© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

Rambert

Life is a Dream

★★★✰✰

London, Sadler’s Wells

23 May 2018

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.rambert.org.uk

Kim Brandstrup’s new evening-length work for Rambert is, in part, a meditation on the nature of creativity. At its heart is a theatre director who presides over a rehearsal of a play. In his fitful dreams, the performers and their roles intermingle until he no longer knows what is real and what he has imagined. He could be Brandstrup himself or Rambert’s recently departed artistic director, Mark Baldwin; or an avant-garde Polish theatre director resisting Soviet cultural control.

Brandstrup keeps so many options open that the narrative thread of Life is a Dream is hard to pin down, even if you have read the programme notes and mugged up the 1635 play of the same name. Pedro Calderon de la Barca set his allegorical Spanish play in Poland, recounting the tale of a prince, Segismundo, who has been incarcerated by his father since childhood. He knows nothing of the outside world until a woman, Rosaura, dressed as a man, effects his rescue. He goes on a rampage of excess until, drugged into sleep, he is imprisoned once again. He is told that everything he experienced was only a dream.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

When he is let out a second time, he has learnt his lesson. What that lesson is depends on how Calderon’s play and Brandstrup’s dance drama can be interpreted. In the end, the dreamer has to come to terms with himself and his frustrated expectations.

When the dance piece starts, where are we? In a derelict rehearsal space (possibly in Poland in the 1950s or 1960s). It has two enormous windows in its back wall and a single door, stage left. A man the synopsis tells us is the director of a play (Liam Francis) is dozing at his desk. He is also Calderon’s sleeping prince, Segismundo. Members of the cast materialise in the dusky shadows, some in casual clothes, others in versions of 17th century costumes. The only props are a bedframe and an old-fashioned tailor’s dummy. (Designs by the Quay Brothers, costumes by Holly Wadddington.)

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

When a dark-haired woman, Nancy Nerantzi, enters to rehearse playfully with the bed as her partner, the music changes from quiet, rather sinister strings to a popular dance tune on the radio. Both kinds of music are by Witold Lutoslawski, the Polish composer who survived Nazi occupation and Soviet socialism. (He died in 1994). Brandstrup, introduced to Lutoslawski’s music by the Polska Music programme, found it suited his dramatic needs perfectly. Rambert’s orchestra, conducted by Paul Hoskins, with Charles Mutter as the violin soloist, makes the case for Lutoslawski as a composer for dance, bringing him to the attention of audiences unfamiliar with his work.

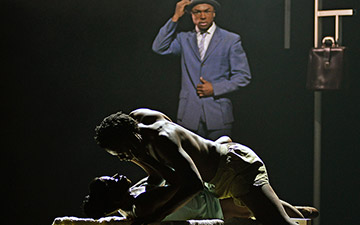

Nerantzi is one of several dancers portraying Rosaura, Segismundo’s rescuer. Each of the main characters has at least three interpreters. Rosaura is associated with videos projected behind the windows, giving tantalising glimpses of the natural world: leaves, clouds, water, a murmuration of starlings. Francis, as the director, seems a Prospero figure, able to magic up these visions, as well as to manipulate his cast, as he does the tailor’s dummy. He has an avatar as the prince, Miguel Altunaga, who is eager to discover everything of which he has been deprived, including the touch of a woman.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

Brandstrup emphasises the importance of touch by having the characters’ hands covered by long sleeves until they are pushed up to free the fingers. Touch is a guarantor of reality. It is also the way a choreographer communicates and dancers connect physically with each other. Brandstrup’s movement language is balletically graceful and athletically powerful, with high-flying lifts. One of the Segismundos goes too far in his duet with a Rosaura, assaulting her as she fights back, putting his hand on her breast. Excitable strings imply that he is out of control, rampaging for freedom or anarchy.

Red-headed Edit Domoszlai now appears to be the prince, recaptured as a prisoner in a straitjacket on the bed, a place of asylum. This is her ‘Anastasia’ moment from Act III of MacMillan’s ballet, seeking reality by finding her fingers and feeling her feet on the floor. A big black X is projected onto the black wall. Her rebellion against being confined is amplified by other members of the cast until she joins them in sitting together, facing the windows. In a coup de théatre at the end of Act I, the wall falls away as the moon rolls across the night sky.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

Where are we in Act II? The synopsis says that the director ventures outside the boundaries of his room to conquer the world. The stage area is bare, apart from some remaining pillars and the backs of scenery flats – and the bed and dummy. Elements of action from the first half are reprised, including Nerantzi’s reappearance as the prince’s would-be rescuer or potential lover. The director (or his avatar) manoeuvres a Klieg light around the dark space, spotlighting the performers as if for a black-and-white film. He is caught in the glare himself, unable to escape scrutiny. The twin leading figures, Francis and Altunaga in modern day clothing, then mirror each other in a challenging duet: their duel could be alter-egos confronting each other or Segismundo in Calderon’s play, seeing himself for the first time in a looking glass. Is this reality instead of illusion?

I have no idea, after a first viewing, what conclusion is reached. I would guess that the director/choreographer doesn’t conquer the world. Or that the woman of his dreams isn’t attainable. Or that imagination and creativity are more enticing than coming to terms with his limitations. Whatever is described in the synopsis and programme notes is not discernable on stage, which may serve Brandstrup’s liking for ambiguity but thwarts viewers’ hopes of an intelligible narrative. It is hard to identify the dancers in their multiple roles and even harder to empathise with their characters’ dilemmas.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

The staging is gorgeous (if sepulchral), lit by Jean Kalman as if illuminated by hallucinations. Silvery surfaces blur reflected images; costumes are coated with patinas, their shapes taken from X-rays of 17th century garments and their underpinnings. Brandstrup and his team of designers have created a fantasy world within a stark theatrical setting; the second half comes as a let down, as perhaps it did to Segismundo, when, chastened, he was finally freed. Can any creator, any director, any performer, ever be completely satisfied?

You must be logged in to post a comment.