© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

The Australian Ballet

Icons bill: The Display, Gemini, Beyond Twelve

Melbourne, State Theatre

8 September 2012

www.australianballet.com.au

Every dance company has at least one iconic image – a photograph that captures the essence of a dance work, unique to its time and utterly individual to the company. For the Australian Ballet there are several contenders, but for me it is a photograph taken in 1964 of Barry Kitcher and Kathleen Gorham in Sir Robert Helpmann’s The Display. Kitcher is wearing The Lyrebird costume – a full feathered mask with wide-set eyes and a wingspan of glorious tawny and brown feathers reaching nearly five meters. He looms over Gorham, the young girl in a pale dress. She is kneeling, bent over backwards, her uplifted face revealing supplication, or perhaps surrender to her status as dominated prey. The image is sinister, chilling and sexual, reflecting the violent nature of the ballet that begins with a picnic and ends with a rape – tough issues to dance about then, as they are now.

The Display is one of three works reconstructed for the Australian Ballet’s Icons program. It is the work chosen to represent the 1960s, the first decade of the company’s fifty years. Glen Tetley’s elegant, fierce, and abstract masterpiece, Gemini, and Graeme Murphy’s sentimental Beyond Twelve represent the company’s repertoire from the 1970s and 1980s. Icons is – as the Australian Ballet’s triple bills always are – an ambitious program, designed to challenge a wide and diverse Australian audience.

In The Display, The Outsider (Kevin Jackson) comes upon a group of young people. The men and women are typical Aussie stereotypes of their time; the men following The Leader (outstandingly performed by Rudy Hawkes), a larrikin who punctuates each double tour with a swig from his stubbie (Aussie slang for beer). He is handsome but vapid, aware of his power over his mates, the gaggle of girls who hang off his arm and The Girl (Madeleine Eastoe), his pretty girlfriend. The girls wander around admiring their blokes, prancing across the stage to avoid the arc of a football but never attempting to join in the game. This is, after all, a sport for real men – a display of power, virility, and masculinity as potent as the mating dance of the lyrebird.

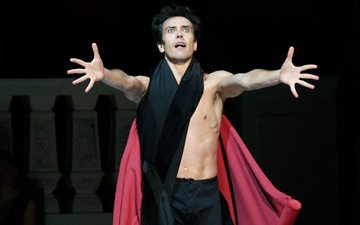

The Outsider looks different from the rest (he wears an outfit of red and blue as opposed to the pinks and grey shirts and slacks of the group), and he moves differently as well, showing off for The Girl with a controlled solo of balances and pirouettes. He rejects the consuming blokey culture, turns his nose up at the taste of beer and breaks the strict gender segregation of the group.

The Girl plays her old beau, The Leader, against her new admirer before allowing herself to be seduced. Echoes of bird calls ring in the air as if to remind us that, no matter how strictly the players abide by the rules of the game, their genders or this culture – we are actually in the uncivilized, wild and dangerous bush.

At the climax of the ballet, the Leader finds The Outsider with The Girl and beats his rival unconscious. Filled with rage, humiliated by his cowardice and blaming The Girl for his injuries, The Outsider attacks her. He rips her skirt, pushes her head into the ground, hauls her from one lift to another with a yank of the arm. The pas de deux, though highly stylized, is unnerving.

At the end The Girl is left alone with The Lyrebird. The final image of the ballet is the iconic one from the photograph – The Girl bent over and obscured beneath the span of an enormous bird as though she has been swallowed alive.

It is a strange ballet, and ultimately an unsettling one, because every male is a villain. As much as we want to sympathize with The Outsider, it is he who takes his humiliation out on The Girl, punishing The Leader through her with his sexual violence. His sin is against The Girl, but it is also against the group. In not playing by the rules he has made himself more The Outsider than a costume could ever render him.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

At the time of its premiere in 1964 The Display shocked its audiences. Highly sexualized, violent and thoroughly modern, the ballet divided audiences and critics. But, seen in the context of Helpman’s life, the choices within the work begin to make sense.

Helpmann was a man who, like so many others of his generation, left Australia to pursue a theatrical career overseas. He was plucked from relative obscurity by Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, during one of her tours to the Antipodes and, like a handful of other talented Australian dancers, he snatched the opportunity to train overseas where the climate was more accepting for young dancing men. Accusations of ‘sissy’ flew fast and thick for men who chose dance as a career and if his personality later in life was anything to go by, Helpmann was probably a particularly flamboyant child and not at all suited to the sleepy streets of conservative South Australia.

When Helpmann returned at the behest of Dame Peggy van Praagh to make The Display on the company in the early 1960s, he was returning to Australia as a mature star – in the ballet world, in theatrical circles and in Hollywood (the ballet was dedicated to actor Katharine Hepburn).

It is not hard to see The Display as Helpmann thumbing his nose at masculine Aussie culture. In fact, we know that he wanted the work to stand as an indictment of Australian society and culture. The work mercilessly sends up the bullies, the bravado, the cowardice and the underlying rage within his male characters. Every male in this ballet is a villain, every female is naive and coquettish, the comedic lyrebird is a predator, and there are fools at every turn.

The use of Aussie Rules Football and boxing moves, interspersed with the vocabulary of classical ballet, brings a sense of masculinity to his characters. The actions would have been familiar to an audience then, as they are now, used in such a way as to highlight the superficiality of the stereotypical Aussie larrikin and to mock a sports-mad nation.

It may seem strange that Helpmann chose a lyrebird for his predator, after all, this is the land that shelters some of the most deadly animals in the world, spiders, snakes, sharks and more. Even the seemingly cuddly platypus could kill you with its stinger, and that adorable marsupial and national icon, the koala, could well tear your eyes out with its claws on a eucalyptus-fuelled whim.

The male lyrebird, that humble brown avian, is known, not for poison, but for an extravagant mating dance in which he comically struts and skips with a display of gorgeous tail plumage. This is hardly a nightmarish creature.

However the lyrebird is actually the Great Deceiver of the Australian bush. This braggart perfectly mimics sounds and calls he hears in an attempt to win a mate, matching sound with his extravagant movement. Like The Outsider in the ballet, a man whose kind and romantic movements hide the rage within, the lyrebird can seem to be anything he pleases. It is no wonder The Lyrebird in Helpmann’s The Display becomes the symbol of both dangerous masculinity and a lack of personal independence and integrity. The representation of a benign, comical bird as the predator, ‘The Male’, may have been Helpmann’s way of reminding his audience to look beneath the surface of gender stereotypes and cultural values.

This reconstruction of The Display has received mixed reviews from Australian critics. However, even nearly half a century later, there can be no doubting the bravery of Helpmann in making this work. I wandered into the foyer at interval wondering if, as the saying goes, ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same.’

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

The second work in Icons was Glen Tetley’s 1973 abstract masterpiece, Gemini. Like The Display, Gemini drew criticism at the time of its premiere for the sexualisation of the dancers; in this case, it was the iridescent spandex yellow unitards that were cause for concern. However, the unitards (designed by Nadine Baylis) were a brilliant choice then as they are now, revealing the muscle and sinew of the human body against a graphic, almost stark, set design of horizontal bars.

Principal artist Lucinda Dunn captures the essence of Tetley’s work, which fuses American modern dance and classical ballet with a sequence that begins with an arabesque en pointe and transitions into a slow contraction, a concave arc that ripples from pelvis to the crown of the head. Dunn curves and undulates as though her insides have been scooped out, delivering a sublime performance that outshines that of her fellow dancers with its amazing strength, flexibility and athleticism.

Icons finishes with Beyond Twelve, a work created by Australian choreographer Graeme Murphy in 1980. This work possesses everything that we love about Murphy’s work. It is playful, poignant and irrepressibly tongue-in-cheek. The three-act work tells the story of a boy who chooses a career in dance. In ‘Beyond Twelve,’ the boy (Charles Thompson) must decide between the footy field and a dance class, where a string of girls are suspended upside down by the players, still tapping the time step in midair.

In the second act, ‘Beyond Eighteen,’ our boy (now played by Christopher Rodgers-Wilson) falls in love at the barre. His duet with his dancing partner, the First Love, (a role beautifully performed by Lana Jones) is mirrored upstage by his past self – the young man still in his football jersey, lifted and partnered by his mother.

In ‘Beyond Thirty,’ the boy has become a man (Adam Bull), who still feels the echoes of his former selves dancing with him. A pas de trois sees each successive man lifting his former self, carrying a past life on his shoulders like a talisman of experience and knowledge.

The last scene in Beyond Twelve is particularly touching. The pas de deux between the man and his First Love ends, the lights come up to reveal the bowels of backstage and the woman goes home with her real-life partner. As he stretches out supine on the floor, we see the man accepting the chasm between his fantasies, his memories, and his desires – and the reality of an ageing body and a mature mind. There is something poignant about the way he throws a towel over his shoulder and leaves the stage, turning his back on the audience in preparation for the next ‘beyond.’

It is a moment of sadness but also of expectation and acceptance, and it is not hard to see Murphy himself in this role – a man whose celebrated career as a dancer with the Australian Ballet transitioned into a career behind the scenes as choreographer and director.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

It is interesting that Icons starts and finishes with Aussie men playing Aussie Rules football, balancing the expectations of behaviour for men and women in leisure in the most fundamental way for this country. In Helpmann’s The Display, the game playing is competitive, as the men leap and spin between passes. The game in Murphy’s Beyond Twelve is youthful and symbolic of the boy’s innocent childhood – rather like a moving sepia memory, recalled from long ago. In both cases, the works are about men in Australia told in the language of movement and utterly idiosyncratic.

Tetley’s work stands out for its differences; unlike the two Australian choreographers, Tetley’s inspiration for Gemini was the vast Australian landscape, reflected in expansive gestures and clean lines but interpreted through a strangers’ eyes.

For all its surprises, Icons is actually a fairly typical program for the Australian Ballet, representing the identity of a company that always has one foot in classical ballet and another in contemporary dance, in new and old, and in Australia and the International. It is not an easy thing to be so much at one time. The simple fact that this company of dancers performed so beautifully in all three works – three works so very different in style, technique and characterization – speaks volumes about their skills.

You must be logged in to post a comment.