© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

New York Theatre Ballet

Legends & Visionaries: Three Shades of Blue, Run Loose, Jazz, Libera!, Ten Imaginary Dances, Light Flooding Into Darkened Rooms, Short Memory

New York, Florence Gould Hall

24 January 2014

www.nytb.org

Dances, Both Real and Imaginary

It’s not easy to keep a small ballet company – particularly one that is dedicated to the unglamorous art of reviving neglected chamber works – afloat in today’s ever-shallower cultural waters. But New York Theatre Ballet, founded in 1978 by Diana Byer, soldiers on, despite meager budgets and various setbacks, the latest of which is its impending eviction from the parish house which has served as its headquarters for three decades. (It goes without saying that the charmingly ramshackle brick pile will be torn down and replaced by high-rise condos. Another eccentric feature of the New York landscape bites the dust.)

© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

True, there can be something relentlessly modest about the company’s performances, which are often set to canned music and take place in the rather drab setting of the Alliance Française’s Florence Gould Hall. The dancers are not, for the most part, big personalities, nor will they blow you away with their technique. The company embraces the turn-of-the-20th-century Cecchetti Method, more concerned with anatomic integrity than with razzle-dazzle. (Cecchetti’s motto is “purity of line, simplicity of style.” You get the idea.)

But such seriousness can pay off, as it did this week in a program of new works. What impressed most was the care with which the pieces were chosen, and how well they suited the company. With one exception, they avoided trendiness and facile contemporary clichés like expressionistic lighting and overwrought partnering. Instead, they relied on old-fashioned dance values, the creation of a mood or development of a theme, and musical responsiveness. Importantly, almost all the music was played live. There were three different pianists – Lynn Crigler, Michael Scales, and Allen Shawn – all excellent, as well as a double bassist (Lindsey Horner) and a violinist (Chloé Kiffer). It made all the difference.

© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

The best works of the evening were Light Flooding Into Darkened Room and Short Memory, made respectively by the British modern-dance choreographer Richard Alston and the New York-based ballet experimentalist Pam Tanowitz. Both are intimate and small in scale, intelligent miniatures. Short Memory, which is set to wonderfully loopy music by the West-Coast composers Lou Harrison and Henry Cowell, reveals a subtle humor that extends to the sporty costumes (by the resident designer Sylvia Taalsohn Nolan), complete with brightly-colored toe-shoes that catch the eye with each flick or flexed-footed turn. The ballet is a kind of hyper-formal deconstruction of ballet class, rather in the spirit of Mark Morris (even the musical choices echo Morris’s taste). Short Memory affectionately pokes fun at the formality of ballet. The dancers start simply, with little tendus and arm exercises, gradually layering on odd juxtapositions, bent legs and tilted poses, all performed with a kind of deadpan precision. Meanwhile, the pianist bangs out tone clusters or, in the case of Cowell’s “Aeolian Harp,” leans over and strums the instrument’s innards. (The feeble tinkling produced by the enormous instrument is both funny and strangely touching.)

© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

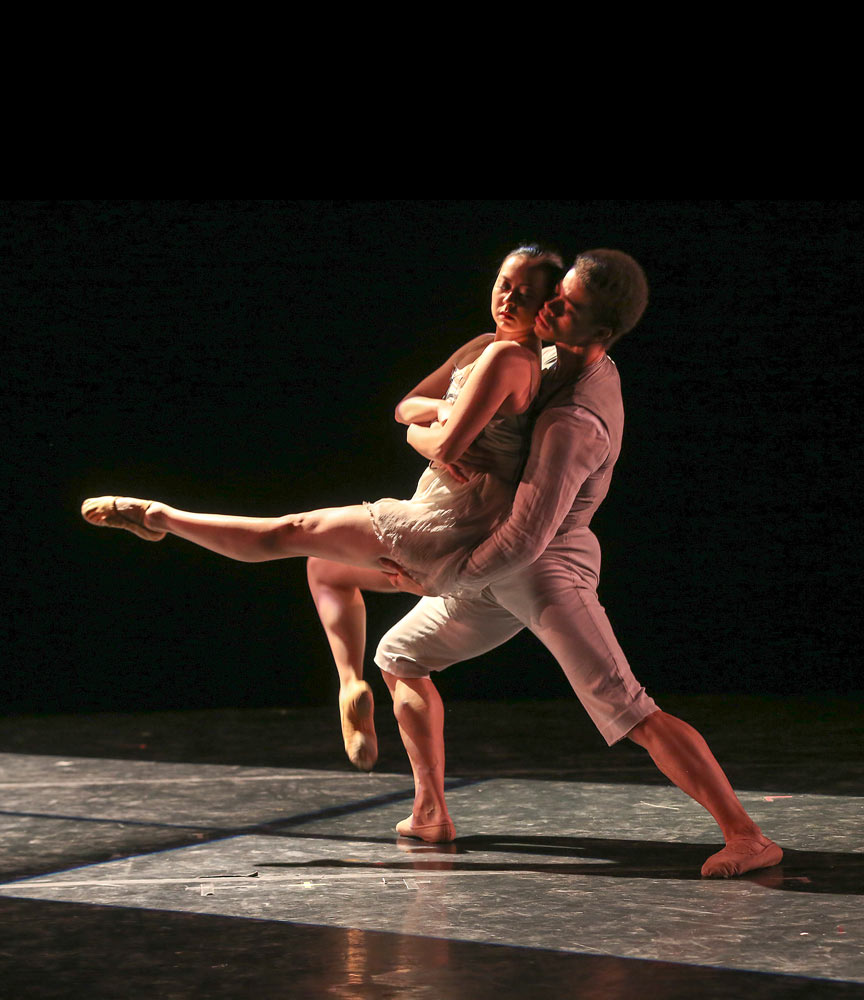

In contrast, Alston’s Light Flooding Into Darkened Rooms, originally created in 1997, is a study in spareness and mood. Everything about it is deliberate, tense. Two dancers, Rie Ogura and the excellent Steven Melendez, enact a private drama on a darkened stage illuminated by a rectangle of crepuscular light, as if from a window. They wear vaguely seventeenth-century attire. The relationship between them is tinged with despair, as if the two had recently experienced a terrible loss. They seem barely able to look at each other or provide comfort, though they often hold hands like man and wife. But aggression lies close to the surface, as when the man pushes the woman into a lurching jump, with some brusqueness. More than once, he slumps to the ground, whereupon the woman uses him to push off into her own terse soliloquies. The first two sections are set to melancholy seventeenth-century lute music by Denis Gaultier; the last, to a kind of deconstructed lute piece by the Japanese mid-twentieth-century composer Jo Kondo. In this passage, the dancers’ interactions become more abstract and disconnected, less pregnant with meaning. They seem to occur in a place beyond emotion.

© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

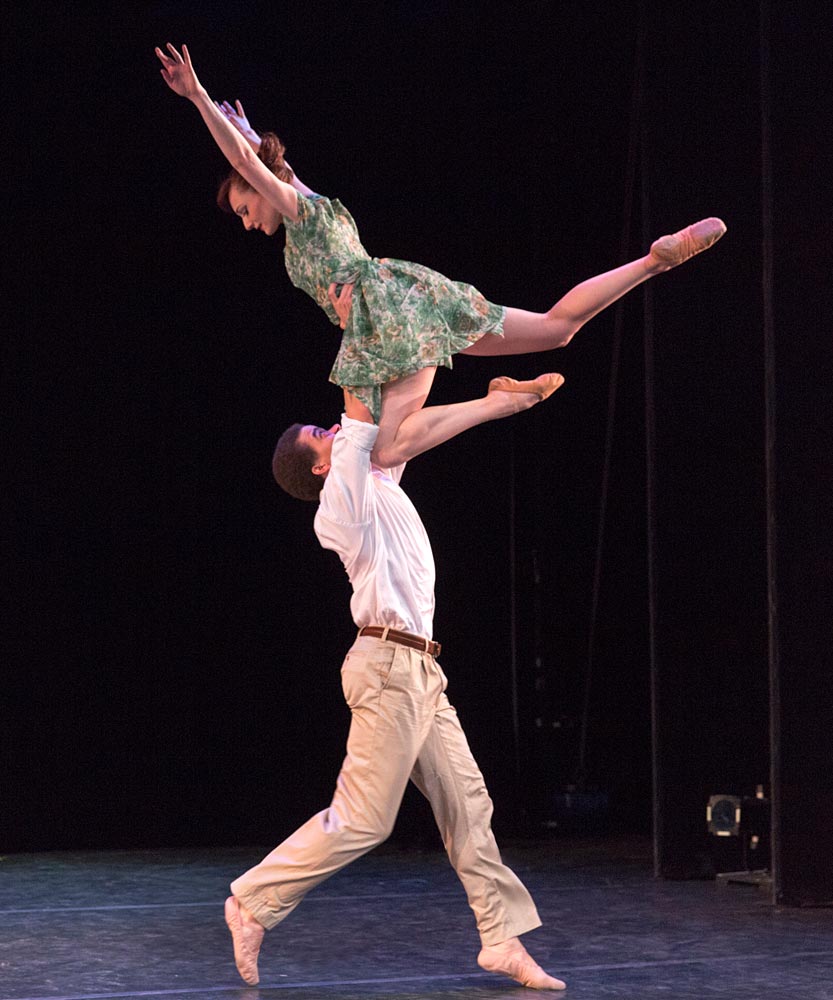

Besides Melendez the company has no “stars,” but the dancers use their bodies expressively, with a welcome plushness in the shoulders and torso, and sensitive arms. (As well as extremely quiet footwork.) Even though none of the other works were on the level of Light Flooding into Darkened Rooms or Short Memory, they were well-conceived for the company. Three Shades of Blue is a charming suite of early twentieth-century popular dances juxtaposed with balletic corps work. Elena Zahlmann radiated quiet sensuality as she danced a soft-shoe, a one-step, and a waltz. Run Loose, by Gemma Bond, a member of American Ballet Theatre, is a short pas de deux, bubbly and peppered with sharp jumps. Jazz, another pas de deux, by Antonia Franceschi, tries a little too hard to look spontaneous. Libera!, by Marco Pelle, has the opposite problem. The pas de deux is weighed down by a kind of reverent religiosity imposed in part by the choice of Bruckner’s Ave Maria (played on tape), but also by the dramatic chiaroscuro lighting and the dancers’ flesh-colored leotards. The choreography included the suggestion of a crucifixion, and many angst-laden lifts. This kind of heavy-handed duet has become a cliché of contemporary ballet; it felt out of character with the rest of the program.

© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

The evening’s wittiest moment contained no dancing or music at all: The London-born dance historian and critic David Vaughan gave a completely delightful recitation of Remy Charlip’s Ten Imaginary Dances, a series of whimsical sketches for non-existent ballets. Charlip was one of the founding members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (where Vaughan worked as an archivist for half a century) and later became a choreographer and children’s book writer. He was much loved by his fellow-dancers, and based on these sketches one can see why. Their surreality and gentleness reminded me of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Each sketch describes a possible ballet. In number nine, “conceived for the Royal Ballet,” a dancer is swallowed by a python but continues to beat his feet together in an entrechat six, entrechat huit, entrechat dix, like a horizontal Nijinsky. Vaughan’s delivery was deliciously dry, leisurely enough to allow each image to imprint itself in one’s mind for a moment before moving on to the next one.

© Richard Termine. (Click image for larger version)

Against all odds, New York Theatre Ballet seems to have thrown off its dutiful air and rediscovered a sense of purpose and fun. This small, valiant ensemble deserves to survive and prosper.

You must be logged in to post a comment.