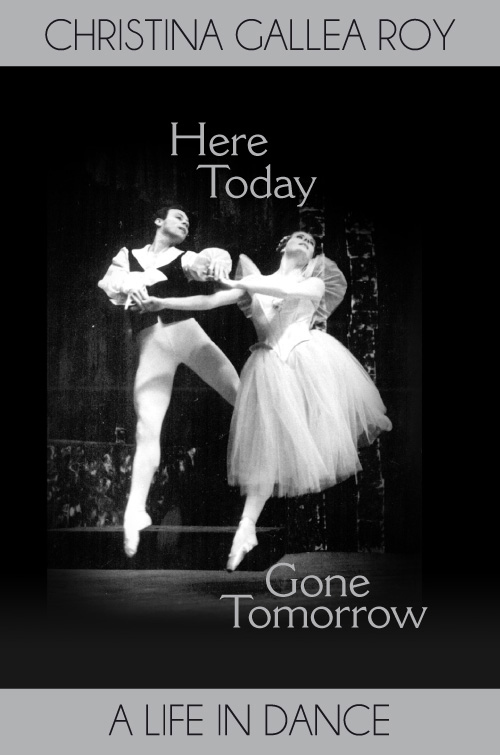

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow

By Christina Gallea Roy

Book Guild Publishing, Hardback

2012, 338 pages, illus., £17.99

www.gallearoy.com

Publishers page

Amazon link

It would be easy to pick this book up, glance at the blurb and put it down again unread: a long and detailed history of a small and long-defunct company run by someone you may never have heard of, it’s certainly rather lacking in instant ‘must have’ appeal. Discarding it would be a mistake, though – a big one, if you’re at all interested in ballet’s recent history. This is a fascinating story and I’d go so far as to call it an important one. There are plenty of accounts of the rise of big, famous companies, but very few of those at the opposite end of the business: this one gives us a picture of the ballet world away from the great opera houses, and of the struggle to survive out there. It could also be read as a case study for anyone thinking of setting up a new company today – some of the circumstances may have changed but the problems and challenges still sound very familiar.

Christina Gallea arrived in London from Australia on her 17th birthday, hoping to make a career for herself as a dancer. After a year spent studying with Audrey de Vos and stints with the Frankfurt Ballet and the Ballet der Lage Landen in Amsterdam, she joined American Festival Ballet – a touring company working mainly in Europe – and there she met the young German dancer Alexander Roy. They formed a partnership both on and offstage and after working with several different companies, and getting married, their thirst for independence led them to put together a recital programme of solos and pas de deux and strike out on their own. Over the next three decades their two-person enterprise expanded into an established company with a huge repertory, mainly choreographed by Roy himself, touring all over Europe as well as in the Far East and both North and South America.

Gallea relates the growth, and eventual decline, of the company – known originally as International Ballet Caravan and later as Alexander Roy Ballet Theatre – with an amazing amount of detail, drawn from her own diaries and from an extensive archive of photographs, press cuttings and publicity material. The early days, when the two dancers travelled Europe in an old Volkswagen Beetle with all their costumes and sound equipment in the back, are the most fun to read about and perhaps are some of Gallea’s happiest memories: they were living almost literally hand-to-mouth but they were young, happy in their independence – always of the highest importance to them – and their tours took them to some very pleasant locations. Every spa town and resort in the south of France, every small town in Germany, had its own theatre, more or less well-kitted out technically and apparently happy to engage a completely unknown company and what’s more to invite them back, even to the town where their first appearance only enticed an audience of 28. So it’s perhaps not surprising that they were turned down when they once applied for an Arts Council grant: the assessor, rightly, spotted that they were keener on their summer tours in Europe than they were on doing outreach work as an English regional company. (Though they did later get money from the Arts Council for specific new works, and did a considerable amount of outreach work on their own account.)

By the mid-1970s the company was dancing well over a hundred performances a year; it had a permanent London home, a core of seven dancers (with more taken on for major engagements), and a wide repertory of short ballets – mostly dramatic and still mostly by Roy – as well as abbreviated versions of Coppélia and other classics. But opportunities in Europe began to dry up: the spa theatres closed or chose to feature lighter entertainment, and touring in the UK was becoming prohibitively expensive, badly hit by the terrifying inflation rates of that time. Forced to look further afield, Gallea and Roy set up their first long-distance tour, a two-month visit to south east Asia – a success and also something of a rite of passage, introducing them to a whole new set of problems: work permits, dubious travel agents – they had to pay for the whole group’s air fares in cash, handed over in a pub off Tottenham Court Road – and the shock of extreme climates and culture clashes along with the inevitable jet-lag and general exhaustion.

More tours followed, more elaborate work was created – a full-length Beauty and the Beast, a two-act Midsummer Night’s Dream, even an Alice. All this time Gallea had been dancing as well as directing the company and doing the lighting and every other possible job when required, but by the middle of the 1990s she had retired from performance and both she and her husband began to find the stress of keeping the company going was getting too much for them. Competition from eastern European touring companies was growing and in the lifetime of their company they had also seen the modern dance world explode from almost nothing, and so in 1999 the Alexander Roy Ballet Theatre finally closed down. The book winds down in parallel – the later stages begin to feel a little repetitive and I guess that’s what the actual experience felt like too.

The overwhelming impression I take from the book is of the constant unrelenting hard work it took to keep a small, independent company on the road for so long. So many ballets to create, so many costumes to be designed and made and washed and washed and replaced, so much fund-raising and publicity work and book-keeping and hiring and replacing of dancers – but Gallea spells out on the last page that she and her husband see themselves as ‘fortunate and privileged’ to have spent their lives in their chosen profession – ‘something one could not call ‘work”. I assume the book is self-published but it is very far from being a vanity project: more people with stories like this to tell to a specialised audience could use the same process to the benefit of us all.

You must be logged in to post a comment.