© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance

21 Feb: Sunset, Death and the Damsel, Brandenburgs

22 Feb 22 matinée: Company B, Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor (Limon Dance Company), Piazzolla Caldera

New York, David H. Koch Theater

21, 22 February 2015

www.ptamd.org

limon.org

davidhkochtheater.com

See the Music, Hear the Dance

The Paul Taylor Dance Company, rechristened Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance, is in the midst of its yearly three-week New York run at the Koch Theater. This is a pivotal time for the company. Given Mr. Taylor’s advanced age, it has decided to plan for the future by beginning to widen its repertory to include the work of other choreographers. This season there are two “outsiders” in the mix: Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, from 1938, danced by the Limón Dance Company, and Shen Wei’s Rite of Spring (2005), performed by Shen Wei Dance Arts. For next year, Taylor has commissioned three new pieces for his own dancers. The choreographers in question are Doug Elkins, Larry Keigwin, and Lila York.

The other big change is the decision to have live music whenever appropriate. At the Koch this season, the house band is the Orchestra of St. Luke’s under the baton of Donald York. In principle, live music is a very good thing, but so far the effect has sometimes been marred by lackluster performances – Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos were a particularly tough slog, musically speaking – and a somewhat loose musicality onstage. Not surprisingly after so many years of dancing to taped music, the dancers look more assured when moving to familiar recordings, as they did in Company B and Piazzolla Caldera at the March 22 matinée. Too, the live music has a pesky way of emphasizing times when Taylor’s choreography itself seems to almost ignore the score or ride roughshod over it with vigorous, strenuous combinations of steps.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

The March 21st evening performance opened with Sunset, which seemed to swim in the warm glow of Elgar’s Serenade for Strings and Elegy for Strings. It is a remarkable work, one of Taylor’s most evocative and subtle. (It would be even more so if the female dancers didn’t smile quite so brightly.) A group of male soldiers gathers, perhaps on the eve of deployment, and flirts with an equal number of girls in light summer dresses. Two soldiers engage in horseplay, teasing each other with gruffness mingled with tenderness. One places a hand on the other’s shoulder, Paul Taylor’s universal sign of mutual understanding. Here, the gesture suggests an intimacy born out of fear of the unknown – perhaps one of them will be dead tomorrow? Michael Novak, a dancer with a particularly innocent manner – still somewhat underused in the company – has a winsome solo in which he shows off, bashfully, for one of the girls (Parisa Khobdeh), only to get carted off by his friends. But the heart of the piece is a section set only to the sound of birdcalls, a dream sequence in which the women tend to the men, nursing injuries, like angels of mercy.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

As usual, there are two new works by Taylor. One is Death and the Damsel, set to a sonata for piano and cello by Bohuslav Martinu. The only thing the music and the dance have in common is a macabre sensibility; for the rest, the dance seems to practically ignore the music, focusing instead on the cartoon-like torments visited upon a young girl. This innocent waif (a sprightly and graceful Jamie Rae Walker) awakes in her New York garret apartment only to be dragged off to a ghastly “dance club” – identified as such by the drop curtain, designed by Santo Loquasto – and raped by a series of louche denizens of the night wearing shiny black S&M gear. There’s no confusing what is going on: the men squat on her chest as she lies on the ground, facing away from the audience, and yank open her legs in a wide “V” while staring insistently at her crotch (what is it about Taylor and crotches?). Because of her position, the audience is forced to stare at it too, for quite a long time. Each of her tormentors yanks her up her into the air, flips her over, and passes her on to the next guy.

Finally, in the third section, the young girl fights back, overcoming one of her vampiric attackers, played with almost tongue-in-cheek hatefulness by Laura Halzack. She appears to get the upper hand, only to be once again engulfed by the coven of marauders. (I hear that on another night the dance ended differently, with Walker returned safely to her bed.) The brutishness of human behavior is not a new topic for Taylor – just think of Big Bertha – but it seems wholly gratuitous here, too arbitrary and pointless to be shocking. Beware nightclubs!

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

The evening closed with Brandenburgs, which, after a rough start, managed to transcend the muddy playing of the orchestra. The dance contains one of Taylor’s “god solos,” in which an Apollonian male figure, usually bare-chested, stretches, tilts and unfolds to fill the space around him, a celebration of the body’s balance and musculature. It was danced, as these solos so often are these days, by Michael Trusnovec, a dancer with beautiful proportions and complete dominion over every inch of his body. Slowly, deliberately, he moulded himself into heroic, three-dimensional shapes that seemed to coil around themselves, without a beginning or an end. There are hints of Balanchine’s Apollo in Brandenburgs, mainly in a section in which our hero dances with three women, pulling them into a daisy chain, lifting them with the crook of his elbow. After which, the other men arrive, tearing across the stage in diagonals of hops, split leaps, gallops. This crescendo of exploding lines creates a sense of elation, much like the end of Esplanade.

At the March 22 matinée, the company gave a strong performance of the World War II period piece Company B. The tall, refined, and proudly redheaded Heather McGinley was especially touching as the young bride in “There Will Never be Another You,” dancing a lonesome duet with a man already as absent as a ghost (he never looks at her). This was followed by Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia and Fugue, performed by the Limón company and accompanied on the organ by Kent Tritle, director of cathedral music and organist at St. John the Divine. It’s a stately work, noble, architectural and pleasing to the eye. The Limón dancers moved with dignified deliberateness on a three-tiered platform, gradually spilling out across the stage in clean walking patterns, falls, stately pendular movements of the legs and sculptural poses. Kristen Foote was the leader of this heroic band, her face turned toward the heavens, movements composed, expansive and clean. One can imagine Taylor, once a dancer in Humphrey’s company, chafing at so much nobility of spirit – not his style – but there is no denying the elegant simplicity and musicality of the work.

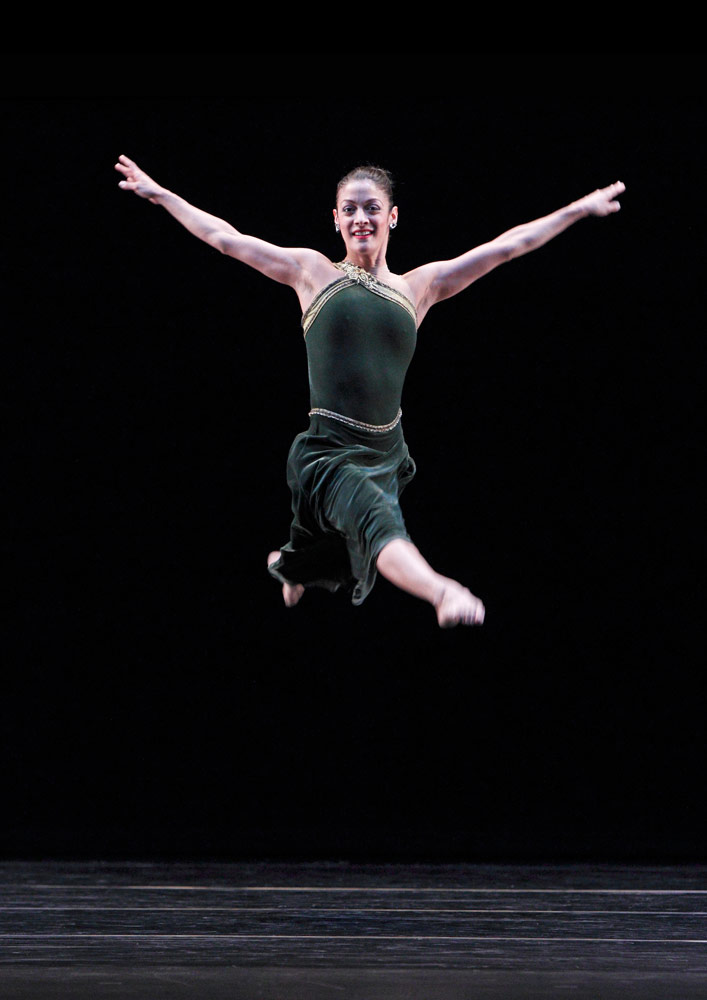

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

All of which was quickly wiped away by the closing work, Taylor’s ode to sexual longing from 1997, Piazzolla Caldera. As we well know, tango equals sex, and this is the piece’s stock-in-trade – not a particularly original concept, but effective enough. The men pose suggestively, hips forward and shirts unbuttoned to the waist (costumes, once again, by Santo Loquasto). The women, in short dresses that reveal thigh-high stockings and garters and black bras, respond with exaggerated come-hither looks and open-legged squats. Behind this brassy façade there are moments that suggest something more interesting, the eroticism and shifting alliances of a ménage a trois (sensually danced by Parisa Khobdeh, Eran Bugge, and Robert Kleinendorst), the tired acquiescence of a foursome. A drunken male duet that vacillates between coupling and combat.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

This duet, danced by Francisco Graciano and Michael Apuzzo, demands impressive virtuosity, as when one man balances the other on his chest while bending back all the way to the floor. For a moment, you’re afraid he might just collapse beneath the weight, or his back might break. But then, almost all Taylor’s high-intensity choreography requires a Herculanean level of effort. One can’t help but marvel at the dancers’ stamina over the course of an evening. How do they survive night after night? They are some of the hardest-working dancers in the business, and they have the muscles to prove it. Sometimes, as in the “Bugle Boy” solo in Company B, Taylor seems bent on killing them through sheer exhaustion. It is this this effort, even more than live music or new commissions or off-putting sexual politics, that lies at the heart of the Paul Taylor experience.

You must be logged in to post a comment.