© Walter Carvalho. (Click image for larger version)

Companhia de Dança Deborah Colker

Tatyana

London, Barbican Theatre

31 January 2012

www.ciadeborahcolker.com.br

www.barbican.org.uk

Deborah Colker’s Brazilian Tatyana is a maverick alternative to the ballet and opera versions of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. For those who didn’t already know the story and couldn’t afford the souvenir programme, the Barbican provided a synopsis sheet, complete with a guide to the colour-coding of the 16 dancers representing the four main characters, plus two Pushkins. Good luck with that.

Colker is more concerned with emotional drama than narrative exegesis. Her Tatyana is all about thwarted love: delirium, then disillusion; dreams of what was meant to be but which fate prevented. The action takes place in two different surreal contexts, designed by Colker’s frequent collaborator, Gringo Cardia.

Act I is dominated by a stylised wooden tree, from whose branches dangle books as leaves. The stage picture looks spectacular, with multiple Tatyanas (in pink) perched on high, numerous Olgas (in green) dancing below with virile Lenskys (yellow), while Onegins (blue) twirl their canes superciliously. An acrobatic Pushkin in black leather clambers amongst them, part voyeur, part Svengali. A Russian-themed score of chunks of Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev and others selected by music director Berna Ceppas batters the eardrums.

A hefty clue to where we’ve reached in the plot is the introduction of huge black quills: aha, the letter-writing scene. One Tatyana, tall Amalia Alzueta, writhes lasciviously like an animal on heat in the middle of the tree, while three others on upper levels brush the feathers longingly across their bodies. When the quills are dropped, Pushkin picks them up tidily and twines himself around a green Olga, presumably dooming her innocent happiness. Dielson Pessoa as the male Pushkin has bleached his hair to resemble blonde Colker as his female counterpart. The unfortunate result is that he resembles Jimmy Savile on the prowl. (Pushkin the poet was dark, thanks to a slave forebear who had been a page to Peter the Great.)

© Walter Carvalho.

After some feisty folk dances, the fatal duel is signalled by Lensky(s) parading with a fan, whose snapped closure sounds like a pistol shot. Onegin is meanwhile armed with a top hat and sword stick. Very confusing, these ‘symbolic’ props. Pessoa-Pushkin hurls himself in distress into a manège of barrel turns: is the author upset by his plot or foretelling his own death in a duel?

Colker’s choreography in the first act uses Pessoa and Alzueta balletically, contrasting their long lines with tight unison routines for the others. Men move martially while barefoot women writhe sinuously or fling themselves in daredevil plunges from the branches of the set.

Everything changes for the second half. The tree has gone, replaced by an elevated platform at the back of the stage. Eight veiled Tatyanas appear on pointe in frilly white leotards: bayadères in knee pads – not a good look. They reproach eight Onegins in black capes down below, to Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto. There’s no Gremin in this limbo to explain Tatyana’s dilemma. Instead, the two Pushkins take turns to express anguish: Pessoa is a gymnastically tortured soul, Colker a sensitive one. Undulating and flickering her fingers, she’s partially shielded from view by laser beams darting across mesh screens; her age was all too apparent in her Act I solo, surrounded by lithe young dancers.

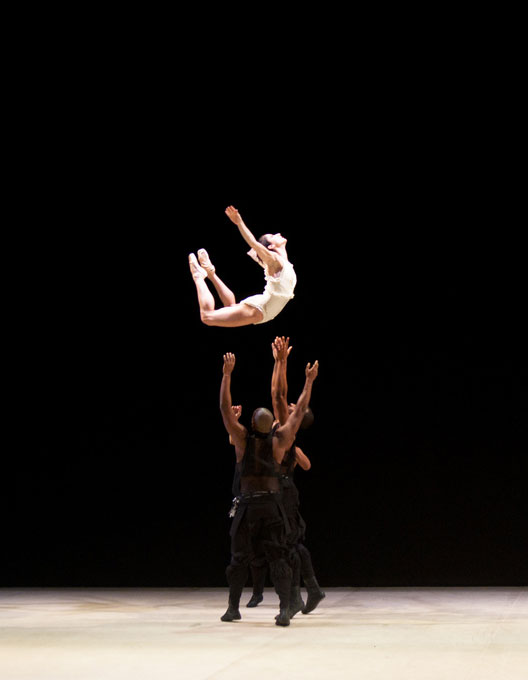

© Walter Carvalho. (Click image for larger version)

Colker’s inadequacies as a choreographer are exposed in agonised pas de deux for mature Tatyana (in unfortunate long white gloves) and multiple Onegins. The central duet is a parody of Cranko’s inventive pas de deux. The Tatyana dancer is manhandled into splay-legged positions, spun like a top in dizzying pirouettes, heaved upside-down.Versatile though these dancers are, they can’t accomplish searingly romantic lifts. No wonder all the Tatyanas come to their senses if this is what true love does to them. They retreat to their shelf and rise upwards at the end, leaving Onegin(s) to fall apart.

By abstracting and generalising the emotions in Pushkin’s verse-novel, Colker has rendered her account of the story completely incoherent. The 18 scenes listed in the synopsis are indistinguishable, as are most of the characters in terms of the way they move. Her bids at ‘contemporary ballet’ choreography are execrable. On past form, she’s better at assembling unrelated sequences of acrobatic skills, using ingenious props and not bothering with narrative.

You must be logged in to post a comment.