© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Boston Ballet

Program B: Symphony in Three Movements, L’Apres-Midi d’un Faune, Plan to B, Bella Figura

New York, David H. Koch Theater

28 June (matinée) 2014

www.bostonballet.org

www.davidhkochtheater.com

Boston Proud

In a recent conversation with Robert Johnson of the Star-Ledger, the artistic director of Boston Ballet, Mikko Nissinen, said that one of his aims, now that the company has turned fifty, is to tour more extensively. The troupe’s visit to New York, part of its anniversary year, is its first since 1983. On the evidence of these performances it’s clear that the dancers are more than ready to be seen on an international stage.

Like San Francisco Ballet, where Nissinen danced for ten years, it’s a company that prides itself on the range and eclecticism of its repertoire. Earlier in the week it performed a program of works by William Forsythe, José Martínez – a former Paris Opéra étoile who now directs Compañía Nacional de Danza – and the Swedish trickster Alexander Ekman. Today’s fare proved a more balanced meal, opening with some Balanchine (Symphony in Three Movements), followed by an early Ballets-Russes experiment (Nijinsky’s L’Après Midi d’un Faune) and one of Jorma Elo’s high-speed capers (Plan to B). The closer, Bella Figura, was by the Czech choreographer Jiri Kylian.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

The dancers were impressive throughout, both as a group and individually. Erica Cornejo – sister of Herman, of ABT – caught the eye as the lead nymph in Après Midi, mainly because she slipped so naturally into Nijinsky’s flat, angular and self-consciously archaic movement, inspired by Ancient Greek and Egyptian painting. Cornejo approached the work as a ballet, not an artifact, with an ear to Debussy’s diaphanous, pan-pipe palette. Altan Dugaraa was a slight, innocent, almost too-delicate Faun, without quite enough erotic allure. We have Nijinsky to thank for the introduction of the silent scream into ballet, now an overused effect very much in evidence in Bella Figura.

There was nothing delicate or over-refined about the company’s rendition of Symphony in Three Movements (1972), however. The ballet looked newly-scrubbed, as brassy and defiant as Stravinsky’s 1945 symphony, vibrantly played by the company’s orchestra under the baton of Maestro Jonathan McPhee. Boston Ballet has the attack, the accented and syncopated footwork and the style to pull off this large-scale and hyper-sophisticated work, in which battalions of dancers invade the stage as if ready to do battle. (Even though the ballet was made in 1972, the aggressive tone of Stravinsky’s wartime symphony finds its way into the choreography.) In complete contrast, the central movement, a pas de deux, is a kind of Orientalist fantasy, in which the dancers intertwine with Balinese curled fingers, deep squats, turned in knees. Kathleen Breen Combes and John Lam brought a sense of wonder and surprise to a duet that has become perhaps overly familiar at New York City Ballet. There is a moment in which the two stand, one in front of the other, swimming with their arms and staring out into the darkness. The moment struck me as it hadn’t before – they seemed to be swimming in space, peering into the uncertain future.

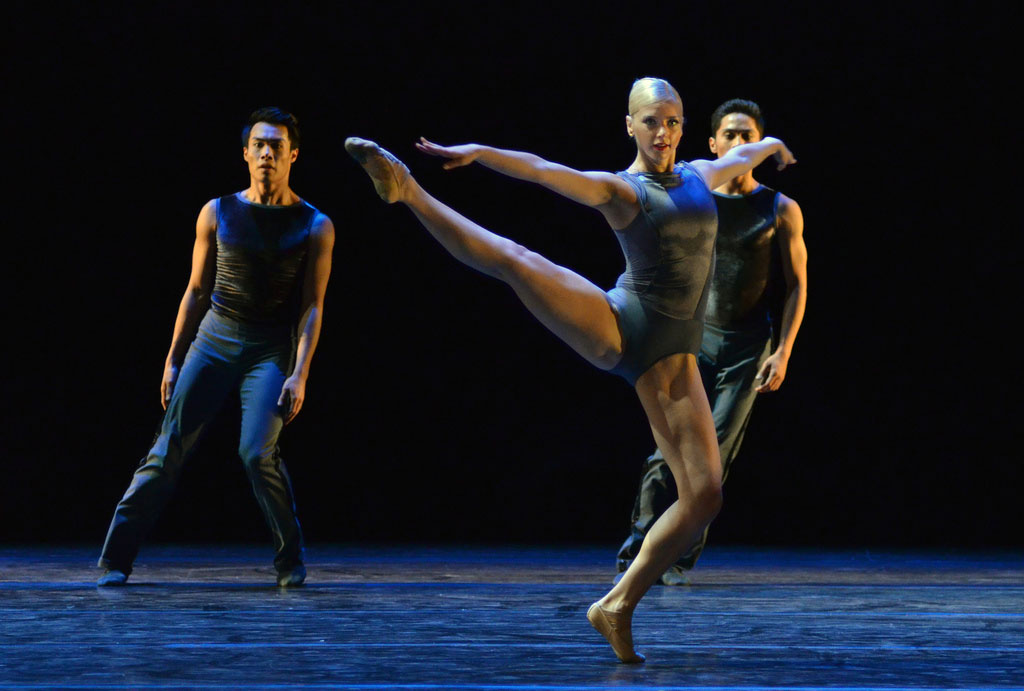

There was a time when the Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo seemed to be tirelessly churning out his futuristic, hyperactive ballets for every ballet company in America, but his real home, since 2005, has been Boston Ballet (where he is choreographer in residence). Plan to B, set to various movements from Heinrich von Biber’s virtuosic violin concerti, is a relatively early work (from 2004), more streamlined and less twitchy than some of the later creations. The dancers move at blinding speed, flinging each other into the air, sliding or pushing at each other’s arms, knees, hips, head – whatever body part is within reach. Elo likes things fast, sharp and clean, and the dancers – particularly the Amazonian powerhouse Whitney Jensen – oblige. Apparently there were no violin virtuosos to hand, so recorded music was used.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

A recording also accompanied Kylian’s Bella Figura, a work made for the Nederlands Dans Theater in 1995. The mood is solemn, the colors dark. In the final section two braziers burn at the back of the stage. If there is a theme, it’s death, or eternity, or the absurdity of life. Curtains – opening, closing, rising, falling – figure prominently. At the start, two naked bodies (mannequins, I presume) are suspended above the stage in translucent caskets. A woman (Rie Ichikawa), topless, finds herself trapped in a black drape, released, trapped again. She emits a silent scream, then several more (see above, Nijinksy). In one passage, a man walks beside a crawling women; after a little while, they switch places. Later, the dancers (men and women) put on voluminous red skirts, undulate their bare torsos, and sway their hips like hula dancers. A chorus intones Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater – the work is set to a collage of familiar Baroque vocal and orchestral music. It is implied that these images, sounds and actions are pregnant with meaning, but mostly they comes across as clichéd, heavy-handed. The Czech-born Kylian invented this particular blend of mood-setting atmospherics, poetic logic and push-and-pull choreography. It has long since been absorbed and imitated by scores of other choreographers.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

This, of course, is the downside of eclecticism. New today, corny tomorrow. Luckily, the dancers seem able to handle whatever comes their way. It’s a quality that will serve them well in their travels.

You must be logged in to post a comment.