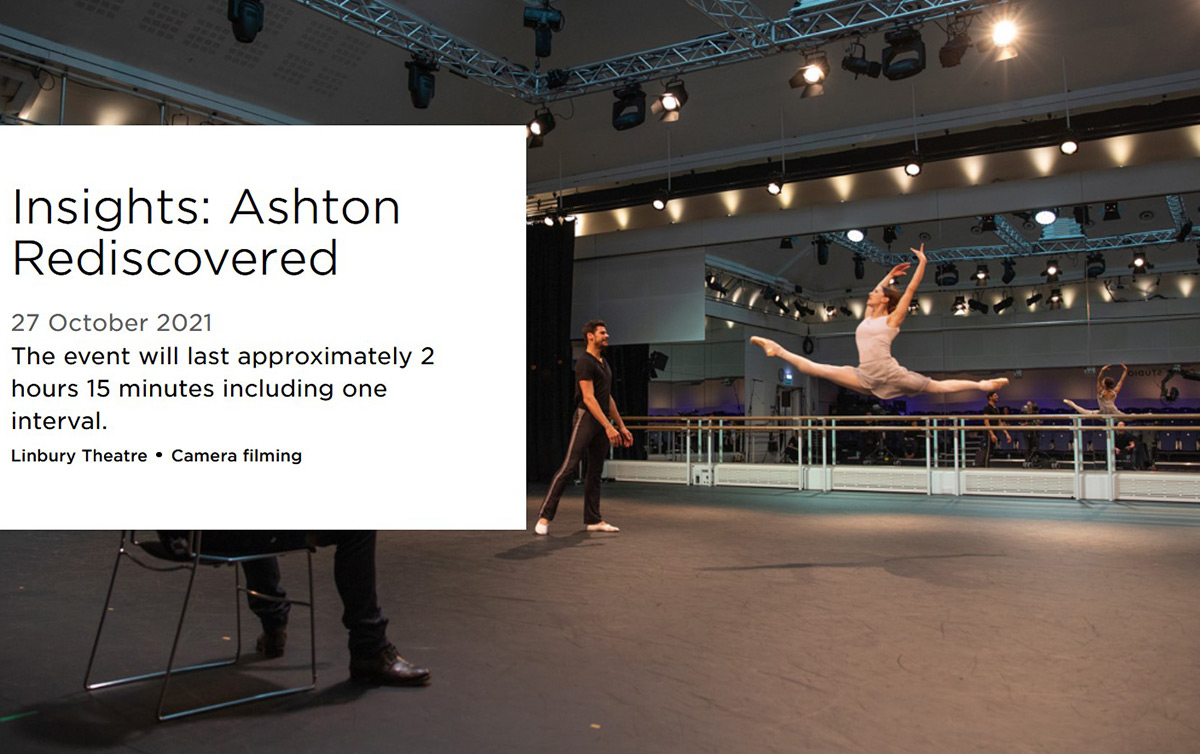

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

Insights: Ashton Rediscovered: Past, Present and Future

The Royal Ballet in association with the Frederick Ashton Foundation

London, Linbury Theatre

27 October 2021

www.frederickashton.org.uk

www.roh.org.uk

© Anthony Crickmay/ V&A Images/ Victoria and Albert Museum

Of Ashton’s hundred or so creations over six decades, only about 30 have been retained on film, in notation and in live performance. The Foundation has set about preserving ‘lost’ works through recordings of its masterclasses, in which original cast members pass on their memories to new generations of dancers. Three of the masterclass rediscoveries were performed by Royal Ballet members in the anniversary programme, along with a new re-creation of a gala number for Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev.

The evening opened with a filmed tribute by Robert Helpmann on the occasion of Ashton’s retirement as artistic director of the Royal Ballet in July 1970. Then followed a brief glimpse on film of young Alexander Grant bounding through the sailor’s dance from Rio Grande, a solo originally performed by Walter Gore in 1931. The programme’s compères, Gary Avis and Isabel McMeekan, came on stage to guide us through live excerpts from Ashton’s long career, which started before any British ballet companies had been formally established.

His early Foyer de Danse was given in 1932 under the auspices of the Ballet Club, which developed into Ballet Rambert. The performance took place in Marie Rambert’s tiny Mercury Theatre in Notting Hill Gate. Thanks to a black and white film made at the time, with Ashton as the Maître de Ballet and Alicia Markova as the Etoile, Ursula Hageli and Christopher Newton were able to reconstruct a group adage for six young women and a solo for the Markova ballerina, performed in the Linbury by Ginevra Zambon, a former Aud Jebsen Young Dancer who is now an artist in the Royal Ballet. (See Jann Parry’s account of the Foyer de Danse masterclass, 27 October 2019, for more background.)

© Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

With the cast in costumes resembling those in Degas’s paintings and pastels, the excerpt was charming, reminiscent of later Ashton ballets (and of Bournonville’s Conservatoire). Equally tantalising was the next fragment, from Ashton’s wartime Dante Sonata (1940). Birmingham Royal Ballet had first performed the reconstructed ballet in 2000, aided by Jean Bedells; two current BRB principals, Momoko Hirata and César Morales, came to London to dance the Children of Light pas de deux, originally for Margot Fonteyn and Michael Somes. Jonathan Higgins played the section from Liszt’s piano sonata (recently referenced by Thomas Adès for Wayne McGregor’s The Dante Project). For all the other excerpts, the pianist was Kate Shipway.

Next came the pizzicato variation from Act III of Sylvia (1952), danced by Anna Rose O’Sullivan. She’d been coached by Marianela Nunez, who had performed the role of Sylvia in the Royal Ballet’s 2004 revival of the full-length ballet. Ashton had created the solo – indeed, the entire ballet – to display Fonteyn’s range as a ballerina. O’Sullivan sailed blithely through the challenging pizzicato pointework and bends and turns of the upper body.

Ashton’s virtuoso choreography for male dancers was ably performed by Leo Dixon and Joseph Sissons in an excerpt from from Helpmann’s 1963 staging of Swan Lake. The variation for two men was part of a courtly pas de quatre in Act I, originally for Antoinette Sibley and Merle Park, Brian Shaw and Graham Usher. Ashton’s pas de quatre was also incorporated into Natalia Makarova’s staging of Swan Lake for English National Ballet (1989). In the duet, rehearsed by Christopher Carr, Dixon and Sissons were well matched as colleagues and competitors, with Sissens managing to tilt his head back during pirouettes - an Ashton speciality.

Isabella Gasparini danced Ashton’s Fairy of Joy variation from the Prologue of Peter Wright’s staging of The Sleeping Beauty for the Royal Ballet in 1968. The music is usually associated with the Jewel Fairies divertissement in Act III. For the Linbury performance, Gasparini had been rehearsed in the jubilant solo by Monica Mason, who had coached her for an Ashton masterclass in 2018. (See Jann Parry’s coverage of the masterclass.)

A highlight of the evening was Matthew Ball’s account of the Fisherman’s solo from Le Rossignol. Stravinsky’s opera had been performed as the Metropolitan Opera House in New York in 1981, with Anthony Dowell as the fisherman and Makarova as the Nightingale. The production was given at the Royal Opera House in 1983. In a 2017 masterclass, Dowell had recalled his solo and a pas de deux with the Nightingale, with William Bracewell and O’Sullivan as his demonstrators and Gary Avis observing as repetiteur. Avis taught the solo to Ball, who gave a full-out performance that transformed a little-known Ashton creation for an opera into a showpiece. (See Jann Parry’s coverage of the masterclass.)

Bracewell appeared in the final bonne bouche of the live programme, a new production by Wayne Eagling of a 1977 gala special for Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, originally called Hamlet Prelude, after its music by Liszt. The gala for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee was recorded and broadcast by the BBC. Retitled Hamlet and Ophelia, the pas de deux was subsequently performed with Eagling as Hamlet. Fonteyn, at 57, was already semi-retired: she announced her formal retirement at 60. Ashton’s choreography for her as Ophelia had many echoes of her former roles as Marguerite, Ondine and Giselle.

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

The pas de deux, an extravagant vehicle for two super-stars, was given a more restrained account by Bracewell and Francesca Hayward as Hamlet and Ophelia. A new backdrop by Sarah Armstrong-Jones featured abstract effects that changed colour and intensity with the shifting moods of Liszt’s Symphonic Poem, matched by Ashton’s choreography. The pas deux is essentially the ‘Get thee to a nunnery’ scene from Shakespeare’s Act III, in which Hamlet confounds Ophelia with conflicting messages about his feelings for her.

Tormented Hamlet – lots of spins, wild leaps and changes of direction – confronts bemused Ophelia. He embraces her, kisses her, then casts her to the ground over and again. She grovels at his feet; when he pulls her up, she stumbles pathetically off point, losing the balance of her mind. She gives back his ring and runs off when he casts it aside. He has a high-stepping solo of introspection, during which she drifts past him, trailing a veil of transparent watery fabric. He agonises, finally walking towards the audience, Albrecht-style, as the music ends.

Bracewell’s Hamlet was a student prince rather than Nureyev’s overblown tragedian. Hayward’s abused Ophelia told of her bewilderment with expressive arms and yielding backbends. Could a revival be on the cards? Ashton said of Marguerite and Armand that there was nothing wrong with a vehicle provided it works. I’m not entirely convinced that Hamlet and Ophelia does: it’s more of an Ashtonian pastiche for a famous couple than a ‘lost’ treasure by an old master.

Lynne Wake’s film, Frederick Ashton: Links in the Chain, was screened after an interval. She came on stage to explain that her film followed Ninette de Valois’s precept that the Royal Ballet should respect the past but concentrate on the future. Early films and previously recorded interviews with members of the company had become available for Wake to edit during lockdown. They were supplemented with recent interviews with present dancers, such as Marianela Nunez and Vadim Muntagirov, telling of their love of dancing his ballets, coached by those who had worked with Ashton. The Foundation has now established a shadowing scheme to enable a new generation of repetiteurs to watch and learn from original cast members so that his ballets can be presented as well as possible, in a way in which Ashton himself would have approved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.