different meanings of ‘counts’ and beats, meter, timing and tempi. He explains that ‘counts’ used in class and rehearsal tell a dancer when or where things happen but not how or why. At no point does he recommend that a choreographer should be able to read music or that dancers should learn notation – methods of transcribing movement in conjunction with a musical score.

Deirdre Chapman discusses the main systems of dance notation in her chapter on what happens in the rehearsal studio. She assumes that a professionally trained notator (or choreologist) has the responsibility for consulting a recorded movement score of a ballet. A notator at work on a score might be one of many people in the rehearsal room of a large, well-funded company. Ms Chapman provides a list of those likely to be present, with explanations of their duties, including the sometimes-baffling titles of dramaturg, regisseur and repetiteur. A former dancer with different companies, Deirdre Chapman has a wide experience in assisting choreographers and restaging works from the classical and contemporary repertoires. She is well placed to inform anyone curious about the working life involved in mounting a production, new or old, small, mid-size or large-scale. The rehearsal time available will depend on a company’s schedule of performances and repertoire of works.

Dancers have different responsibilities depending on the size of a company: freelancers or members of independent groups need to take on many tasks, as well as managing their own contracts, taxes, travel arrangements and health care. Performers lucky enough to work with choreographers face a range of expectations of their behaviour in the rehearsal studio. They might be required to be creative, collaborative or supportive; they must be prepared to retain, and if necessary discard, material created with and on them. If a work is being restaged, company members must strive to be technically and stylistically accurate in the spirit of the original. Time spent in the rehearsal room pays off in performance on stage.

Like other chapters in the guide book, this one by Ms Chapman deserves a manual to itself. A team of teachers and specialists is required to support a dance student as well as a professional performer. There is a vast amount of information for a practitioner to absorb, practical and theoretical, while engaged in demanding physical exercise. The value of this publication is the possibility of referring back to topics of personal interest, as well as trying out recommended tasks and tips. Helpful overviews from Jennifer Jackson in the introduction and Nicholas Minns in the conclusion remind the performing artist of the essentials of class in the studio. The daily ritual persists for professional dancer and student alike, with the same striving for excellence and love of dancing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.