© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Raven Girl, Connectome

London, Royal Opera House

6 October 2015

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

Edward Watson returned soon after receiving his MBE at Buckingham Palace to dance in the Royal Ballet’s latest double bill, exchanging his suit for a postman’s uniform, followed by skimpy white underwear. For him, October 6th must have been a day and night to remember.

In this revival of Wayne McGregor’s Raven Girl, Watson becomes something more than a postman: he’s the writer of the story we are about to see (whose author is actually Audrey Niffenegger). In the opening scene, he takes up a quill and scribbles in a book, inspired by shadowy visions of birds. In the final scene, he decides the ending is too sad, tears up the book and writes a happy-ever-after conclusion.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

As a would-be gothic novelist, Postman Watson now has a long solo to express his frustrations, instead of simply circling the stage on his bicycle. He wants to be a creator, not just a deliverer of letters, and he longs to fly – cue long arms and yearning arabesques in a mash-up of ballet and contemporary dance agonisings. Watson is such a compelling performer that he turns the choreographic gibberish into a convincing characterisation.

Off he sets on his bike to deliver a letter to a mysterious cliff-face. He rescues a fallen raven nestling, marries her and they have an egg together. Olivia Cowley as the raven bride conveys her avian otherness, hampered though she is by a mask and tabard of feathers. Sarah Lamb as the product of the egg is a different kind of alien – a disturbed girl who wants to fly. She is haunted by a corps de ballet of Hitchcockian birds that flail around the stage to eerie music (by film composer Gabriel Yared).

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

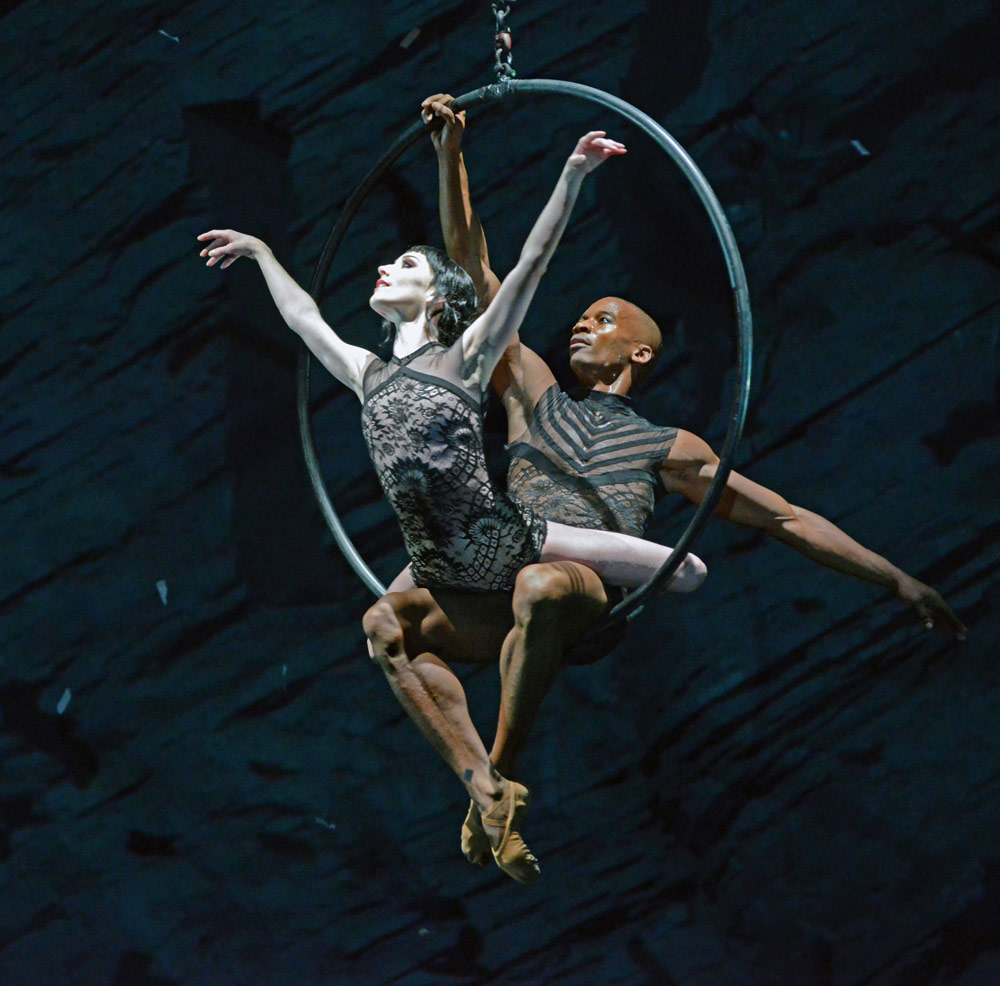

Lamb doesn’t do clumsy, so her efforts at flying have none of the awkwardness of unfledged nestlings. She’s poignant and even poetic when she swirls weightlessly in a suspended hoop, a beautiful image. The corps of ravens who remain on the ground flock together unimaginatively in repeated triplet runs, waving plume-like banners. Since they are mythical creatures, perhaps it doesn’t matter that they don’t resemble birds in flight. Ravi Deepres’s film animations of flapping shadows are more enticing.

The city dwellers in the town where Raven Girl attends university don’t look much like people either. We’re in an Expressionist nightmare world where the biology lecturer is a Dr Frankenstein (or rather, H.G. Wells’s Dr Moreau) who creates chimeras – hybrid mixtures of animals and human beings. Raven Girl wants to become one of them: in a programme article, Nifenegger makes a comparison with transgender people who feel they were born in the wrong body and who opt to undergo corrective surgery.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013.

Before Raven Girl submits herself to Thiago Soares’s Doctor, she is wooed by Paul Kay’s Boy. He has the best-constructed, most balletic solo in the ballet, expressing his excited interest in the elusive girl while being too bashful to approach her except through the offer of a paper bird. Kay no longer looks as boyish as he did in the premiere two years ago; he’s a mature university student, perhaps.

Raven Girl’s mutilation at the hands of the abusive Doctor is horrific, though her transplanted wings are spectacular. (McGregor’s fascination with prosthetics dates back to his Nemesis for Random Dance in 2001.) She has been transformed into an Icarus who can’t fly, however elegantly she unfurls her pinions or balances on pointe. Broken-hearted, she collapses over the dead body of the surgeon, who has been killed by the distraught Boy.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version

Her father seizes a magic feather and writes an ecstatic apotheosis for his daughter and a fairy tale prince (Eric Underwood). No longer encumbered by prosthetic wings, Lamb appears as featherweight as a bird, her legs soaring upwards as Underwood supports her manfully (or ravenly). Both are finally transported by the circular swing as feathers flutter from the heavens.

Like Niffenegger’s graphic novella that illustrates the ballet, Raven Girl is a series of tableaux without much explanation or motivation. The performers try to flesh out their characters, though only three are human beings: postman father, would-be boyfriend and mad doctor. The raven-maiden is an enigma, more conflicted than swan-maiden Odette. As with all recently invented myths, it’s hard to care about the outcome or to discern any moral, other than don’t undergo trans-species surgery. Though some of the visual effects are stunning, some are lost to areas of the auditorium with restricted sightlines. Another theatre might suit Raven Girl better – Sadler’s Wells, perhaps.

Alastair Marriott’s Connectome was last seen in May 2014, with Natalia Osipova in the sole female role, now taken by Lauren Cuthbertson. The title refers to a wiring diagram of the neural connections in the brain, unique to each individual. Dedicated to Marriott’s late father, Connectome is a requiem set to four pieces of music by Arvo Part. Inevitably, it has echoes of Kenneth MacMillan’s Requiem and Song of the Earth, in its farewells to life.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Es Devlin’s set of shimmering silver rods gives way to Luke Halls’s video imagery of intricate neural pathways. Initially, the female protagonist makes her way through the thicket of rods to find – or remember – two men important to her: Steven McRae and Edward Watson. Four other men, Luca Acri, Matthew Ball, Tomas Mock and Marcelino Sambe represent other friends and angelic spirits.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

With McRae, Cuthbertson recalls tender young love in a duet that becomes a pas de trois with Watson, both supporting her in lifts. The four young men, seated in the profile pose, one leg raised over the other, that occurs in Ashton’s Scènes de ballet, serve as a kind of backing group. McRae, their leader in a sequence to Part’s setting of ‘Our Father’ (sung by a boy treble), dies in their midst, sinking into the circle they form.

Watson offers consolation in a hyper-supple pas de deux to yearning strings. Cuthbertson wraps herself around him acrobatically but he too departs and leaves her alone. There’s a death-defying finale, however, in which the two leading men return to leap and dart with Cuthbertson and the others. The projected network of connecting white lines turns technicolour as it completes the leading character’s connectome. It vanishes when she’s alone once more, extinguished in a backbend in darkness.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Although Cuthbertson doesn’t have Osipova’s athleticism, she brings a nuanced musicality to the phrasing of Marriott’s choreography. He is adept at the linking steps that McGregor ignores in his non-narrative creations for the Royal Ballet, though the pas de deux with Watson looks much like one of his. Marriott’s inventions for the group of young men show off their agility admirably. In the end, though, Connectome is memorable mainly for its striking designs.

You must be logged in to post a comment.