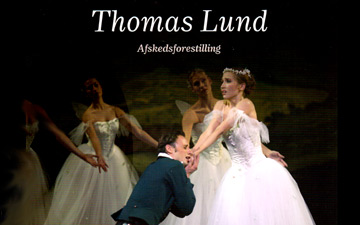

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Danish Ballet

La Bayadère

Copenhagen, Royal Theatre

12 and 14 November 2012

kglteater.dk

Feature on new La Bayadère

Nikolaj Hubbe interview

One of Nikolaj Hübbe’s self-imposed tasks as director of the Royal Danish Ballet appears to be to bring the company’s somewhat eclectic repertoire into better focus, and in particular over the last couple of years he has been re-establishing the Petipa section – not the RDB’s life-blood, of course, but an important, perhaps essential thread even so. Starting with the Swan Lake he inherited – Peter Martins’ almost Petipa-free version – he then commissioned an after-Petipa Sleeping Beauty from Christopher Wheeldon, and finally, in the last act of his own new production of La Bayadère, we get to the real thing: the Kingdom of the Shades. Pure Petipa, the whitest of all his white acts, it allows no room whatsoever for a Danish demi-caractère makeover and nowhere for the dancers to hide. And could they do it? Yes they could.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

It’s been a journey for the company, and for the audience, too. La Bayadère will have been new to many spectators, as it’s never been danced in Copenhagen before, which gives Hübbe much more freedom than when he’s had to challenge so many memories and expectations in his refurbishment of the Bournonville repertoire. His choices, presumably, were to stage either a directly after-Mariinsky production, or Natalia Makarova’s widely-distributed version, or to make one of his own – not a difficult decision, probably, given his limited space and resources, and I think he was entirely right in looking for a new approach that would suit, and be unique to, his company.

So far as I know, no major company has ever before attempted a time-shifted Bayadère, so Hübbe had the whole of history to pick from. He chose the later years of the British Raj – the early 20th century – for various dramatic and decorative reasons, and though I don’t think he’s completely answered the questions that raises, it’s a valid approach and shows the central conflict of the plot from a potentially interesting new angle. (But if you’re British, be warned: there are some cringe-making moments which may make you want to hide under your seat.) Solor and Gamzatti are translated into William and Emma, a British lieutenant and the woman he’s expected to marry – she’s the daughter of the local Viceconsul and has just arrived in India, so her shock when William’s liaison with Nikiya is revealed springs from the difference in race rather than in caste. The other major change is that William, unable to live with his conscience after Nikiya’s death, shoots himself: the Shades scene therefore isn’t his dream, but shows his reunion with Nikiya in some kind of afterlife. And of course that means that there’s no Act 4, no destruction of the temple, which for my part I don’t find much of a loss.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

Choreographically, Hübbe has left the white act untouched, except for the very end where he has to get the principals offstage before a final tableau. Elsewhere the changes in the story have forced some major changes – the British military and their ladies get a number in the engagement scene which Hübbe describes as ‘a nod to Sir Fred’, ribbons and all – and he’s also freely adapted the pas d’action, adding a couple of solos with music borrowed from Paquita, and completely replaced the ‘parrot dance’ with a rather charming number for a dozen small children from the school. But there are still enough landmarks – Nikiya’s solos, the dance of the Blue God (the Gold/Bronze Idol in other productions) – to navigate by. The music is driven along with infectious enthusiasm by the vivacious Estonian conductor, Anu Tali – the only thing I wished was that she and the dancers could come to some agreement about the timing of the last flourish in several of the solos.

Richard Hudson, who also designed this season’s Golden Cockerel for the company, has created a very simple permanent set but let himself go with the costumes: rich, vibrant colours for the Indians, a much more restrained palette for the British. And there’s an elephant as well as the mandatory dead tiger. Anders Poll’s imaginative lighting creates depth and perspective on the relatively small stage of the Royal Theatre – I’m so glad they chose to use this theatre rather than the new Opera House – and beauty and atmosphere as well, especially in the blue, drifting light of the Shades scene.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

Hübbe put on three almost completely different casts for this short run – which continues later in the season – and although I understand the importance of getting as many as possible of his dancers on stage, in the two performances I saw there were some who looked stretched to the very edge of their capabilities, and even beyond. Out-and-out virtuosity is not, in any case, a hallmark of this company, and it was in the show-off dancing that a certain falling-short was most apparent. On the other hand there were some very pleasant surprises: Eliaba D’Abadia as the Blue God gave much the best performance I can remember seeing from him, and in one of the interpolated solos Holly Jean Dorger was quite simply a delight – it’s lovely to see someone dancing with such serene confidence and with such an air of enjoying the choreography and wanting to share her pleasure with the audience.

From the RDB, of course, one expects some excellent performances in the character roles. Luxury casting gave us Mads Blangstrup as the Brahmin, dominating the stage with his arrogant swagger; his alternate, Fernando Mora, had his own, quieter authority. Morton Eggert lifted the role of the leading fakir from a bit-part to a major player, though I hope he’ll hold it just as it is and not fall over into parody; and Poul-Erik Hesselkilde impressed me by the less-is-more economy of his acting as the major-domo.

I saw Camilla Ruellykke Holst and Amy Watson as Emma/Gamzatti, a fascinating contrast to each other in all sorts of ways. Holst, at her first appearance, looked the perfect, carefully-brought-up and rather naïve English girl, a bit unsure of herself in this new environment but quickly finding her feet – and her temper – in her confrontation with Nikiya; Watson was perhaps a rather older young woman, very conscious of her status and looking for trouble from the start and I really enjoyed her acting. She can do fouettés, too, but neither she nor Holst showed enough confidence and polish to convince in the pas d’action.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

According to Hübbe’s co-producer, the Bolshoi-trained Eva Draw, these early performances show a work in progress, with the dancers learning and growing as the run proceeds. That’s especially the case, perhaps, with the men dancing Solor: it’s a much longer and more demanding role than they are used to and both Marcin Kupinski and Ulrik Birkkjær looked close to exhaustion by the time they reached the Kingdom of the Shades. In the earlier scenes Kupinski was the more sincere and aware, Birkkjær the more flirtatious, relying on his charm to get him out of trouble; both of them really made something of the suicide scene, giving it an adult and quite moving sense of regret, guilt and quiet despair.

The performance I’d been most looking forward to was Gudrun Bojesen’s debut as Nikiya – the role seems such a perfect fit for her gifts that it’s hard to understand why she’s never been invited to do it before. Her very first solo was so good that I’d have gone home happy even if she’d done nothing else: she was Nikiya, living and breathing, danced and acted at the very highest level, the equal of the very greatest I’ve seen. I loved, too, the way she did the solo that leads up to her death, making the fast section at the end – which often seems awkwardly incongruous – into an expression of desperation and fear. She and Kupinski made the beginning of the Shades scene into a continuation of their story – he was lost and bewildered, she didn’t understand at first what had happened, and then only gradually came to offer him forgiveness. I’d guess she will relax into some of the technical passages as the run progresses, but already it’s an immensely satisfying and moving performance. Gitte Lindstrøm, whose first Nikiya marked her return to leading roles after a long absence, achieved a success of her own by a very different route: her bayadère is a stronger character, perhaps, and certainly more openly sexual; her dancing, though less nuanced than Bojesen’s, is strong and clear and unfussy and very pleasing.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

And then there was the corps de ballet, 24 of them coming down the famous ramp for perhaps the most testing few minutes in the whole repertoire. They can be proud of themselves, especially the six in the front row: I’ve no doubt the Mariinsky and the Paris Opera Ballet do it with more fluency and flow – but then they’ve had an awful lot more practice, and there are a lot more of them too. (A spate of injuries meant that at the second performance I saw the 24 were reduced to 22, even with the soloists due to dance the three leading shades taken back into the corps and replaced by principals.) Eva Draw must be proud of them too, and the audience loved them: both nights the applause lasted right through the beginning of the music for the next section.

So La Bayadère lived, even in its new setting and without quite a lot of its choreography; and if the way the seats began to sell during the run is any indication, it’s going to be a popular addition to the repertory. But that’s enough, perhaps: I hope that if Hübbe comes in one morning all bright-eyed and says he’s got this great idea for a Raymonda updated to 1914, someone in authority will just kindly but firmly say ‘No’.

You must be logged in to post a comment.