© Andre Cornellier. (Click image for larger version)

Louise Lecavalier

So Blue

London, Queen Elizabeth Hall

2 July 2014

www.louiselecavalier.com

www.southbankcentre.co.uk

From the 1980s through the 1990s, Louise Lecavalier used to hit the stage rolling. She’d hurl herself horizontally through the air, peroxided dreadlocks flying, and crash land via someone else’s body. The diva of Edouard Lock’s La La La Human Steps company for some 18 years, she resembled a demented Afghan hound. Now 55, she’s more of a terrier, hair shorn, still tirelessly on the attack.

© Massimo Chiaradia. (Click image for larger version)

After performing with David Bowie and Frank Zappa, she collaborated with a number of choreographers (including Nigel Charnock) and launched her own company before making her first work, So Blue, in 2012. What starts out as a long solo turns into a duet with Frédéric Tavernini, a burly, bearded former ballet dancer – a labrador to her Jack Russell.

The 55-minute piece proceeds as a series of scenes, mostly to dark, percussive music by Turkish composer Mercan Dede. How much his Mediterranean influences inspired her choreography would be hard to determine: she’s always whirled like a dervish, twizzled on tiptoe like a Greek folk dancer. She is a speed freak who looks as though she’s high on amphetamines, head shaking, hands spinning, muttering to herself. Yet each sequence in So Blue, clearly based initally on improvisation, is tightly controlled, insistently repetitive.

Though she stated in her programme note and interviews that she set out to explore what her body would do spontaneously, she doesn’t come up with the unpredictable articulations that William Forsythe or Wayne McGregor have developed. She remains co-ordinated, never really surprising herself even when scrabbling on hands and knees, feet running in place. When she upends herself in a protracted headstand, it is to take a rest in slow motion, legs suspended as though in water. Then the next section is all about arms, as she gazes upwards.

If there’s a linking rationale between the sequences, other than one of physical contrasts, it’s not evident. Lecavalier cannot fail to be riveting because of her compelling presence, as androgynous as David Bowie, as vulnerable as Wendy Houstoun. She needs more variety, however, both in her choreography and presentation: more interesting lighting would help, in the way that Michael Hulls, for example, illumines solo performers. Turning the stage blue half-way through appears perfunctory, as do separate squares of light when Tavernini finally joins in.

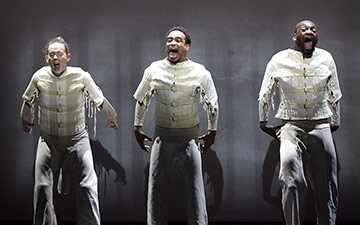

© Andre Cornellier. (Click image for larger version)

He remains an enigmatic figure, moving fluidly to his own inner rhythms. There seems no connection between them until they suddenly embark on what looks like contact improvisation – though the intricate timing is evidently practised. He catches, drags, spins her; then she does the same to him. He bows down so that she can balance along his back as he crawls (disconcertingly to a Japanese song from Kill Bill). She becomes a rag doll in his arms for some expert manhandling until he patiently implies he won’t play any more and they sit, renegotiating, as darkness falls.

© Andre Cornellier. (Click image for larger version)

There’s no accounting for their relationship, no dramatic logic for the way So Blue evolves. It still looks like a workshop piece in which Lecavalier has doggedly tried out basic routines in her attempt to discover her own physical language. Some are based on dancers’ exercises, others on roles in her extensive repertoire. Aware that she can no longer be as reckless as she was, she has yet to develop the choreographic sophistication, not just the physical stamina, to sustain a nearly hour-long show. Her well-earned reputation, though, as a fascinating performer will continue to serve her as she finds her way.

You must be logged in to post a comment.