© Carl Fox. (Click image for larger version)

Boy Blue

Blak Whyte Gray

★★★★✰

London, Barbican Theatre

12 September 2018

boyblueent.com

www.barbican.org.uk

The three phases of Boy Blue’s Blak Whyte Gray are contrasting in their movement but thematically linked: a journey through oppression, war and then salvation. And one that celebrates blackness. Directed by Kenrick ‘H20’ Sandy and Michael ‘Mikey J’ Asante, the return to the Barbican of Blak Whyte Gray, is again a triumph.

A stark opening portrays Gemma Kay Hoddy, Dickson Mbi and Ricardo Da Silva constrained by strait jackets, standing in cold, grey light. They are as motionless as stone statues until tiny twitches gradually stimulate their bodies. These build, sending violent judders coursing through limbs and heads. As the three ease into hip-hop popping, a fascinating interplay between action that travels like liquid through joints and hard, jarring snaps, we feel the terrible weight of their dismal ‘white’ oppression. While they struggle in their confinement, the perfection in which they articulate their catatonic trance and Asante’s prophetic urban music taints their miserable paralysis with a rare beauty.

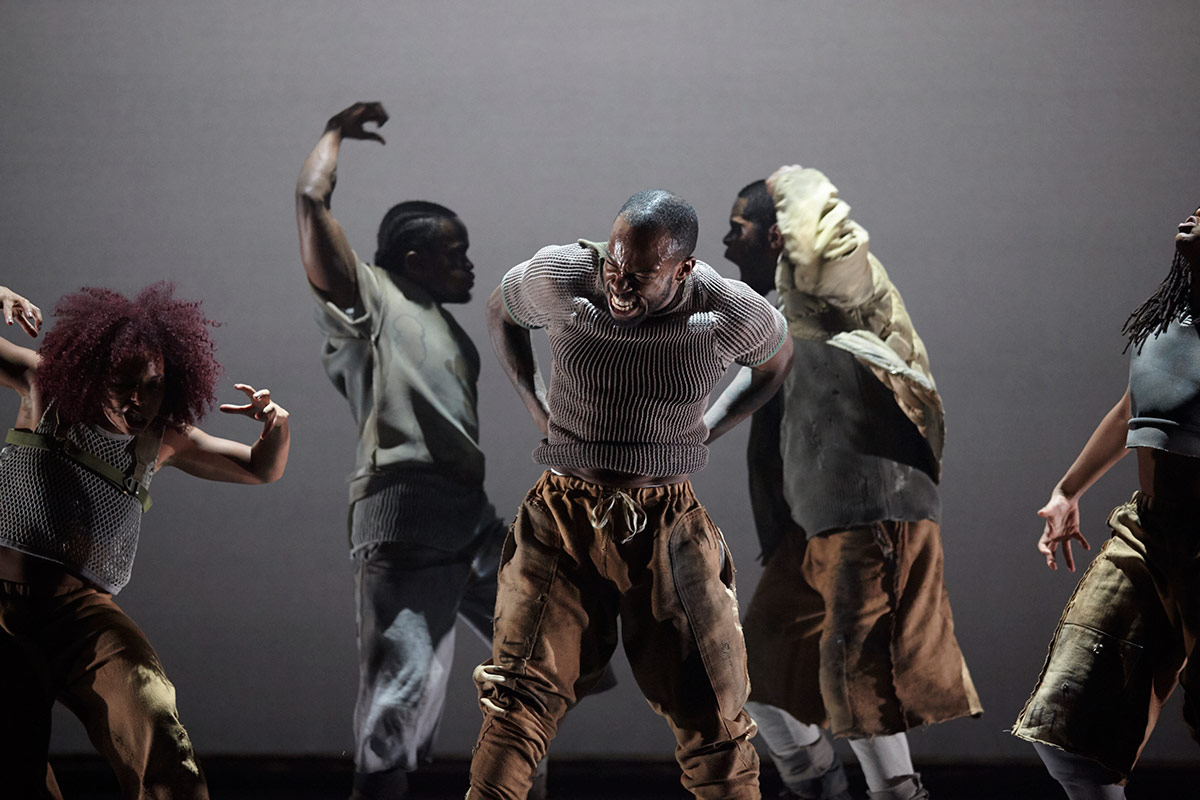

The next section, Whyte, brings more distress, this time through war and violence. As they enter shuffling along on their backs, washed in a desert light, the eight dancers resemble survivors in a dystopian place. Their boots, jackets and baggy trousers could be ad hoc army fatigues, as worn by rebel forces. They are suspicious, alert and aggressive. Here, as in the preceding Gray, the dancers unison work is particularly exhilarating. Huddles of bodies segue fast between hip-hop sequences and slow motion walking, playing constantly with dynamics of chaos and control. There’s more athletic activity than before, bodies leap off the ground, turning somersaults in space, virtuosic lifts, grimacing facial expressions and verbal exchanges. It’s such detailed choreography that I don’t want to blink. While gestures tend to focus on the holding of imaginary weapons, there are other reference points that create a diverse gestural language such as the voguing arms which frame the performers’ faces. Dramatic yet minimal lighting by Lee Curran also contributes to the wow factor of Blak Whyte Gray, as well as subtle political colour coding.

There’s both a warmth and a softer edge to Blak, conveyed collectively by the lighting, sound and choreography. Mbi is delivered on stage as good as dead and gently resuscitated by people who treat him like a long-lost king. His limp, lifeless body is passed from one person to another until they inject him with life, attitude and hope, as the others drape Mbi with rich red fabric and smear him in orange war paint. In this homecoming, music mixes hip-hop with majestic film anthem sounds to herald an ending, or a beginning.

© Carl Fox. (Click image for larger version)

The defensive energy of the previous section has gone and while movement still embodies heaps of attitude and edge, it contains greater eclecticism – less black urban and more African-dance derived. Now there are dances of ritual, of celebration and joy – folk dance steps that remind me of South African gumboot. There’s a visually thrilling moment in which large grey death masks descend from the lighting rigs. The darkened stage is illuminated by a crimson backdrop and ultra violet lighting which reveal the fluorescent patterns on the costumes as well as the war paint on human faces and masks. The latter are transformed into tribal regalia in a nod to, and reclamation of, African heritage.

While Mbi is signalled out as the chosen leader of the group, each of the dancers could as easily be spotted for their own unique styles and expertise and together they take the stage by force. Pushing themselves to beyond collapsing point, they smile all the way to the end.

You must be logged in to post a comment.