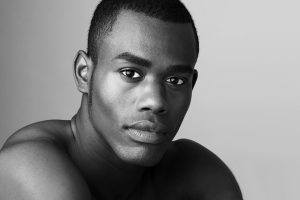

© Fabrizio Ferri. (Click image for larger version)

Balletic Musings from Alexei Ratmansky

(A Continuing Conversation)

Since 2008, when the Russian choreographer Alexei Ratmansky made his first ballet for a New York company, Russian Seasons, audiences in that city and around the world have seen a steady stream of his works, from Concerto DSCH to Seven Sonatas, Namouna, The Bright Stream, and on to his recent Shostakovich Trilogy. Ballet lovers are beginning to form a clearer picture of his style, his approach, and his way with dancers. As with any complex (and developing) artist, what we get is a moving image, an ever-evolving canvas that expands and shifts before our eyes. We can absolutely not predict what will come next. And yet, certain features return again and again, like a signature or a genetic code. An interest in asymmetry, in complexity and layering. A keen and highly personal musicality that teases out emotions and images from the music. A fascination with the history of the form, particularly the ballets and music of the early Soviet period. (This historic hyper-awareness infuses his dances with a palette of stylistic references.) A desire to tell stories and awaken the dancers’ imaginations. A kaleidoscopic use of the stage. Generally speaking, a human touch and a sense of play that comes close to corniness. And wedded to that, a whiff of sincerity that leaves space for stylistic games and ironic twists. And to my eye, his most remarkable quality: a vigorous, jagged, un-sentimental use of ballet technique that makes it feel alive and of our time.

What follows is an edited composite of various conversations I’ve had with Ratmansky over the course of the last few years (the earliest was in 2009, when I wrote my first piece on him, for The Nation [Ratmansky Takes Manhattan, Oct 2009]. Over this brief period, we’ve discussed his background, his approach to choreography, his influences, and even a few of his doubts. In conversation, he is soft-spoken, quietly intense, and thoughtful. Most of the time, one has the impression that he is itching to run off to a studio and get to work. And yet he answers earnestly, patiently, and without the slightest self-aggrandizement. I think these qualities come through in his responses below.

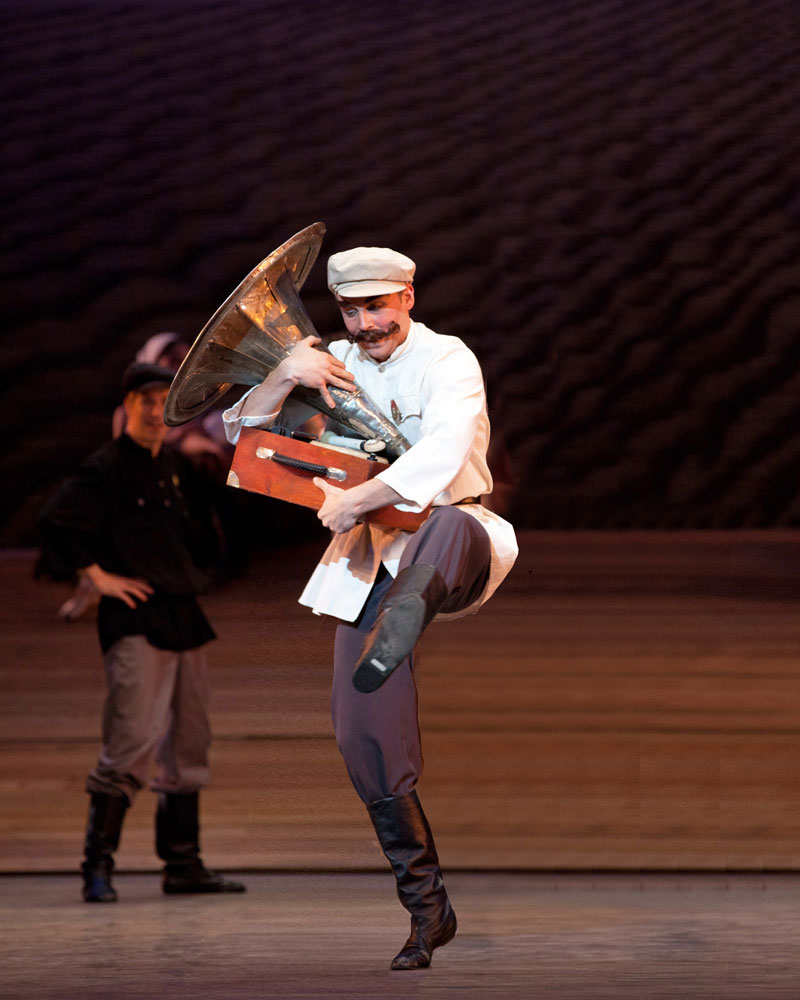

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

MH: What first led you to dance?

AR: We always had music in the house. On TV, in Kiev [where he grew up], they showed ballet and music quite a lot. My parents took me to the symphonic concerts, but it wasn’t more interesting to me than doing gymnastics or playing with my friends. But when friends would come over, my parents would say, do you want to dance for them? We would put music on, and I would do my improvs and be happy. And my parents’ friends would tell them, “you should bring him to the ballet school.” So it wasn’t my decision. I was ten years old when I started, and it was tough, but after three or four years when I started to succeed, I liked it. At some point I realized I wasn’t the best in the class. There I was, trying to get my leg up, and I thought, ok, where can I succeed? And no-one else was doing choreography around me, so…

MH: When did you first start making dances?

AR: I was in Kiev [dancing in the Ukrainian National Ballet] and I just tried to do something. I would grab someone in a corridor and go into a studio. I had projects, and I would ask a few people, and we would have one or two rehearsals and then they would of course disappear because there was no prospect of performing it. I would go to the artistic director and he wouldn’t really listen. So I had to find my way. There were charity performances and I managed to choreograph two duets to Shostakovich, using some of his early pieces. Then part of the first symphony. I called it “Sylphide 88,” because it was done in 1988. For that, I had a big group, eight girls or something, and a few men. I didn’t have any style then. The first real opportunity to choreograph and have a piece presented onstage was when I was dancing in Winnipeg [at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet]. They had a workshop – we never had workshops in Russia. But in Winnipeg the director, John Meehan, said “anyone who wants to choreograph, please do.” I was so happy. I used the finale of Shostakovich’s first piano concerto.

MH: Were you very influenced by your experiences abroad?

AR: When I worked in Canada as a dancer, it was my first trip to the west, and it opened my eyes. For the first time, I danced Balanchine, Tharpe, Neumeier, Ashton, Robbins. It was just an amazing experience. And then I auditioned in NY to dance for NYCB and ABT a few times, with no success, in the nineties. I went to Europe and danced in Denmark for 7 years. The Balanchine tradition, Balanchine’s philosophy, his ethic, his idea of the music coming first, was very important to me.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

MH: What Balanchine ballets did you dance?

AR: Tarantella, Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux, Allegro Brillante, Square Dance, Symphony in C, every part. Well, second part I just rehearsed but didn’t dance. Rubies.

MHL Which was your favorite to dance?

AR: Square Dance.

MH: Were you very influenced by your experience of dancing Bournonville ballets in Denmark?

AR: I think so. Those little changes of direction are so beautiful, so three dimensional. And the unexpected changes.

MH: Were does your intense interest in ballet history come from?

AR: I sense a big support from history. You can’t really go to the university and learn choreography. I guess you can be an apprentice, but I never had that luck. So for me it’s the only way to learn the craft. Staging another choreographers’ ballets is a great, great school. I discovered that when we did Le Corsaire at the Bolshoi. We had about sixty minutes of original Petipa steps. My co-choreographer Yuri Burlak and I really wanted Petipa’s part of it to lead us. So everything that we knew had come later we got rid of. It was a really satisfying experience looking through all the notations and archives and trying to dig back to what was there. I’ve also re-staged ballets by Massine with new choreography, like Scuola di Ballo [for the Australian Ballet], as well as Lopukhov’s Bolt and The Bright Stream, and Fokine’s Golden Cockerel [for the Royal Danish Ballet].

MH: You’ve worked a lot with Shostakovich’s music. What first drew you to it?

AR: The theatricality. I was beginning to get interested in drama theatre. I went to see some Moscow productions. It was my sixth year at the Bolshoi school, the first time they let us go out alone. Before that we always had to be in a group. I was fourteen or fifteen. My parents lived in Kiev and I was in Moscow. We had to sign a paper and say where we were going. I think I was the only one who went to the drama theatres. Somehow it all clicked together. By that time I had already decided I wanted to be a choreographer. We didn’t have choreographers in the school and the only choreographer we knew was Grigorovich.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Why did you decide to take on The Bright Stream, in 2003, for the Bolshoi?

AR: Gennady Rozhdestvensky, the great Russian composer, made a recording of The Limpid Stream in the early nineties. Of course I knew the title from our lessons in the history of ballet. But when I heard it, it seemed to me very unlike Shostakovich. It was almost straightforward. Because with Shostakovich, there is always something hidden underneath the surface; that’s the way most of the true artists of that period worked, I think. Here, you can sense his effort to be simple, to be approved by ordinary spectators, by the authorities, by hundreds of critics who were really killing him at this time. I think there was a lot of jealousy, because he was not even thirty, and his works, like the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, were so successful. In two seasons it was performed 200 times; it was like Broadway. And Bright Stream was immediately transferred from Leningrad to the Bolshoi after the premiere. It was a huge success with the public and with the critics. His talent was so big and true that he couldn’t really believe in the optimistic stuff that he was supposed to do. You absolutely can hear the sardonic irony in the music for The Bright Stream.

MH: Many of your ballets seem to reflect a sense of play.

AR: I use that in most of my work. There is never drama or tragedy without a lighter side. But it’s important not to force the humor. It’s how you work with the dancers. It’s very important for them to understand it should never be forced.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Is that balance of playfulness and seriousness part of what drew you to The Bright Stream?

AR: Yes, I think his way of reflecting reality was hugely influential on me. It’s a comedy, but also a very human story. It shouldn’t be one color. It’s boring if it’s one color. It’s a serious lesson, the moral of it, the husband who does not appreciate his wife. He looks around, but she’s the real treasure. At the same time, we are playing a stylistic game. People don’t make ballets with a message anymore, so we can look at how they did it before, and take something from that. You have a score, which is very balletic and historical, and you have a story which you can’t really take too seriously, with tractor drivers and milkmaids, so of course there will be irony, there will be stylistic games, and at the same time it can’t be just that, there also needs to be some truth in it. I really encourage that in the dancers, that something serious comes through, like serious love, or serious jealousy, serious sadness. This gives the work weight, and makes it resonate not only on a post-modern level, but also on a deeper level.

MH: Do you ever feel like you “speak” with Shostakovich?

AR: I would love to think that. Yeah. There is some kind of… I seek support. When I was choreographing Psyché in Paris I went to the cemetery where Franck was buried just to look at his tomb.

MH: You’ve met Shostakovich’s widow, Irina. What was she like?

AR: I’ve seen her a few times. She’s very reserved. She liked the ballets Bolt and the Bright Stream [both created for the Bolshoi]. And I’ve sent her a dvd of DSCH [created for New York City Ballet]. She called me and said there are new recordings of his music-hall scores. She said, “you seem to be dealing nicely with his light music,” so she sent me the recordings and the scores. When you talk to her you get a little closer to the man.

MH: Is sincerity important to you?

AR: Yes (pauses). It’s something you can’t imitate. A way of finding something that you feel is important.

© Fabrizio Ferri. (Click image for larger version)

MH: You often include ballet masters in your works.

AR: I think the older roles should be done by older people. The whole company is involved. It’s inspiring. They bring experience and understanding. I think it’s something I learned in Denmark, because they have these great character dancers. In the programs, they are listed before the principals. They are the core of the company.

MH: It builds the idea of the company as a community.

AR: Well, a company has to be like that. The company has to be a family.

MH: The use of the whole company also makes it easier to tell stories. What’s your attitude toward abstraction in ballet?

AR: The audience always wants stories, but you can tell stories without telling stories. It’s hard to get the audience’s attention with only the steps. Because the audience wants to see, if not a story, then how the steps relate to each other. History goes like that, during some periods, there is an emphasis on working on structure and steps, and then in other periods, the emphasis is on story. It’s a process that goes to one extreme and then the other. In ballet we can’t be as abstract as abstract painting or music – of course, music pulls real emotions out of you. This is not abstract. And in dance, it’s human bodies. Every step, every gesture, the audience can make connections with the images. The men touch the women in the partnering, and you can’t touch your partner, your girl, without any feeling, because it’s not a table, it’s a human being. So there are so many levels that are not verbal. When a movement is done by Julie Kent or Gillian Murphy or Diana Vishneva, it says different things.

MH: Do you perceive a difference between the musicality of American dancers and that of Russian dancers?

AR: There is a huge difference in the musicality. I often found Russian dancers unmusical. It’s something… I think it’s Slavic, they don’t have the rhythm, it’s not about the rhythm, it’s about the melody. Russian dancers, they sing, and American dancers do the rhythm with their feet. That’s what I see from my experience of working with both. It’s partly because of Balanchine; strange, since Balanchine and Stravinsky were both Russian. If you look at the Bolshoi and Mariinsky dancers now, it’s always off the beat. But they have other qualities. They really sing with their body, with their port de bras especially, and the head and shoulders, and back, all that is very much involved.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

MH: The ballets you’ve made for New York City Ballet are quite different form the ones you make for American Ballet Theatre. Do you feel that the companies are very different?

AR: They’re different, and I think I’m trying to sense the fortes, the different sides of the dancers in order to present them better. ABT is more theatrical. They’re good at creating characters and telling stories.

MH: A lot of the movement in your ballets has a weighted feel, something one associates more with modern dance than with ballet.

AR: But just imagine if classical dancers do this in classical ballet, it will look even better, more alive. I look for that in the movement. I like more plié, I like bigger steps and covering space and upper body answering the movement. The head too. The head and neck, using the weight of the head. I learned this from people I worked with. I have a feeling that I found a vocabulary that I use, and every time I add a little bit to this vocabulary, but still using what I already have. The more new stuff I add, the better it feels for me.

MH: You also seem to be very interested in complexity and layering.

AR: I guess so, yes. A simple step, in my eyes, would need something else to happen. Sometimes I over-complicate things and there is a danger there. You only have two eyes, you can’t really see; if you look there you miss what happens here. In front of the big painting you have to spend time to look in different places. I just want the picture I have in the studio to satisfy my eye. At the same time, to tell you the truth, I would love to make something simple and strong. The one time that I got a little closer was with Concerto DSCH. I think I took the inspiration from the Flames of Paris choreography [for the Bolshoi], by Vasily Vainonen, the “Dance of the Basques,” which is really amazing.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

MH: At what point do you start to form your ideas for a ballet?

AR: I let it be quite a spontaneous process, because I find that it forces things if you try to get the idea before you go into the studio. You need to have a vague idea of the whole thing, but the ideas evolve when you find the steps; the steps dictate the routes for development. I may have an outline, but very loose.

MH: And what about the steps? Do you prepare ahead of time?

AR: I’ve tried different things. I tried being completely prepared, every single step and partnering passage. And then I tried being empty and coming to the studio and improvising. I find that for me it works best if I know the music, I have the images in my head, and I have basic movement ideas, but I don’t plan the whole thing, and let the work evolve organically. Every day is different. Sometimes you don’t have the whole cast, sometimes you have someone very eager who does something amazing, it really directs you. Every day directs you in a certain way and if you’re really attentive to what’s happening in front of your eyes and trusting the dancers to lead you somewhere, I think it works the best.

MH: Do you usually work straight through from beginning to end?

AR: It depends on the music – sometimes the music leads through to the end, sometimes I pick up with the part that I feel better about and that I have a feeling I can work with. It’s an intuitive process, I think, so I might do a part that I know how it should look, and then see what the connections would be.

MH: Do you use any kind of notation system?

AR: I used to try to write everything down, but it takes so much time, and then you go back to it and you can’t read it. Let alone someone else. So how I prefer to work now is I write down all the counts, the structure of the music, and I can give the counts to the dancers. I wake up at 6 am and before 12 or 1 when we start rehearsing I really have in my mind where I want to go. When the ideas are from that morning, you have them in your head. Then I rush to give them to the dancers and then it’s their responsibility (laughs). And I have a great assistant [at ABT], Nancy Raffa.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

MH: How fast do you work?

AR: A minute-and-a-half [of choreography per day] is fine. Two minutes, you have to be very focused, and more than two minutes is very stressful.

MH: Do you ever suffer from self-doubt?

AR: Yes. [long pause] Yes, a lot. Sometimes you feel wow, this is really working well, then you see the premiere and it’s just boring. What was so exciting about it? Or sometimes you doubt that it’s working, and then I call my wife. Of course she’s not objective, but she’s skeptical and rather on the critical side, always. Which is great. Because you don’t need to hear that you’re great. Well, sometimes you do. We’re a team and if she tells me, “think better,” or “I’ve seen that before,” then I change it.

MH: You tend to work with pre-existing scores. Do you have an interest in working with living composers?

AR: I have so much music that exists and I want to work with, but there’s a Russian composer, Leonid Desyatnikov, who has written new music for me. It’s very risky [working with living composers]. But I’m very fine with interpreting music that exists.

MH: There is a feeling in some circles that ballet is in peril. In her book Apollo’s Angels, the historian Jennifer Homans wrote that she feared that ballet was dying. Do you ever worry about that?

AR: I don’t feel that. And even if it is, I don’t care. I do what I love, and I often get inspired by what I see. I’ve had the opportunity to work with great dancers. I’m happy about it. Not to worry.

You must be logged in to post a comment.