© Angela Sterling. (Click image for larger version)

Doug Fullington at PNB

Several weeks ago, before the première of Alexei Ratmansky’s new Sleeping Beauty for American Ballet Theatre, I had a long chat with Doug Fullington, who assisted Ratmansky on another recent ballet reconstruction, that of Petipa’s Paquita for the Bavarian State Ballet. Fullington, who runs the audience education programming at Pacific Northwest ballet, has a longstanding interest in ballet notation, which he taught himself to read when he was in college. He has written widely on the subject and has been involved in various reconstructions, including a Giselle based on primary sources for Pacific Northwest Ballet, Pierre Lacotte’s reconstruction of The Daughter of Pharaoh for the Bolshoi, a Le Corsaire for the Bavarian State Ballet and various stagings for the Pacific Northwest Ballet School.

Fullington and I talked about the recent renewal of interest in the use of nineteenth and early twentieth-century notations in ballet reconstructions. This is an edited version of our conversation.

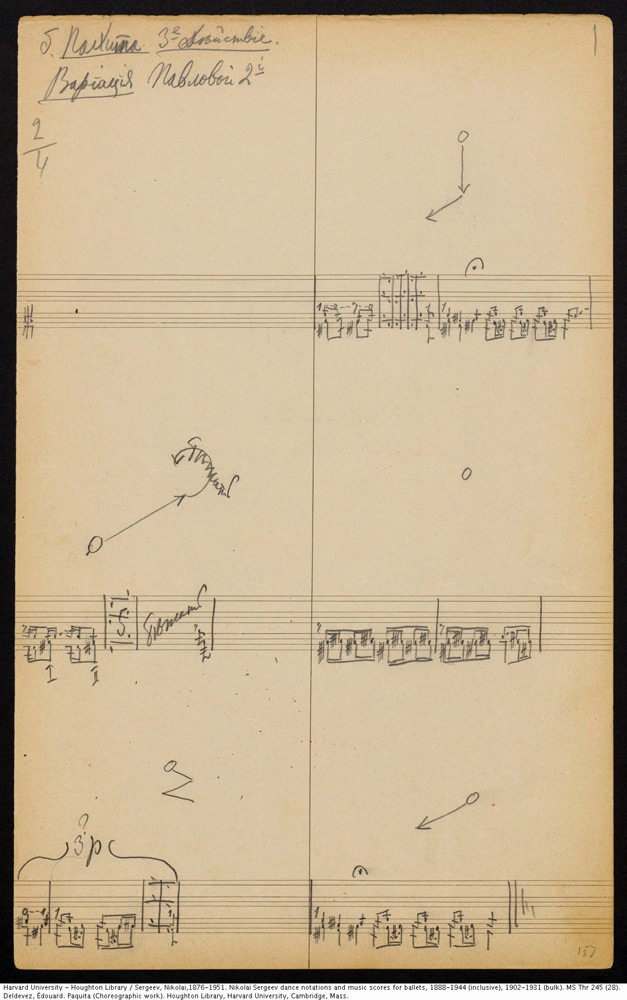

A page of Stepanov notation for the Paquita Grand Pas. © Image courtesy Doug Fullington.

How did you develop your interest in Stepanov notation?

I was given Roland John Wiley’s book on Tchaikovsky’s ballets when I was 17. My background was in music, and I’d always liked ballet music. When I read about the notations, I thought: “This is a way I can be more involved in ballet.” Then I got Wiley’s translation of Alexander Gorsky’s essays on Stepanov notation. Gorsky produced a more complete key to the notations than Stepanov’s original. Later, I took ballet classes and played for class at Pacific Northwest Ballet School.

Do you have a sense of why Vladimir Ivanovich Stepanov (1866-1896) created his system?

He was young and in the corps and had an interest in anatomy. I don’t know his motivation, but I believe it was the first time anyone in the St. Petersburg theatre had done it. Interest was limited, but a few key people, including Petipa, initially approved. It eventually seems to have annoyed Petipa, because others, like Alexander Gorsky, then had the means to go off and stage his works. Learning the notation gave these people a leg up; it gave Nicholas Sergeyev a career outside of Russia.

How many ballets were preserved in Stepanov notation?

There are 24 ballets and 24 opera ballets in the Sergeyev Collection at Harvard. We know some notations have not survived. I don’t think anything has turned up in Russia beyond the two Gorsky pamphlets.

How clear are the scores?

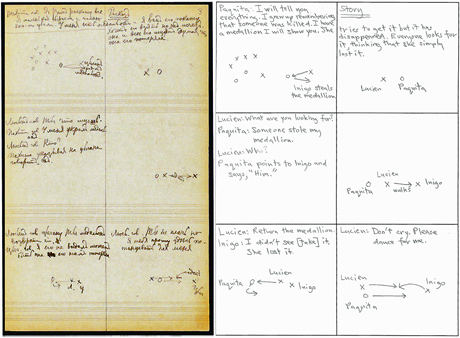

The earlier notations were works of art. They were very precise, down to the position of the torso, head, and wrist, essentially from start to finish. Then you get more standard examples on portrait-oriented paper. Most ballets were notated by more than one person, and not necessarily at the same time. And these are less complete. Sometimes only the legs and feet, or the ground plan, are given. Reconstruction using these notations is necessarily interpretative, so you’re going to have a lot of differences. 99.9% of the time you don’t have all the notation you need.

A page of Stepanov notation (left) and Doug Fullington’s translation (right). It’s part of the action/mime from Paquita Act I. © Images courtesy Doug Fullington.

Are there multiple versions of dances in a single ballet?

Sometimes, yes. For example, in Sleeping Beauty, the notation for the Lilac Fairy variation was done twice. One is a record of the version danced by Marie Petipa; the other is more difficult.

Based on your conversations with Alexei Ratmansky, how closely did he hew to the notations in the Paquita you collaborated on, and in his new Sleeping Beauty?

Alexei wanted to follow the notation as literally as possible: the extension of the leg, the position of the feet, the degree the leg is bent. For Beauty, there are also very elaborate drawings by Pavel Gerdt [the first dancer to perform the role of Prince Désiré], which Alexei used as a principal source for the third act pas de deux.

You worked with Pierre Lacotte on his reconstruction of The Pharaoh’s Daughter for the Bolshoi in 2000. How much of the notated choreography did Lacotte end up using?

I set the steps on dancers here in Seattle and sent him the videos. He didn’t like them at all. He essentially said: “These can’t be Petipa.” He used bits and pieces, but he felt most of it was too old-fashioned. For many people, the notated dances contradict and peel back too many layers of our ideas about how we should hold our arms and legs and seems to reverse certain advancements in pointe-work. We have this idea that the changes to this repertory have all been improvements.

What impression have Ratmansky’s re-imagined Paquita and Sleeping Beauty left you with?

I feel they demonstrate that these ballets were a much broader form of entertainment, full of character dance, pantomime, children, and plenty of comedy and wit. There is a great sense of spontaneity. And there is a more evident influence of French technique, and neo-Baroque dance.

A page of Stepanov notation (with some translation and notes) of Le jardin animé – Le Corsaire. © Image courtesy Doug Fullington.

Why do you think these sorts of efforts haven’t been undertaken more frequently?

I think directors may feel like it’s a risk to do something old, that it will be boring or suggest they are presenting old-fashioned repertory.

What are you working on now?

We’re rehearsing selections of Le Corsaire based on Stepanov notation for Pacific Northwest Ballet School.

You can read more about Ratmansky’s staging of The Sleeping Beauty for ABT in this article for Dance Magazine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.