© Moran Norman. (Click image for larger version)

Alina Cojocaru

Alina at Sadler’s Wells: Reminiscence, Journey, Les Lutins, Marguerite and Armand

★★★★✰

London, Sadler’s Wells

22 February 2020

alinacojocaru.com

www.sadlerswells.com

Alina Cojocaru’s choice of works for her brief season at Sadler’s Wells provided an insight into her priorities as she reflected on her career: live music-making and dance-making that has something to say. She included two films by choreographer Kim Brandstrup that reveal something of her inner world, with no need for words.

The programme started with an overture: two musicians on stage playing Johan Halvorsen’s Passacaglia for Violin and Cello, based on a theme by Handel. Margarita Balanas as the cellist and Charlie Siem as the violinist communicated through their instruments – a joy to watch as well as listen – with no need for a dancer. Then came a pas de deux for Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg, to Arvo Part’s Spiegel im Spiegel, played by Balanas with Sasha Brynyuk as the pianist. The dancers’ partnership took the foreground in an intimate duet, Reminiscence, made for them by Tim Rushton.

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

Partners in life as well during their professional careers, they chose to make a show of handholds that are usually kept discreet in a balletic pas de deux. Kobborg embraces and steadies Cojocaru, lifting her effortlessly as she puts her hand on his shoulder. They play at catching butterflies together, a reference to his production of La Sylphide. She beckons him to come and dance side-by-side with her after they have parted for brief solo moments. They reprise their first encounter and end placing their hands on top of each other – a confirmation of their partnership and a mime gesture describing a growing child, their daughter.

The first of Brandstrup’s films features Cojocaru’s face in close-up as she visualises a dance to Couperin’s (recorded) music. It’s one of three portraits he made of dancers ‘marking’ choreography in their minds, unaware of an audience or even of the camera a few feet away from them. The unblinking gaze of Cojocaru’s dark eyes at the end reveals that she is elsewhere.

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

The second film takes her back to the Kiev State Ballet School, where she started her training. Born in Romania, she was talent-hunted as a youngster to be taught ballet in the capital of Ukraine, still in the USSR. The school building looks in sore need of repair, filmed almost in monochrome, with Part’s appropriate Fur Alina piano study playing in the background. Loving portraits of four of her teachers, their worn faces and hands wrinkled with time and endurance, pay tribute to their moulding of Cojocaru as one of the world’s finest dancers. This is how ballet technique has long been passed on, by touch and experience (though today’s teachers are no longer allowed to touch their pupils). This is why Cojocaru is so special: she knows that ballet is not just about legs and feet but the lines and angles and shading of the upper half of the body, as she demonstrates so beautifully, standing by a barre in Brandstrup’s film.

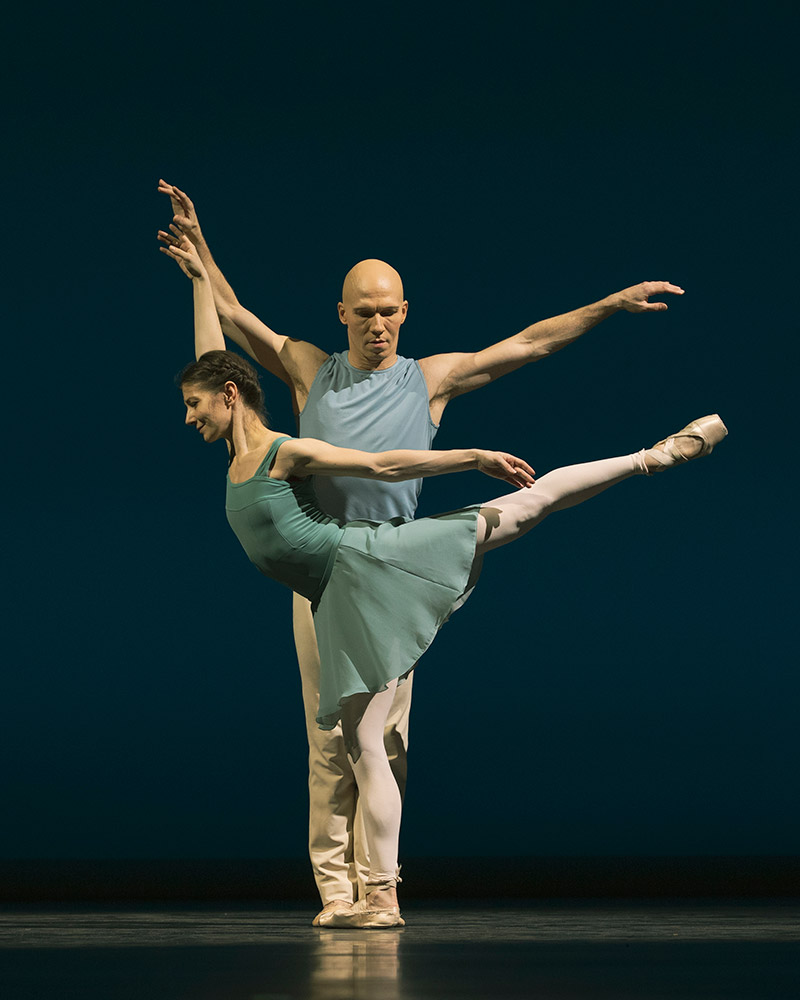

A work by Brazilian choreographer Juliano Nunes, Journey, uses Cojocaru as a macramé cord, intertwining her with two partners, Nunes himself and Dominic Harrison, a freelance dancer and choreographer. Set to sections from a film score by Luke Howard, with much wordless vocalising, Cojocaru’s knotty journey took her from one man to another, ending up with Nunes in loops and swoops of ecstasy. Stops and starts were meant to indicate new beginnings, but the disjointed piece didn’t reveal anything new about Cojocaru’s gifts.

Kobborg’s jeu d’esprit from 2006, Les Lutins (The Imps) also places her in a triangle with two men, in roles originally made for Steven McRae and Sergei Polunin. Virtuoso Charlie Siem impels the action with his violin from the side of the stage, as first Marcelino Sambé and then Takahiro Tamagawa comment on the music in capricious beaten steps and whirlwind spins, competing with each other and the violinist. Cojocaru emerges as a tiny, tomboyish flirt, looking absurdly younger than her 38 years. She gives the lads short shrift, falling deliciously for the fiddler instead. Kobborg’s comic touch as a tyro choreographer lightens the first half of the wistful, fragmented programme.

© Andrej Uspenski. (Click image for larger version)

The second half is given over to Frederick Ashton’s 35-minute Marguerite and Armand, created in 1963 as a vehicle for Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev. Cojocaru never danced it while she was with the Royal Ballet, though she has appeared to great acclaim in John Neumeier’s three-act version of the same story, La Dame aux camélias. Ashton’s one-act ballet crams in the story of the courtesan’s sacrificial love for callow young Armand, with three changes of costume for Marguerite and stagey tableaux for her admirers (here a motley crew of dance extras).

As Armand, Francesco Gabriele Frola (who splits his time between English National Ballet and the National Ballet of Canada) has the looks but not the panache for Nureyev’s idealised appearance in the ballet’s opening flashback, a romantic icon if ever there was one. Frola was more accomplished once Armand was able to show anger and then repentance in his treatment of Cojocaru’s frail Marguerite. She is so light a dancer that he couldn’t grasp the gravity of her decision to reject him at his father’s insistence.

© Moran Norman. (Click image for larger version)

In this production, with Sasha Grynyuk pouring out Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor from the pit, the heart of the story became the relationship between Cojocaru’s Marguerite and Kobborg’s Germont, Armand’s stern father. Ashton apparently intended the role, created on Michael Somes, to be a stark, enigmatic one, a figure of fate. Kobborg makes Germont so sympathetic that attention shifts unduly to his feelings when he leaves Marguerite’s deathbed scene to let her have her last moments alone with his son.

Cojocaru gives her Marguerite a nuanced hinterland. Covertly consumptive, she’s politely curious about Armand at their first encounter instead of being struck by a coup de foudre. She trusts Ashton’s choreography to show how captivated she becomes by him, against her better judgement. Her renunciation is heartbreaking, as is her gentle reproach when he denounces her in public. She dies in his arms after seeming to fly from them, already a spirit. It’s a remarkable performance, flimsily framed by an inadequate production.

You must be logged in to post a comment.