© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

21st-Century Choreographers: Within the Golden Hour, Optional Family – a divertissement, The Statement, Solo Echo

★★★✰✰

London, Royal Opera House

18 May 2021

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.roh.org.uk

The surprise and pleasure of the musicians in the Royal Opera House (ROH) orchestra pit was evident when Tuesday’s first night audience rose to its feet and applauded the return of live performances, even before the curtains had opened. Koen Kessels, the conductor, acknowledged our cheers with a broad smile (and a new haircut) before launching the orchestra into Ezio Bosso’s music for Within the Golden Hour. Christopher Wheeldon’s playful ballet is full of surprises as it builds from a hesitant start, as if the dancers are gradually coming to life, to a happy ending, the cast of 14 swaying together in silhouette.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

In between come four very different duets and a ‘temple maidens’ quartet of young women sinuously flexing their arms and toros. In the first duet, tall Vadim Muntagirov expertly partners small Anna Rose O’Sullivan (newly promoted to principal dancer with effect from September 2021) as though she was a child pretending to be a grown-up ballroom dancer. Two men, Leo Dixon and David Yudes, compete in macho counterpoint; Valentino Zucchetti manipulates Francesca Hayward in off-balance manoeuvres; Ryoichi Hirano suspends Yasmine Naghdi upside down high above his head before crawling away, frog-like, across the floor. Because the dancers perform Wheeldon’s acrobatic choreography so fluently, the perversity of some of the actions seems unremarkable, disguised by Peter Mumford’s moody lighting.

Next is Kyle Abraham’s 10-minute Optional Family, a divertissement for three dancers: Natalia Osipova, Marcelino Sambé and Stanislaw Wegrzyn on the first night. Abraham, whose work for American companies, including his own, combines classical ballet with a variety of street dance moves, has been commissioned to make a work for the Royal Ballet next year. Optional Family is a stand-alone piece, setting up a dysfunctional marriage in which a co-dependent couple appear to loathe each other. Distorted voices read their letters to each other, listing their grievances over 35 years, possibly exasperated by lockdown: ‘Oh, how I long for the longest distance from you.’

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Osipova and Sambé dance angrily together, in between bouts of her spinning ferociously away from him in a feathery minidress. Computer-generated music by German experimental composer Grischa Lichtenberger has a title, Kamilhan, warning of imminent danger in the home. Sure enough, a good-looking young man emerges, uncomfortable in his own skin as he crawls and beats his feet together. Is he their adolescent son, caught between his possessive parents and determined not to be like them? Or is he Joe Orton’s Mr Sloane, a sexual disrupter of the household? The brief piece ends enigmatically, with Wegrzyn’s head held despairingly in his hands.

After the interval (no drinks or snacks unless ordered in advance, seated at tables) come two works by Crystal Pite. New to the Royal Ballet, both were created for Nederlands Dans Theater; both have been seen before in the UK by visiting companies. The dance theatre idiom of the first one, The Statement, sits uneasily on classically trained bodies, however well executed. The dancers synchronise their emphatic gestures and often cartoonish moves to pre-recorded voices of Canadian actors performing a play by Jonathon Young, Pite’s frequent collaborator.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The dominant prop is a long black table, overhung by a flue-shaped monolith. Around the table are four people dressed in dark business clothes. Two, Ashley Dean and Joseph Sissens, seem to be juniors, taken to task by Kristen McNally, who role is more devious than it first appears. Calvin Richardson is the emissary in a suit from Upstairs, sent to get a statement from the functionaries downstairs. They are required to accept the blame for some unspecified disaster. Objections and obfuscations multiply, on and off the record. The junior pair have a conscience about what happened: they made an existing conflict worse and people died. But they were told by Upstairs to do it and they don’t want to be used as scapegoats.

The dialogue is funny, familiar and sinister, amplified by graphic body language. The table could represent the boardroom of a multinational corporation or the meeting place of governmental cabinet. It’s also a reference to Kurt Jooss’ 1932 ballet, The Green Table, in which grotesque diplomats agree to wage war, regardless of the consequences. In the second phase of Pite’s Statement, Dean and Sissens are dragged along the table, polishing it literally and symbolically with their bodies, before huddling together beneath it as a shelter. Negotiations above them, like the situation they failed to resolve, have escalated out of control.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Not so, it turns out, for McNally takes charge, ensuring that Richardson will be the loser: no more Upstairs for him, as the monolith descends to crush him. The ending is weak, with the cynical assurance that ‘the situation will resolve itself.’ Written in 2016, the spoken dialogue remains evasive: this is a generic boardroom crisis, to be rectified by a statement and a resignation. The piece evades references to real life conflicts and death tolls, arms dealers, profiteers and speculators. We never find out who is going to profit from the cleverly spun ‘statement’.

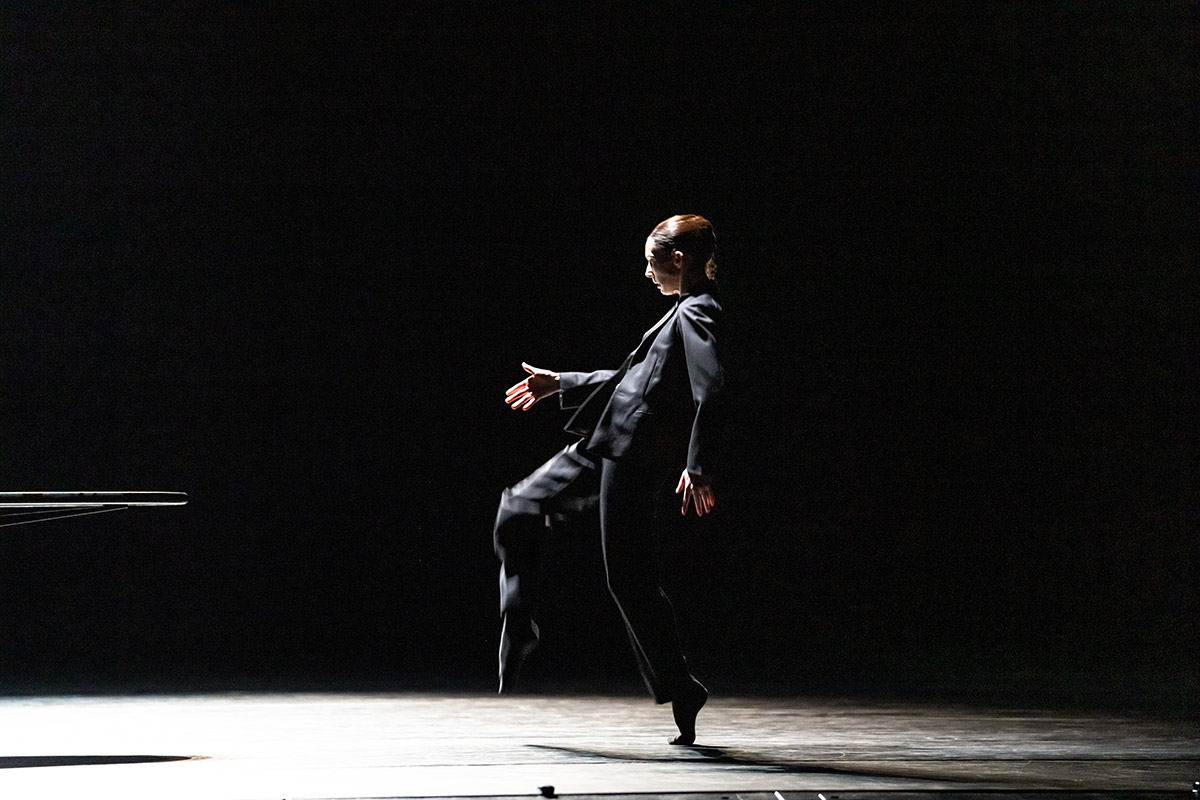

Solo Echo, created in 2012, is essentially a solo for a man (Marcelino Sambé) brooding on his passage through life, surrounded by echoes of his past self along the way to his death. The journey takes place in a wintry snowscape, accompanied by two Brahms sonatas for cello and piano, one early, one late. To the first in E minor, the man suffers the Romantic agonies of adolescence, real or imagined. Like the falling paper snowflakes, the accompanying dancers whirl, slide and pile up on each other. After frantic flurries of action, a slow-motion duet ends with the woman’s departure; another woman slithers in, feet first, and seemingly drags the man into the wings.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

In the second part, to the Adagio Affetuoso from Sonata opus 99, Sambé appears supported by a vertical line of six dancers, all holding each other from behind. He slips from their grasp and is reabsorbed, in a motif of consolation repeated in ingenious configurations. Pite is expert at plaiting and weaving numbers of bodies together, sculpting them into tableaux that then split apart. Inevitably, Sambé is left stranded alone at the end, echoing the dying words in a poem by Mark Sand that inspired Solo Echo.

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

As with Pite’s longer work for the Royal Ballet, Flight Pattern, I find Solo Echo tugs too blatantly at the heart strings, resorting to snow as a metaphor for uplifting transcendence. Although her work is much acclaimed, there’s a sentimentality to her manipulation of multiple bodies as anonymous representatives of mankind. Effective at first, the waves of meaningful motion become monotonous. Solo Echo makes a melancholy conclusion to a programme compromised by Covid concessions: a Wheeldon ballet already recently revived; two Pite pieces made years ago for another company; and a sampler ‘premiere’ from Kyle Abraham. Audience excitement at the start of the evening was replaced by a subdued departure – albeit a grateful one, in the hope of cheerier programmes to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.