© Whitney Browne. (Click image for larger version)

Paul Taylor Dance Company

Brandenburgs, Rewilding, Cascade

★★★★✰

New York, Neidorff-Karpati Hall

12 June 2019

www.ptamd.org

www.oslmusic.org

Paul Taylor Does Bach

This is a period of transition at the Paul Taylor Dance Company. Taylor died last summer, at the venerable age of 88. The company already had a succession plan in place, with the dancer Michael Novak designated as the next artistic director. More recently, the ensemble announced that it will be losing six longtime dancers, a substantial number. (There are currently 20.) This week, they are peforming in Orchestra of St. Luke’s Bach Festival at the Manhattan School of Music. Inevitably, it feels like a farewell, both to a group of dancers, and to an era.

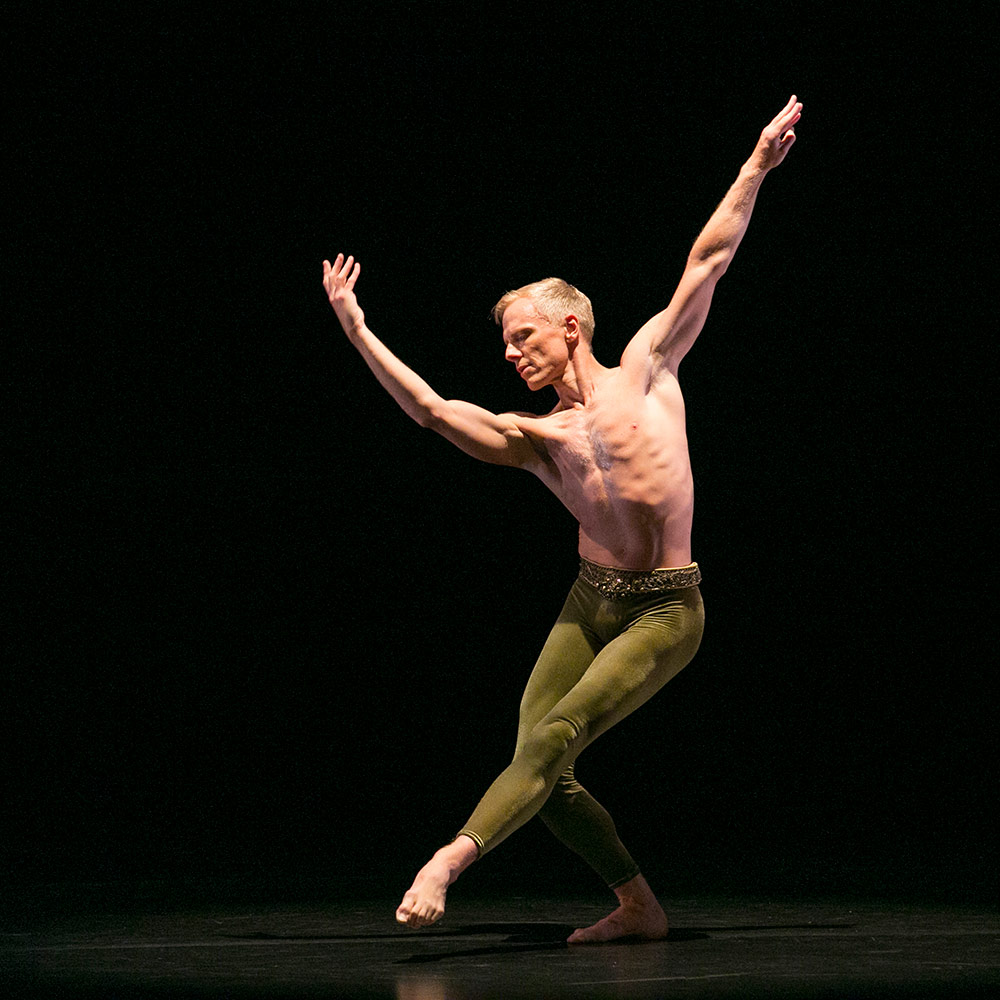

Most of the faces onstage are familiar, which makes the fact of their imminent absence all the more palpable. This is particularly true in the case of Laura Halzack and Michael Trusnovec, two pillars of the repertory, frequently paired together. It’s difficult to imagine the company without Trusnovec, a dancer of Apollonian gravitas and purity. Over the years, he has honed his movement almost to pure essence, arriving at an amazing economy of means; equally impressive is the amazing weight and presence of his stillness. Each time he walks onstage, in that slow, pantherine way he has, the air changes. In a long list of Taylor works he is the still point, the cool, benevolent center around which everything rotates. There is no other male dancer in the company with these qualities.

© Whitney Browne. (Click image for larger version)

They were particularly apparent in the male solo of the opening piece, Brandenburgs (1988), set to movements from two Brandenburg Concerti. As Trusnovec entered the spotlight he became the Vitruvian Man, measuring and defining the space around him. With total command, he curved and straightened, tilted and reached far into space, deploying that amazing back that is one of the great attributes of the Taylor dancers. Taylor himself was a swimmer, with a long, supple, muscular back.

This came after a section in which he had danced with three women, Eran Bugge, Laura Halzack, and Christina Lynch Markham, who circled and linked arms around him in an almost Balanchine-esque manner. He offered his hand to each; they bowed and launched into their solos, performing for his pleasure and approval. Bugge, who is dancing with even more abandon and sensuality than usual, played a cat-and-mouse game, mostly with her eyes and hips. It was one of the high points of the evening, which also included the 1999 Cascade and a new work, Rewilding, by the Canadian choreographer Margie Gilllis. The festival comprises all six of Taylor’s Bach pieces, as well as two by guest choreographers.

Musically, however, it was the weakest link – the Orchestra of St. Luke’s sounded woefully out of tune, as well as muffled. Thankfully, the playing improved over the course of the evening.

Gillis’s Rewilding, set to orchestrated selections from The Art of the Fugue, picks up on a few of Taylor’s themes: the communal spirit, gentleness of touch and simplicity of vocabulary. But where Taylor undergirds that vocabulary with a steely sense of structure and order, Gillis allows it to meander and flow, leaving certain sections looking undercooked. Her program note refers to a need to “reintegrate with our wildness.” This may explain the improvised, un-focused feeling of the opening sections: lots of running and collapsing. As the piece proceeds it becomes more focused, particularly in a series of solos. Alex Clayton stood out here, cutting and folding the air rhythmically with his arms and torso. The solo was made of contrasts: sharp and soft, fast and slow. At the moment, Clayton is the most explosive Taylor dancer, the one with the sharpest edges, a welcome exception to the rounded Taylor esthetic.

© Whitney Browne. (Click image for larger version)

Cascade, similar in spirit to Brandenburgs but more classically inclined – and performed in silly pseudo-medieval costumes by Santo Loquasto – was danced with less clarity than the other two works, perhaps in part because it contains quite a bit of tricky partnering. The main sticking point was a recurring lift in which the men held the women overhead in arabesque. The small size of the stage didn’t help – at times, the dancers looked constricted, particularly when entering or leaving the stage. Cascade suffers, too, from the over-familiarity of some of the music, particularly the Largo from Bach’s Fifth Concerto, for piano and pizzicato strings. A favorite of wedding processions – it’s almost a cliché.

One can only wish the Paul Taylor Company well in this period of change. The dancers, new and old, perform with a warmth and openness – toward each other and toward the audience – that is rare. The humanity of the Taylor esthetic is one of its most appealing features. The dancers dance their hearts out, for each other, and for you. May this never change.

Thank you for this wonderful review. I didn’t see the performance but almost feel as if I had. Your description of Trusnovec’s qualities pinpoints what I love about him. I’ve watched the Taylor company for many years and Trusnovec is truly one of the greatest.

Many thanks, Marta. A very unique and special dancer.