© Francette Levieux. (Click image for larger version)

The Nureyev Collection

Centre national du costume de scène et de la scénographie

Moulins, France

18 October 2013

www.cncs.fr

www.nureyev.org

www.rudolfnureyevdancefoundation.org

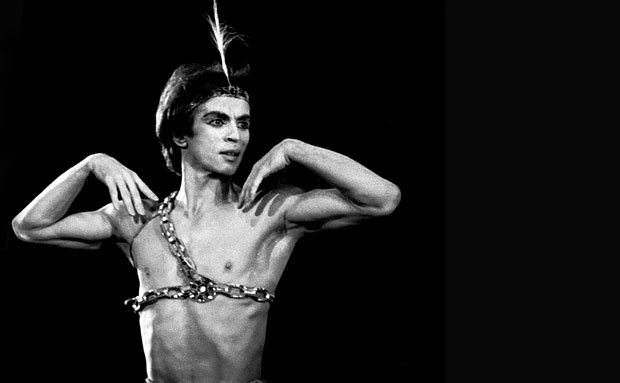

A small town in the Auvergne in France seems an unlikely setting for the flamboyance of Rudolf Nureyev but Moulins is home to the Centre national du costume de scène (CNCS). With typical French flair, CNCS’ first permanent display presents more than Nureyev’s stage costumes.

Ezio Frigerio – who designed many of Nureyev’s productions as well as the mosaic kilim that shrouds his grave at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois on the southern fringes of Paris – has created a theatrical setting that honours a legendary name in dance and portrays Nureyev’s incredible appetite for life.

© Paul Arrowsmith. (Click image for larger version)

“Rudi’s taste was phenomenal,” recalls his contemporary at The Royal Ballet, David Drew, who appeared as Wilfred to Nureyev’s Albrecht in Giselle, the occasion of the Russian’s celebrated Covent Garden debut in 1962, glimpsed on film here. Drew remembers, “The whole company would be invited to his house near Richmond Park. It was exquisitely decorated. There were kilim rugs, medieval artworks, icons. It is easy to dismiss as simply a rich man’s indulgences but it wasn’t just thrown together. Rudi had the most wonderful, innate taste.”

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

Drew also recalls being driven into the hills above Monte Carlo following a performance. “The air was thick with fireflies, on the roads where To Catch a Thief was filmed. We arrived at a villa, stupendous. And here was another collection – his own, not organised by an interior designer. This was Rudi. He travelled all round the world, a magpie, hungry for what he had been denied in the communist world.”

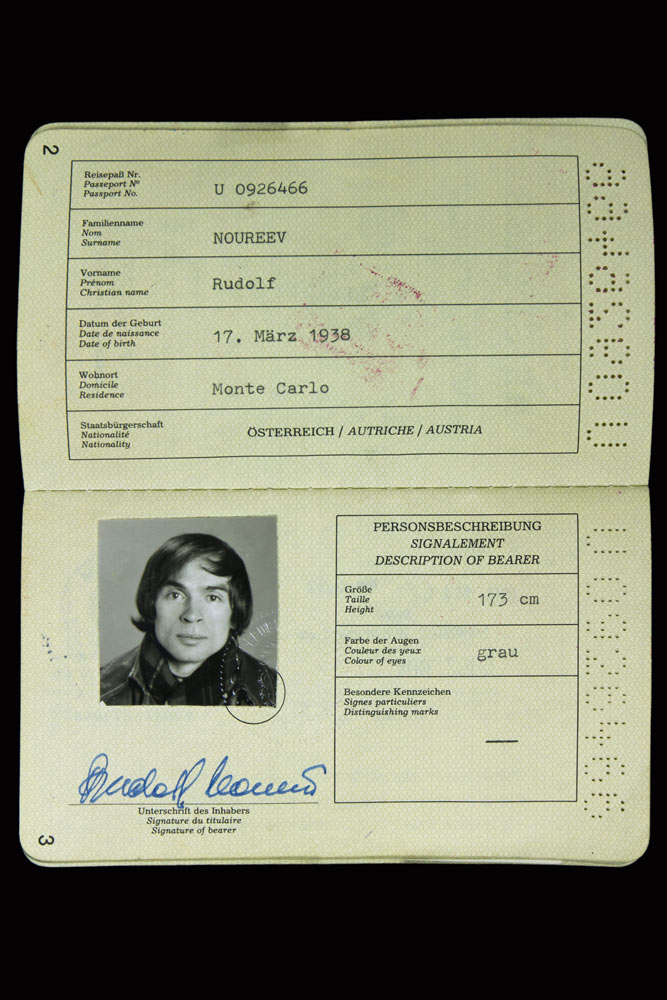

The Moulins exhibition presents evocative family photos, redolent of Soviet Russia, showing just how far Nureyev travelled. We see him as an 18-month old, in his nappy, with mother Farida and sisters Razida, Lilya and Rosa. His father Hamet is stiff in army uniform, “on the western front,” in 1943. From the end of his life, Nureyev’s address book reveals contacts for Arnold Schwarzenegger, Liza Minelli, Andy Warhol, Yves Saint Laurent …

© André Chino. (Click image for larger version)

CNCS is housed in what were military barracks from the 1700s. Reopened in 2006, its remit is as a conservation centre for the Opéra national de Paris and Comédie-Française. Temporary exhibitions have featured Jean Paul Gaultier and Christian Lacroix’s theatre work, the Ballets Russes’ early forays into opera and – betwixt the sublime and ridiculous – costumes for operatic divas and the circus.

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

Now, a red Aids awareness ribbon circles the honey-coloured stone building. It bears Nureyev’s contention, “As long as I dance, I remain alive.” That provides the rationale – and challenge – for the collection. Can a static exhibition capture the vitality of Nureyev’s force of personality and wanderlust?

Claude Blum, president of the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation was sceptical. Speaking at the inauguration, a latter day gathering of around 150 of Nureyev’s friends, Blum said, “Would Nureyev ever have found his way here?” In 1975 the dancer created a foundation to support his family in the Soviet Union and to help dancers, ballet schools and companies there. “Dealing with the family was not easy,” admits Blum. More straightforward were the philanthropic grants and scholarships.

© Paul Arrowsmith. (Click image for larger version)

The foundation established filmed archives in New York and Paris, commissioned a biography by Julie Kavanagh and created websites cataloguing Nureyev’s performing career and dancers’ medical concerns. Which left the question, how to comply with Nureyev’s wish, expressed in his will, for a ‘lieu de memoire’ – a memorial space?” For that purpose, the foundation retained several hundred objects collected by Nureyev, rather than auctioning them, as the majority of his estate was.

For Blum, the CNCS’ display spaces, carved out of stables and barrack rooms, did not appear viable. In 2009 an exhibition there, featuring Nureyev’s stage costumes, furnished with important loans from the Royal Opera House and Paris Opera Ballet, revealed the potential of what could be achieved. “I was won over,” concedes Blum.

© Francette Levieux. (Click image for larger version)

Occupying a frankly awkward and claustrophobic space the exhibition is small but impeccably calculated to create maximum sense of Nureyev the behemoth. The investment for Moulins is considerable, the cue to attract greater visitor numbers. For anybody planning to visit, unusually but helpfully CNCS is open daily and continuously – without the archaic French habit of closing for lunch. Blum’s foundation and CNCS have spent nearly 100,000 euros to display the collection, with almost a further 500,000 euros provided by the Ministry of Culture’s support scheme for regional museums in France.

Visitors are immediately plunged into inky gloom, a backstage corridor of indigo blue drapes, drawn from the proscenium curtain of the Paris Garnier. As though captured in a follow spot on stage, costumes worn by Nureyev the dancer shine from the darkness. The first, a simple pale blue cotton doublet, is a recent acquisition by CNCS and insignificant other than it was worn by Nureyev soon after his defection, on tour with Erik Bruhn and Rosella Hightower.

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

More typical is the lavish green velvet tunic for Romeo and Juliet from 1977, designed by Franca Squarciapino for London Festival Ballet. The ornately crafted silvery appliqué reads far more impressively under display conditions than in the theatre. Nicholas Georgiadis is represented by Don Quixote and Raymonda, both fantasies in lamé, braiding and appliqué applied to the highly tapered and fitted doublet that Nureyev preferred. The craftsmanship involved is pure couture.

Martin Kamer, who worked with Georgiadis and Barry Kay, remembers, “Nureyev would always want changes to costumes, but, which made, would demand, ‘Why change?’ Rudi always discussed his ideas drawn from literature, painting, sculpture and history with his designers.” Typical of Nureyev’s eclectic but informed taste, his collection included prints from the 1700s illustrating Don Quixote.

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

Nureyev the choreographer is depicted by his 1930s Hollywood Cinderella, his 1986 production of Cendrillon in Paris. An outfit for Sylvie Guillem by Hanae Mori is pure Ginger Rogers, gold sequinned jacket, flowing calf length skirt, quizzically feathered hat and transparent shoes dotted with tiny sparkling lights. From La Bayadère, three costumes by Squarciapino reveal the blurring of Nureyev’s personal taste for opulent textiles and oriental costumes and his design aesthetic for the stage. Fantasy and reality meet in a tunic for Nikolai Tsiskaridze as Solor, fashioned from Indian emerald green silk, embroidered and patterned in gold thread, sumptuously luxuriant. To see such quality applied to a stage costume makes Nureyev’s claim, “I live to dance, I live only because I dance,” at once comprehensible.

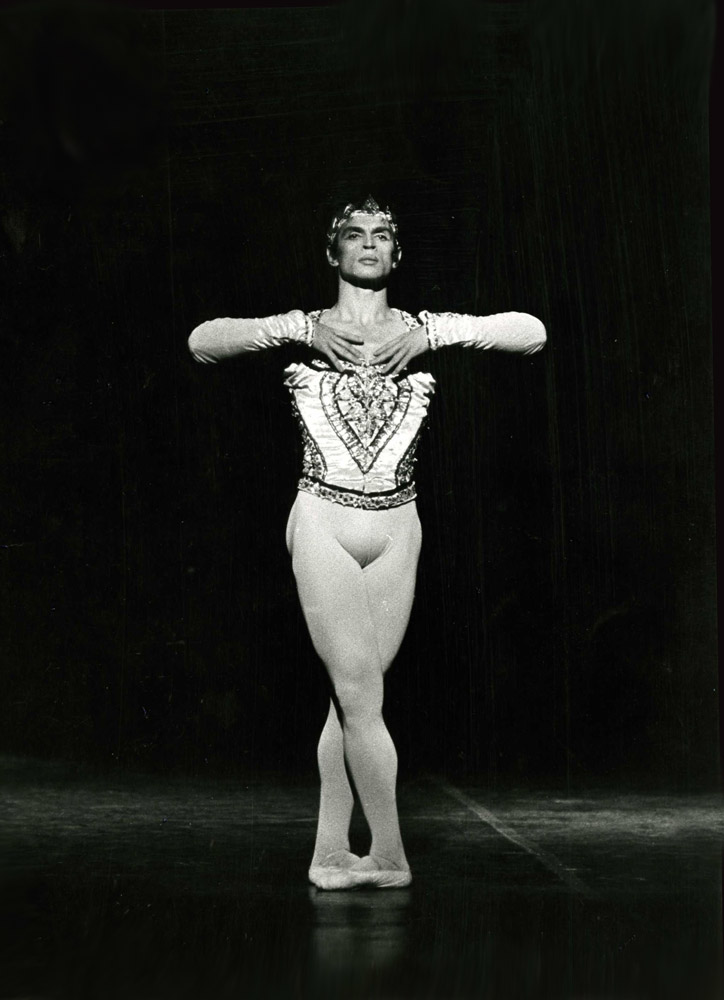

A timeline reminds us of the many facets of Nureyev’s insatiability. By 1961 in Leningrad, Nureyev glowers at the camera, already a moody rebel. A photo of the Kirov’s Nutcracker, where he partners Alla Sizova, is typical of the artistic paucity of Soviet productions compared to the theatrical zest Nureyev later brought to his own stagings. By 1983, Nureyev is triumphantly posed on the roof of the Paris Garnier, when appointed director there, a literal high point.

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

Nureyev’s unwillingness to leave the stage is tactfully suggested. From 1991, he is a maestro in white tie and tails. The cities where he conducted were scarcely top flight – nor were the venues in which he danced during his last decade. From a Lumière magazine cover published in 1977 Nureyev smoulders in Ken Russell’s Valentino, a film the even director said he would rather forget. Nureyev’s sorties away from ballet as his physical powers declined – indeed most of his later dance performances – are better forgotten, but this image captures his still charismatic potency.

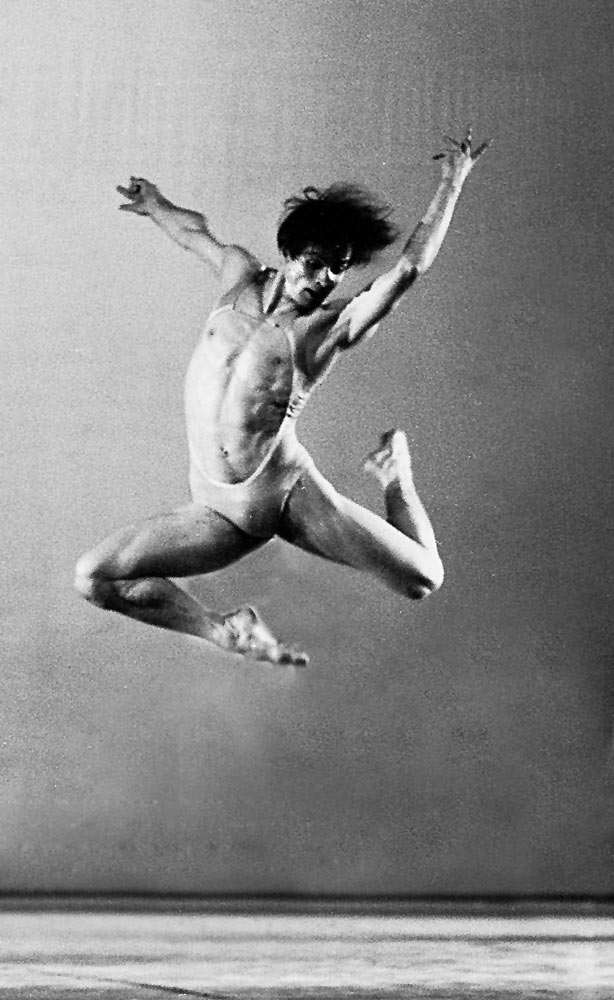

“Rudi always danced large to make the stage look small and his own dancing bigger. He was not above that level of showmanship,” describes David Drew. “He always went for broke – a mixture of heart and mind. He ran the gamut, from one extreme to another. Nothing was halfway for him, which is why he could be a right bastard. But weirdly he was not big headed. He knew when he was not good enough.”

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

At the time of his death Nureyev had seven homes. Besides the villa above Monte Carlo and the London house there was an apartment in the Dakota building, New York, a ranch in Virginia, homes on Saint Barthélemy’s in the Caribbean and off Italy on the Galli islands. For an inveterate traveller, his Paris apartment was as much home as anywhere. There Emilio Carcano, a designer and decorator trained by Lila de Noboli, created opulent theatrical settings for Nureyev’s art and antiques. Recreated for the exhibition, embossed, Cordoba-style leather wallpapers are the backdrop for Nureyev’s penchant for male nudes, painted or sculpted or real.

Nureyev’s jewellery is an exercise in machismo – chunky, engraved or embossed antique silver chains, bracelets and belts. A collection of peaked leather caps and tartar headgear hang from a hat stand. A golden Japanese kimono and embroidered Chinese coat are the ultimate apparel for self indulgence.

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

The exhibition’s small cinema corner is not sufficient for the demand – still – to see Nureyev dance. Unusually for filmed ballet performances, believes Drew, “Rudi does translate to film,” yet familiar footage, screened here, is not wholly flattering. A 1977 film of Marguerite and Armand obviously edits together different takes, the impulsive whirl of Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn’s performances stifled. It is Nureyev’s observation in a filmed interview that leaps out, “The prince must always be as important as the ballerina.”

For conservation reasons, exhibits will be rotated. One costume owned by the CNCS not currently exhibited is the velvet cloak lined in silk designed by James Bailey worn by Nureyev for his Covent Garden debut. That performance established his celebrity status before the term became meaningless. Drew describes, “He went to great lengths with the draping of his cloak in Giselle. He was fastidious. The way he made his entrance, carrying the lilies for the grave was all very studied and practised. That attention to detail was part of his Russian training.”

© CNCS / Photo Pascal Francois. (Click image for larger version)

From the same period, a gold lamé jacket from Carnaby Street places Nureyev in the vanguard of everything hip. But a small travel bag – sufficient for the fewest personal effects, from Nureyev’s last UK tour in 1991 – is witness to his discipline and constant need to work. Compare that to the travel trunk – or coffin – suggested beneath the sculpted folds of his grave. The exhibition has Frigerio’s model but an actual sized photographic wall of the grave, with the cemetery’s silver birch trees and Russian Orthodox crosses, is a sobering endpoint. “Rudi embraced totally the freedom of the west but he felt dislocated from Russia. Genuinely his heart was there,” believes Drew.

Nureyev’s impact has been told many times. As Drew saw it, “Margot was not the best of Giselles but Rudi’s arrival so totally rejuvenated her. It was unbelievable how she reinvented herself. That night the audience’s reaction defined ovation. A meteor had arrived. It was a privilege to be there.” For Drew that privilege extended to appearing on the same stage as Nureyev, “My role as Wilfred was tiny – but what you learned appearing opposite Rudi that there are no small roles, only small actors.”

© Francette Levieux. (Click image for larger version)

Twenty years after Nureyev’s death, his grave is a pilgrimage for a steady stream of visitors, in some degree confirmation of his desire for immortality. Currently flowers tied with red ribbons and tributes in gold Cyrillic script, “from the president of the republic of Bashkarstan,” are a reminder of Nureyev’s origins. But why an exhibition? While attending Marguerite and Armand at Covent Garden this year, a 20-something, first-timer at the ballet asked me, “Who were Fonteyn and Nureyev?”

Our sense of history is evidently fragile. The triumph of the Nureyev collection at CNCS Moulins is to make the many facets of his profligately talented, maddening personality so vividly alive still. Moulins is a *** destination, vaut le voyage as the Michelin guides recommend, well worth the detour.

You must be logged in to post a comment.